Reading in Iran: Literature That Crosses Borders

Many years ago, in the old days of dial-up internet, when I was still living in Iran, I would spend time reading book reviews online, making a list, and then passing on that list, via email or phone calls, to whoever would soon be visiting Tehran from the US. In a market closed to the outside world, with no global credit or debit cards, no possibility for online orders, no reliable US–Iran postal services, the only option was to put together a network of friends and family travelers who would purchase and deliver via their suitcases. (One particular book that found its way to me in Tehran was Roberto Bolaño’s Last Evenings on Earth, translated by Chris Andrews, which changed my literary trajectory in many ways. At that time, it had just been released.)

Fast-forward to years ahead, during the 2000s and 2010s. I was living in the US, as an MA and later PhD student, traveling back to Tehran once or twice a year during my academic breaks. Now I would play that role for friends, buying books here and taking them back with me in my suitcase. One friend, a translator and bibliophile who had an expansive personal library, would sometimes send me dozens of Amazon links, for a wide range of books of fiction, nonfiction, and plays, often ordering secondhand for better prices. Many times, it was through his lists that I’d be introduced to authors whose works excited me.

Fast-forward to today. I have not been back to Iran for more than five years. When World Literature Today asked me to write about what Iranians are reading these days and the trends in the literary market, I immediately remembered a video I watched some years ago of a famous Iranian author, of an older generation, who has been living in exile in the US for many years. In part of the conversation, she noted that she continued to closely follow the literary landscape within Iran. Minutes later, someone in the audience asked her opinion about a recent novel by a younger female author in Iran that had gotten a lot of critics’ and the public’s attention. The exiled author said she had not heard about the young author and that book. The reality of that kind of disconnect has terrified me since.

Even today, despite all the access we have—through social media accounts run by a variety of participants in the literary landscape, public groups on platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram, as well as personal groups and one-on-one chats with friends and peers—I am aware that there is still so much that I am missing. Nothing can replace the experience of walking into bookstores, browsing, and chancing upon titles, or being suggested a title by a bookseller who knows you and your literary taste; having in-person meetings with publishers and editors; or sitting around dinner and tea with friends and sharing literary joys and horror stories. What the lived experience offers nothing can. That is why I decided to reach out to a few people on the ground in Tehran and ask them to share with me their observations and insights. The following is what they—a translator and PhD student in anthropology, a journalist/book editor, a bookseller, a translator, and a photographer—sent me.

—poupeh missaghi

Setting the Literary Stage

by Emad Mortazavi

I am a book hoarder—not in my house, but on my Kindle. I’m not rich; I steal books. Well, nothing too confessional here: we are all biblioklepts in Iran. We cannot order books from Amazon due to US sanctions and a whole bunch of other reasons. When you download illegally, tsundoku is inevitable. If you are a bibliomaniac suffering from archive fever, Iran is heaven. My library of Babel—my Kindle—is reserved for novels written in English. For books written in or translated into Persian, I buy hard copies.

I have noticed, on the subway, Gen Z readers listening to audiobooks and following their epic fantasy sagas on e-readers. They follow “book influencers” on Instagram as well as book clubs and reading circles taking place on Google Meet. But for me, a forty-year-old doing his best to keep up with technology, reading the new Persian translation of Middlemarch on Kindle is a no-go.

