Blurring the Interspecies Divide: Eeb Allay Ooo! and Multispecies Cohabitation in Anthropocene Delhi

Disclaimer: This essay and my accompanying interview with Prateek Vats reveal crucial plot details about the film.

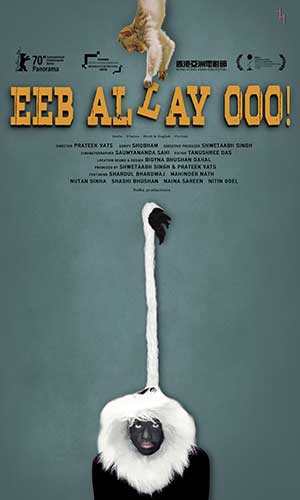

Eeb Allay Ooo! (2019), directed by Prateek Vats, is part of a recent oeuvre of multispecies Indian cinema, both fiction and documentary films, that includes internationally acclaimed titles like Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes (2022), Anirban Dutta and Anupama Srinivasan’s Nocturnes (2024), Jesse Alk’s Pariah Dog (2019), and Amit Datta’s Saatvin Sair (2013). Based on the life experiences of “monkey repellers” (men who try to chase free-ranging rhesus macaques vocalizing the onomatopoeic “eeb allay ooo”), the film narrates the story of Anjani (Shardul Bharadwaj), a migrant who arrives in Delhi to live with his pregnant sister (Nutan Sinha) and brother-in-law (Shashi Bhushan) in a Delhi chawl. Anjani’s brother-in-law, a security guard, procures a job for Anjani as a monkey repeller.

The narrative core of the film is the friendship that develops between Anjani and Mahender (Mahender Nath), another monkey repeller who has been in the profession for much longer. Mahender takes Anjani under his wing, and a strong bond develops between them only to be sundered brutally when the former is lynched by a mob for accidentally killing a monkey (monkeys, associated with Hanuman, have a sacral status in many parts of India).

The narrative core of the film is the friendship that develops between Anjani and Mahender (Mahender Nath), another monkey repeller who has been in the profession for much longer. Mahender takes Anjani under his wing, and a strong bond develops between them only to be sundered brutally when the former is lynched by a mob for accidentally killing a monkey (monkeys, associated with Hanuman, have a sacral status in many parts of India).

At one level, Eeb Allay Ooo! is a powerful and poignant exploration of class divides and spatial segregation in neoliberal Delhi. This is accentuated by the repetition of shots that show Anjani and other residents of the chawl crossing the railway tracks to get to their places of employment in the city’s rich and posh areas.

The railway tracks function as a marker of the rigid spatial divides in the unequal city.

The swanky and rich urban enclaves on the other side of the tracks, epitomized by the air-conditioned bubble of the Delhi metro, the wide-open spaces of Raisina Hills (where India’s Parliament House and Rashtrapati Bhavan, the official residence of India’s president, are located), and the broad avenues of South Delhi are contrasted with the crowded alleys and squalor of the chawl that Anjani lives in. The railway tracks function as a marker of the rigid spatial divides in the unequal city. The precarity of the urban laboring class is emphasized strongly by the sudden and unanticipated violent demise of Mahender, and objects circulate through the film, Vats reminds us in our interview, as powerful “Chekhovian” symbols to highlight the uncertainty in the lives of the urban proletariat. Anjani’s brother-in-law’s gun, for instance, functions as a fetish in the film—its presence causes domestic discord and simultaneously illustrates the precarious nature of employment in the city. Anjani’s brother-in-law shies away from violence but must carry this symbol on his person to maintain his precarious employment.

Besides being a subtle yet unsparing critique of neoliberal processes and their attendant devastations, Eeb Allay Ooo! is also a powerful representation of multispecies cohabitation in the Anthropocene. Cohabitation involves both coexistence and violence as we live with animal others in the spheres of the urban quotidian. The free-ranging rhesus macaques, a ubiquitous presence in the city, exist in a situation of mutual violence with the monkey repellers—they are shown aggressively charging Anjani numerous times while the accidental killing of a monkey leads to Mahender’s shocking death. But remarkably tender moments of interspecies contact, such as acts of everyday commensality, are also subtly woven into the narrative.

The film also frequently blurs species divides.

Moreover, the film also frequently blurs species divides. A monkey captured in a cage is counterpointed to a scene where Anjani is bullied by his fellow monkey repellers after he was trapped in the same cage, revealing their shared condition of entrapment and helplessness. But this blurring of the species divide is best illustrated by the contrapuntal positioning of the opening and closing montages of the film. The opening montage shows close-ups of monkey repellers vocalizing “eeb allay ooo.” The closing montage shows the grieving Anjani dressed in his langur (Semnopithecus entellus, also known as the Hanuman langur) costume—men dressed in langur costumes were also employed to scare off monkeys in Delhi—participating in an ecstatic dance at a festival devoted to Hanuman.

The last shot shows a ghost mask alternately hiding and revealing the blackened yet unsettlingly smiling face of Anjani staring straight at the camera. In her essay “Animating Caste,” multispecies ethnographer Yamini Narayanan talks about the violence inherent in the combined processes of the animalization of the human, the humanization of the animal, and the animalization of the animal—her example is the sacralized cow but could easily be extended to the sacral status of the monkey as well. The contrapuntal montages at the opening and the closing of the film accentuate the shared potential for subjecting others and being subjected to violence but also reveals the ethical vision inherent in this haunting exploration of multispecies cohabitation in the neoliberal city.

University of Oklahoma

Read Baishya's interview with Prateek Vats from this same issue.