Self-Translation

Veronica Esposito looks at the strangely fascinating imagery authors have used to describe self-translation and the battle between two languages, from Jhumpa Lahiri’s macabre metaphors to Ariel Dorfman’s self-described “bed where the two vocabularies coupled.”

Writing in her book Translating Myself and Others (2022), celebrated author Jhumpa Lahiri offers two curious images to describe the feeling of authoring a work in Italian, ever aware of the overwhelming likelihood that she will one day self-translate it into English (see WLT, Sept. 2022, 57). She first describes this awareness in the guise of a premature blossom growing on a plant, “like a bulb that sprouts too early in mid-winter.” Essentially, she is posing the English version of her work as some sort of beautiful but unwanted, almost deviant outgrowth of the creative act, one that prevents her from being completely at one with her Italian prose.

Lahiri then goes a step further with her second image. She claims that “everything I write in Italian is born with the simultaneous potential—or perhaps destiny is the better word here—of existing in English. Another image, perhaps jarring, comes to mind: that of the burial plot of a surviving spouse, demarcated and waiting.” Here, she goes far beyond the image of the deviant blossom, seeing the inevitability of self-translation as akin to that of growing old and dying.

Lahiri’s take on self-translation is fascinating for its morbidness, its tones of aberrancy, decay, and death.

Lahiri’s take on self-translation is fascinating for its morbidness, its tones of aberrancy, decay, and death, the way she poses it like some disease that inevitably contaminates the creative act she undertakes in Italian. It is important to note here that Italian is not Lahiri’s first creative language but rather one she adopted after becoming wildly successful as an English-language author. More on that later; for now, let us investigate further.

As with Lahiri, other authors have reached for strangely fascinating imagery to describe the act of self-translation. Indeed, there seems to be something about the practice that inspires authors to reach for such delicious ideas. For instance, Vladimir Nabokov once declared that self-translation was like “sorting through one’s own innards and then trying them on for size like a pair of gloves.” The Chilean author Ariel Dorfman, who used self-translation as a means of approaching the horrors that he lived through during Chile’s fascistic regime, called it “a sort of oblique mirror that allowed me to see the events in a different (or at least tolerable) light, work through this confession, show myself, perhaps reveal myself, use the distance, treat myself as an almost fictional object.”

If nothing else, self-translation clearly strikes a nerve in many authors, impelling them toward creative images and actions that they would not take otherwise. A good example of this is the self-translation collaboration that Borges made with his longtime English-language translator Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Di Giovanni was among Borges’s first translators, helping bring the Argentine master to global acclaim, and he was unique in working alongside Borges in Buenos Aires, holding in-depth conversations with him while bringing his works from Spanish to English. This is how scholar Dominique M. Louisor describes this remarkable collaboration:

[When translating with di Giovanni] Borges was the author of the source text as well as of the target one. According to di Giovanni, Borges welcomed and encouraged changes, and even insisted to altogether eliminate one particular passage, which to him had no reason to be in a version in English. Likewise, he agreed to add elements that were not in the original. . . . The translating of Borges by Borges is an ultimate form of re-creation and re-writing. One would expect an author to jealously protect his original creations. For Borges, translating his own works was the opportunity to create again and to take the inspiration further from the limit of the original Spanish text.

There is something pleasing about the way authors view self-translation for how it knocks the original text off the pedestal that we are so accustomed to placing it on. (Writing this, I now notice how less scandalous it feels to recall Gabriel García Márquez’s famous declaration that Gregory Rabassa’s translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude was better than the original.) Lahiri says as much when she writes that “the brutal act of self-translation frees oneself, once and for all, from the false myth of the definitive text. . . . The act of self-translation enables the author to restore a previously published work to its most vital and dynamic state—that of a work-in-progress—and to repair and recalibrate as needed.”