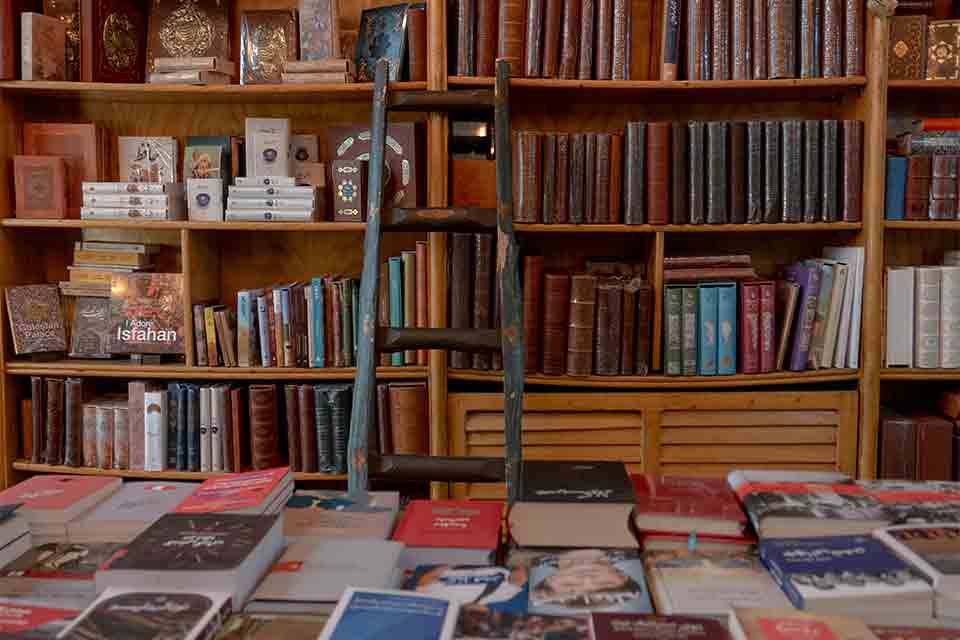

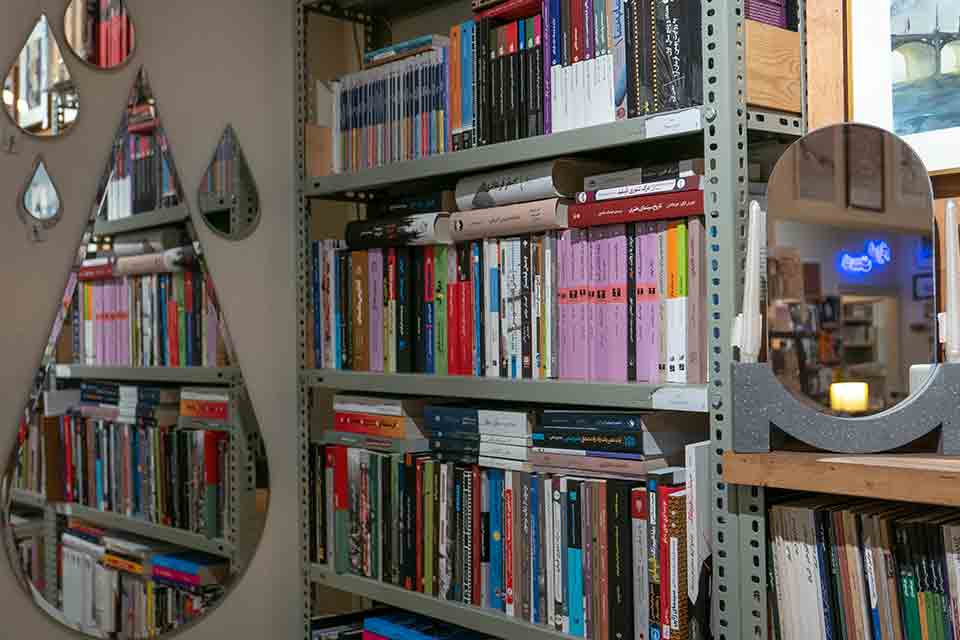

Ordering Persian or translated books online, given the maddening traffic jams of Tehran, is becoming more popular these days. Nevertheless, many bibliophiles still prefer going to an actual bookstore. Huge bookstore chains are replacing small independent ones, but the latter still survive, serving as favorite haunts where you can hang out with writers and translators and enjoy readings and literary events. Picture this: a renovated older apartment with colorful sofas, chill ambient music, bookshelves reaching the ceiling all round you, and a backyard where you can grab a coffee, bum a cigarette, and exchange opinions on the latest work of Annie Ernaux with a random stranger. Yes, such places still exist in Tehran—a space where you know you can meet literary friends without prior notice.

Whether in these cozy independent bookstores or on the Instagram live feeds of book influencers, one buzzword dominates the conversation nowadays: essay. Personal essay, narrative essay, creative nonfiction, and, of course, memoir. These genres have topped Iranian reading lists in recent years. Is this a fleeting fad inspired by the North American literary scene, or is it a deeper historical call from the zeitgeist? Maybe both. When I was new to the world of reading in the 1990s and 2000s, everyone was reading and writing short stories—short-story anthologies were celebrities. In the 2010s, novellas took the stage. Now, in the 2020s, works of nonfiction allure Persian readers.

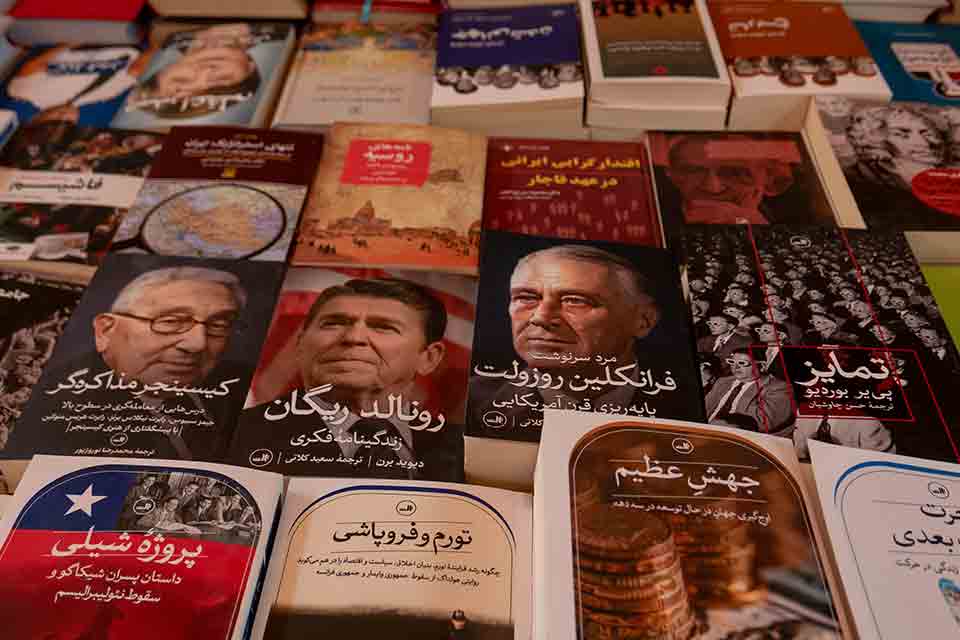

Over the past five years, major publishing houses in Tehran have launched new series dedicated to nonfiction, mainly translations of contemporary anglophone essayists but also works by Persian writers. From the travelogues and memoirs of Qajar women to Afsaneh Najmabadi’s Familial Undercurrents; from letters to epistolary novels; from Rebecca Solnit and Jonathan Franzen to Zadie Smith; from John Berger to Susan Sontag—anyone from the boutique of the New Yorker, dead or alive, will do. Whether monographs, essay collections, or edited volumes centered on themes like death, mourning, motherhood, migration, love, or urban life, the message is clear: there is an open invitation to read and write about lived experiences, daily narratives, and the mundane matters that were long excluded. This exclusion was due in part to government censorship but also to the limited availability of certain literary forms and genres in the Persian literary tradition.