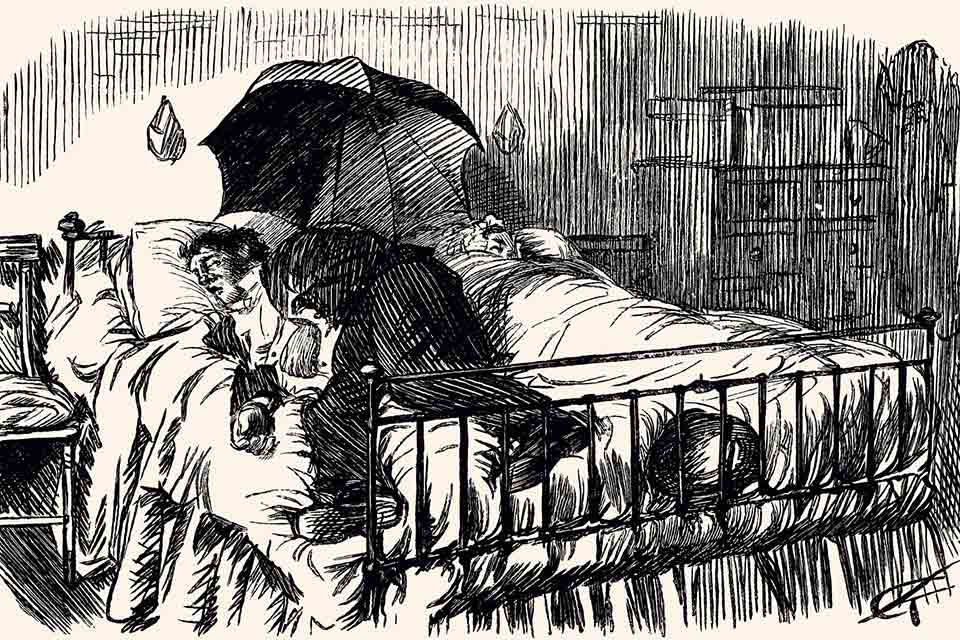

Dorfman poses his Spanish and English like an old married couple, arguing over which will get to author a book about his experience of the coup in his native Chile.

In a brilliant essay entitled “Footnotes to a Double Life,” Dorfman poses his Spanish and English like an old married couple, arguing over which will get to author a book about his experience of the coup in his native Chile. For months he watched them battle it out, himself “the bed where the two vocabularies coupled,” ultimately realizing that his truth could only come about through the act of translation, joining the two languages. “To unveil one’s origins, to journey to where it all started, we may need to use a different tongue, create an alter ego and trust him with the furtive truth we have told no one. You can’t journey to your origin without a translator of some sort by your side.”

Something implicit in these author statements is the idea that self-translation usefully disrupts the original, that this action of demoting the original text from its exalted status unlocks creative freedom for the writer. One fascinating instance of this comes from what is almost certainly Samuel Beckett’s best-known quotation, which reads “you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” These are the final lines of his masterwork The Unnamable, as translated by Beckett into English from his French original, but the French itself reveals an important difference: “il faut continuer, je vais continuer.” It omits the crucial phrase “I can’t go on,” which has become an integral part of this quotation that so many now use to sum up Beckett’s existentialist worldview.

As scholar Dirk Van Hulle notes, Beckett’s self-translation strangely made the original “incomplete,” an issue that Beckett ultimately addressed after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971:

As a result of the tension between the last two sentences, this line became one of the most famous Beckett quotes. But one tends to forget that it is a translation. Before Beckett translated it, the original was the only version and therefore “complete” by definition. Due to the addition in the translation, Beckett paradoxically made the original less complete. The translation retroactively created a sort of “gap” in the original. . . . After Beckett received the Nobel prize for literature in 1971, Les Éditions de Minuit decided to publish a new edition, which allowed Beckett to revise his text. On this occasion, he filled the gap created by the translation, completing the French text by means of the words “je ne peux pas continuer”: “il faut continuer, je ne peux pas continuer, je vais continuer.”

To return to Lahiri, I wonder if her macabre metaphors for self-translation have to do with the fact that Italian is an acquired language—if writing in Italian was an act of creative liberation, perhaps moving back into a native language would come with a certain heaviness. She suggests this possibility when she writes late in the essay, “something was driving me, in Italian, to speak for myself. I have now assumed the role I had set out to eliminate, only in the inverse. Becoming my own translator in English has only lodged me further inside the Italian language.” To write in two or more languages is to live inside of a complicated relationship, indeed.

Let me give the final word to Canadian author Nancy Huston, who writes primarily in French but also frequently composes in her native English. She sums up how agonizing it can be for an author to have more than one language to choose from and what a fraught, yet also potentially rich, subject self-translation can be:

Do I take the same liberties with the French language as I do in English? No idea. Don’t want to know. Want out of this dead end. . . . Yes, to tell the truth I’m going through a sort of crisis just now. The theme song is “I can’t go on like this.” Writing two versions of each book. Dying of boredom. Translating sentence after sentence after sentence, who else has endured this tedium? God, how I long to say, Okay, folks, enough of all this schtick. From now on, I’m gonna write all my books in . . . and choose one of the languages. But which one? Handicapped in both, not happy, not satisfied, because if you’ve got two languages, you haven’t really “got” any language at all.

Oakland, California

Editorial note: For more on translating Borges, see Norman Thomas di Giovanni, “At Work with Borges,” Books Abroad 45, no. 3 (1971): 434–44.