Over recent years, personal perspective and individual lives have gained significance in Iran, and the Woman, Life, Freedom movement has been its greatest social manifestation. The long-suppressed “I” of Iranian women is finding a collective voice and reminding us of the importance of bodily experience and everyday life in contemporary Iran. Readers demand fresh, firsthand, and “real” narratives that speak to their own experiences—hence, the popularity of personal essays.

That being said, for Iranian bibliophiles, fiction is far from dead (I still haven’t finished the second volume of my Middlemarch). While Persian fiction writers tend to focus more on novellas, translated novels still dominate the rankings. The names you’ll see on book covers these days include Julian Barnes, Haruki Murakami, Orhan Pamuk, Magda Szabó, Amélie Nothomb, Emmanuel Carrère, and Kazuo Ishiguro. Every now and then, an easy read also takes over, welcoming young readers who have bid farewell to their fantasy worlds and arrived at new literary fantasies—Fredrik Backman’s A Man Called Ove, Jojo Moyes, and, in the past decade, Steve Toltz’s A Fraction of the Whole, Elif Shafak’s The Forty Rules of Love, and Mitch Albom’s Tuesdays with Morrie.

The classics never truly die in Iran—especially the Russians. Every year, I ask my bookseller friends: What was the bestseller this year? And in the top three, there is always a new translation of a Dostoevsky masterpiece or simply an old translation rediscovered by a younger lover, ready to experience their vital dose of White Nights.

One thing that also never dies in my country is narratives of political struggle. Whenever Iran’s streets witness protests—such as during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom movement—books on totalitarianism take center stage: Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Timothy D. Snyder’s On Tyranny, Ariel Dorfman’s Exorcising Terror, Étienne de La Boétie’s Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, and Václav Havel’s Open Letters.

“Whenever Iran’s streets witness protests—such as during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom movement—books on totalitarianism take center stage.”—Emad Mortazavi

I cannot close without mentioning the importance of women writers in the past years. In Iran, each book’s copyright page lists the number of print runs and copies, making it easy to gauge a book’s popularity over time. And as I’ve observed in recent years, it is women writers who are most celebrated. A quick glance at book covers in any Tehran bookstore reveals a striking trend: women now outnumber men as both writers and translators. A new society is being born, and, of course, the literary scene is the stage in which the change becomes expressive.

The Last Bastions of Social Class

by Leili Entezari

translated by poupeh missaghi

The Iranian book market has long surprised both booksellers and publishers; it seems no one can really understand or predict what is going on in readers’ minds.

If someone were to tell me that one day Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem would sell more than sixty thousand copies in Iran, a number dramatically higher than regular print runs of hundreds or a few thousand, I would say they were joking with me. But this did actually happen when Borj Books published the book, translated into Persian by Zahra Shams, for the first time in 2020. I experienced a similar shock when some four thousand readers recently rushed to purchase Moeen Farrokhi’s 2023 translation of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (Borj Books), or when Poust Sakht [Hard-skinned], a Persian novella by female author Sanaz Asadi sold more than twenty thousand copies for Cheshmeh in just one year. In an economy burdened by one of the worst inflations ever and no positive outlook on the horizon, all this was unpredictable and a complete surprise.

On the one hand, we have the wide popularity of self-help books as well as such translated titles as Matt Haig’s The Midnight Library (with more than two hundred thousand copies sold), memoirs by Matthew Perry and Prince Henry, and translations of many best-selling novels on Amazon’s home page (with many titles having several translations released simultaneously by different publishing houses as a result of the copyright chaos in the Iranian market). On the other hand, we have books sought particularly by college students and the so-called elite middle class. One time, they became so obsessed by reading Arendt that suddenly GIFs of her alongside jokes made with the phrase “the banality of evil” began to populate the Persian-language internet world. Another time, following a conversation between a regime ally living in London and a scholar of political science in Tehran being shared all over social media, these very Arendt readers flocked to books by economist Ludwig von Mises in order to understand the free-market economy, making books on political economy hit the top of the charts in Iranian online bookshops and populate the windows of bookstores downtown and in the Tehran University neighborhood.

“These very Arendt readers flock to books by economist Ludwig von Mises in order to understand the free-market economy, making books on political economy hit the top of the charts.”—Leili Entezari

In sum, the young whose lives are tightly entwined with accounts on X and Goodreads as well as online book clubs on Telegram continue to buy books that can cost them as much as one million, nine thousand tomans (around ten dollars), an amount that is hard for them to pull together in the current failing economy, in which their income has plummeted drastically to less than 250 dollars a month. These days, I am reminded of the phrase the “middle-class poor,” coined by scholar Asef Bayat in one of his last books, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (translated into Persian by Shirin Karimi); a middle class that has lost much of its resources but continues to do all it can to somehow keep connected to its class. In this context, what keeps college students and the older intellectuals, the so-called middle-class poor Iranians, tied to their class are books. They cannot travel as much, buy their Moleskin notebooks, or eat out at restaurants anymore, so they prefer to spend their evenings at bookstores. Many bookstores thus keep their doors open late and hold literary events in the evenings, while bloggers keep discussing books and sending the young generation out to buy books. Many bookstores in the downtown area are much busier these days compared to ten years ago. Books are the last bastions for this social class.

Independent nonchain bookstores also keep an eye on underground publishing since their young readers are once again into samizdat books. A two-volume samizdat novel by Mohammad Rezai-Rad, writer and playwright, has found many readers, and Rezai-Rad has promised three more books in the series. Meanwhile, samizdat copies of Tariki [Darkness], a novel by Hossein Abkenar, an exiled writer based in the US, continues to sell well. While there seem to be underground presses active in Iran, some Persian-language publishers based outside Iran, like Mehri in London, also arrange for their books to reach Iran. And bookstores where college kids and young readers hang out introduce these titles to their readers in hushed voices, never showcasing these books in their windows or on their tables.

The publishing world here in Iran, similar to its English-language counterpart, keeps itself afloat with popular books, manga, and best-selling thrillers which are adapted for the screen. The serious literary and theory portion of the market continues its life, too, though a smaller one, just like its audience size. This small group of readers seems all over the place with their interests these days. One day, they are thirsty for The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty, by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, suggested by an imprisoned political activist; the next, they rush to get a copy of Václav Havel’s The Power of the Powerless. Perhaps they are simply searching books to find a way out of their current complicated political and economic situation. In the face of price increases and sociopolitical issues, they are hesitant to respond with violence and rush into the streets to rally and bare their chests to bullets as readily as laborers and members of lower socioeconomic classes. Instead, they head into the world of theoretical disciplines and literature for ways to fight against this collapse.

Booksellers and Bibliophiles in Iran

by Rafa Rostami

translated by poupeh missaghi

In the second half of the month of Bahman 1403 (early February 2025), many cities around Iran finally saw some snow. We saw the downpour more so on our friends’ social media posts rather than on news outlets; the media headlines, however, as is customary these days, were filled with news of further drops in the value of our currency and the imbalance growing in the dollar/rial exchange rate. The snow was thus a welcome escape, allowing us to delay for yet another day our attempts to figure the whys and whats and hows of thehorrible conditions of the times. And the future, the future is never in our hands; it arrives of its own accord, just like that, and all we can do is simply sit around, idling and trembling in the dire winter cold, trying to keep a close eye on the exchange rate and the prices of this and that, beating ourselves up about why we ever thought becoming a bookseller was a good idea. Meanwhile, we feel obliged to tell our customers, as if narrating to them an adventure story, about the obstacles of our trade: explaining the fluctuating price of paper, the concept of copyright, the rent for storage, the risks of selling samizdat copies. We need to tell them all lest they think we are having things easy, forget that we are, like them, part of the same society.

So now, if amid all this, you ask us what Iranians are reading these days, we should say, cheap books! Cheap or free books. Iranians of course continue to read; no one would dare deny that. But today’s booksellers are not like those of the good old days who could sit on their wooden stools and read books, disregarding the hubbub outside their store, only looking up when the doorbell jingled and Mr. So-and-So came in for his weekly visits looking for copies of the hot-off-the-press books set aside for him. The old booksellers built up their careers by continuously reading and from time to time chatting with the writers of the very books they sold. But the independent booksellers we are today, we are out there training ourselves on every aspect of marketing: how to secure profit-making contracts, how to sell a variety of products, how to keep customers, etc. All this and in the end, we still feel guilty because we have to choose between our own good and the good of the young bibliophiles who hardly make a dime these days.

“In the end, we still feel guilty because we have to choose between our own good and the good of the young bibliophiles who hardly make a dime these days.”—Rafa Rostami

Those who have always read continue to read—that is true. But now they have to buy fewer books, secondhand books, smaller books with fewer page numbers, or preordered books paid well in advance, not yet affected by the most recent market turmoil. There are also those who sign up for memberships with audio or digital book services, which are relatively more affordable and give them access to an unlimited ocean of books on their phones, laptops, and e-readers. And then there are those who unethically download and offset-print PDFs of books and share them with others too.

Moving beyond book prices and affordability, if I want to answer the question of what titles are read more here in Iran these days, I should say the answer is perhaps not that different from the previous years or from those of other countries. Technological developments, on the one hand, make things hard for traditional trades like ours, but, on the other, we benefit from them immensely as well. Influencers, social media accounts, and websites advertising and reviewing books have been a big help introducing both booksellers and customers to the latest titles. As soon as a book or author shines on the other side of the world, they find fame in Iran as well. If a book becomes a trend in the US, it is soon published here, too, and does find its readers in no time (on the condition that it survives the censorship hurdles). Some publishers seem trained to grab such titles, titles we are sometimes clueless about, and publish some five thousand copies of them (a number not too small for the Iranian market); then, instead of selling them through us booksellers, they first sell them off online only. Sometimes, we are suddenly faced with an onslaught of teenagers who are looking for a title introduced by a young Korean singer. Grateful to the youth who are introducing us to a new literary star, we get to work, but before we even start to follow the Korean singer and his literary tastes, we find ourselves drowned in the news of a memoir by a famous actor who has just committed suicide, a book we realize many young readers have already read in English, before it’s even published in translation. The rest of our work is focused on titles that sell well and help ease our financial struggles—self-help titles that I’m not sure whom they benefit more, publishers or readers? Titles offering their readers atomic habits, inviting them to join the five a.m. club to become wealthy, and to parent kids who can then believe in giving thanks to the world and so on and so forth, while the poor parents continue beating themselves up to keep things and themselves together in the chaos of daily life.

Meanwhile, translations of works by big Russian, British, and French literary figures, as well as of Nobel Prize winners continue to be published. These works we wholeheartedly introduce to our customers, yet there are only a few hundred readers who come to us wholeheartedly to buy them, readers who are not struggling with the nightmares of hundreds of unread books in their libraries or don’t care about these nightmares. Alongside them, we also have our dozens of book-lover friends and regular customers who come and sit with us by the register. With them, we can complain all we want but also tell stories of the lovely people who honor us with their visit to ask for a rare book they haven’t found elsewhere, because they guessed we would keep a few old copies in the back for a day like this—we both know the value of an edition published long ago is in its containing sections that have been subsequently censored or rewritten in later print runs. So, there is no way we are going to thwart their hopes, turn them away emptyhanded to spend the money saved for a book on no matter what. As long as these good Iranians continue to come up the building stairs to open the doors to our first-floor bookstore, as long as they believe in us booksellers, we will be here.

Gatekeepers

by Moeen Farrokhi

Nearly ten years ago, when I was dreadfully and in small steps translating some essays and short stories by David Foster Wallace, I had an almost religious belief in what the man himself described as the “imaginative access to other selves” through literature, in a way that is “nourishing, redemptive.” Essentially, all I wanted to do was to share his pieces with Iranian readers, to give them access to the writing that, complicated as it was, might have made them feel less alone inside—just as it had for me.

Gleeful, oblivious, I handed some of the translations to a few literary gatekeepers—magazine editors and publishers. Their comments were polite variations of “Wow, this man is brilliant,” followed by “But he is too complicated. Those long sentences, couldn’t you break them down? You know, we live in a harsh economic situation, we are a suppressed society, we can’t afford that much concentration on a literary text. Americans can.”

Despite the prominence of translation in the Persian-language literary market, when it comes to challenging literary texts, publishers’ arguments are always the same: We need books that speak directly to our struggles. They, in the Western world, live in a different world, in their own kind of reality, one that allows them to do all the literary acrobatics they want. But we need to learn, through literature, from our history and those of the ones who have survived similar suffocating conditions of censorship, exile, and silence. A lobster festival? Irrelevant. Entertainment? Oh, we barely have time to entertain ourselves, let alone read and critique it. Wallace’s subject matter and aesthetics did not fit the demand, gatekeepers told me. The market wanted relevant literature, from the Eastern Block, Latin American. The ones that get us. I have never doubted that we need to learn from our past, to preserve our memory, to read how oppression affects people, yet was that all there was? Is relevancy all Wallace and the authors who try to push the literary boundaries could possibly offer?

“I have never doubted that we need to learn from our past, to preserve our memory, to read how oppression affects people, yet was that all there was?”—Moeen Farrokhi

Admittedly, Wallace, particularly in his Infinite Jest, which I ended up translating later on, was culturally too American and his text complicated, maybe too complicated. Unreadable, one might argue. َEven, untranslatable. Indeed, he is certainly not as relatable as Ariel Dorfman, nor is he as accessible and entertaining as Haruki Murakami, Paul Auster, and others who are favorites with Iranians. You can’t just open his book, relax, and read it in one sitting. Wallace unsettles, exposing one’s tolerance for a text that constantly folds on itself and shatters the image of what could be a great “readable” story. Also, perhaps like most English-language writers, he never imagined—needed to imagine—his craft being, or not being, translated. Yet, there I was, grappling with his text to bring it to my fellow Iranian readers. Great literature demands that we go beyond our presumptions and shed our habits of reading to hopefully land on a territory that is not exactly what the market can measure, predict, or shape ahead of time. Before the recent economic hardships, constant sociopolitical paradigm shifts, and the prevailing demands of the market, many ground-breaking authors—Faulkner, Proust, Woolf, to name a few—were translated into Persian, interweaving the fictional and the lexical in ways that required effort and patience from their readers, to then gift us access to the worlds that otherwise would be inaccessible, undiscovered.

Although nowadays the literary market and most of its gatekeepers seem less patient with texts and less willing to challenge themselves than the literary enthusiasts and actual readers, no one actually knows what the market truly demands. Wallace’s popularity with Iranian readers is solid evidence that literature can outdo the market. The market might have a tendency to see us readers as predictable and homogeneous, or make us as such, but readers—and translators as some of the closest readers out there—have unquantifiable desires. Many of us yearn to read works that truly rewire our minds, expanding our capacities to understand the world, to reach a moment when we feel the click—what Nabokov called “a tingle in the spine.” That moment isn’t about readability or relatability; it’s the moment when the boundaries of the market dissolve, creating a sanctuary where we and they nourishingly meet face to face, where readers feel less alone inside.

Sepideh Nazaralizadeh (b. 1993) is an Iranian interdisciplinary artist exploring storytelling through various media and art forms. With a BA in dramatic literature from Sooreh University, she has spent the past decade working as a playwright, director, performance artist, podcaster, and photographer, experimenting with theater and multimedia arts to shape new narratives.