Tashkent, Uzbekistan

You see a lot from a train window, and after a few days of railing through Uzbekistan, I detected a nationwide fondness for ceramic storks. They were white and black with orange beaks, the sort that deliver babies and make nests on Spanish telephone poles. They were everywhere—in Khiva, Samarkand, Shahrisabz, and Bukhara; on the roadside, in gardens, atop fountains and monuments. Because I hadn’t seen any real birds of that kind, I thought they might be decoys, or a deterrent to some other creature, or omens of goodwill, like the storks in Hans Christian Andersen’s tales, who deliver siblings to well-behaved little children.

I turned to literature for answers. Alexander Burnes, nickname “Bukhara Burnes” for having established British contact with that city during the Great Game, wrote in his 1835 memoir Travels into Bokhara (sic) that “Most of the domes of the city are thus adorned, and their tops are covered by nests of the ‘luglug,’ a kind of crane, and a bird of passage that frequents this country, and is considered lucky by the people.” A generation later, Hungarian Turkologist Arminius Vámbéry visited the region and reported in his 1864 book Közép-ázsiai utazás (Travels in Central Asia) on “single-legged sentinels, upon the roofs” and “clumsy towers, crowned, almost without exception, by nests of storks.”

Yet today is a different world. “The birds are gone,” a man told me in Bukhara. “No water, no birds.” It was the Soviets, he said, who had closed the open reservoirs and drains that had been used as watering holes, and who had diverted the rivers that fed the towns to feed vast fields of cotton. One of many outcomes of this divestment was that the storks had departed. In Bukhara, only a reproduction of a nest, with two clay avian occupants, remains atop a blue-capped minaret of Chor Minor Madrasah.

In Tashkent, the crane figures took on an opulence of pearl and silver, their wings unfurled in a wreath of lustrous, feathered glory.

Then, in Tashkent, the crane figures took on an opulence of pearl and silver, their wings unfurled in a wreath of lustrous, feathered glory. It was something different: a Phoenician rebirth. And that it was: the stork sent packing by the Soviets in 1991 was reconfigured and reembraced by the newly independent Uzbekistan as the Huma bird. The Huma, mythic and strange, has international appeal. Borges called it “the bird that is somehow all birds,” while Ivan Bunin wrote that its “shadow brings to anyone on which it falls majesty and immortality.” Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. made it a parable in his essay “The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table,” saying, “I am like the Huma, the bird that never lights, being always in the cars, as he is always on the wing.”

Autocrat was apt in Uzbekistan. First the khans, then the tsars, then the Soviets, then the sham elections of today. Islam Karimov, who ruled from the moment of independence in 1991 until his death in 2016, was reputed to have boiled his political enemies alive. Incumbent president Shavkat Mirziyoyev, while no boiler, is still reticent to allow much dissent. Books by Uzbek writers Nurullo Otakhonov and Hamid Ismailov are on the forty-page blacklist, a compendium that at least seems designed more for iron-fisted stability than demagoguery. Also banned are Islamic screeds with titles such as “Democracy, an Infidel System” and “The World Is Being Filled with Corruption.”

In Tashkent, I was staying in what appeared to be the car-washing district; on every street there were at least two facilities, and soapy water was constantly seeping across the pavement. It was near the hospital where Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s seminoma was treated in 1954, the episode he later fictionalized in his book Cancer Ward (itself full of references to crooked, awkward birds with clipped wings). There is little of Tashkent in that book until the end, when Solzhenitsyn’s surrogate character Kostoglotov, on his single free day from the hospital, wanders the streets and finds himself looking at the monkeys at the zoo. That zoo is gone, replaced by Magic City, a kitsch monstrosity of both epic and miniature proportion, with London’s Tower Bridge and Big Ben, Dutch canal houses, Samarkand madrassas, and the Disney princess castle reproduced as schlocky reproductions.

Nearby is the Alley of Writers, a garden-hemmed arcade with statues of figures of Uzbek and Turkic literature, the mononymous poets Ogahi, Furqat, and Choʻlpon, among them. This was a peaceful, quiet place, but it didn’t say much about what Uzbeks were reading, so I walked across town to a bookstore, Kitob Olami (Book world). There was some confusion—it had recently been halved to make way for a co-working space; I was asked to leave the latter for not paying entry, something I was happy to do with all the neon tat about. Then Kitob Olami appeared not to exist, as Asaxiy, the name of a local electronics outlet, was splayed over the bookshop’s proper entrance. Despite the confusion, there were books and a solid flow of customers.

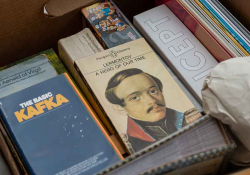

The shelves held a surprising number of used English books: dozens and dozens of worn-out romances but also some Henry James, Roald Dahl, and Elizabeth Gaskell. I asked the store minder, Sanjar Karimov (no relation to the ex-president), a nervous young man, about the used English books. They came from Dubai, he said. I was nonplussed: Dubai? Why? How? But he didn’t know the answer; the boxes arrived, and he duly unpacked them.

The most popular local books, he said, concerned business or were Russian and Uzbek translations of English-language titles: Jeyms Joys’s Uliss, Oskar Uayld’s Dorian Greyning Portreti. Sherlok Xolms and Agata Kristi were especially popular. On the store counter was a stack of a new English printing of Abdullah Qodiriy’s O’tkan Kunlov, translated by Mark Edward Reese in 2018 as Bygone Days. It was the first time, he said, the book had appeared in English. It was a classic Uzbek tome, a love story set in pre-Soviet times, posing questions of tradition, religion, and progress. (Qodiriy, too, was banned, then executed in 1938 during Stalin’s Great Purge.) Sanjar had read it in school as a ten-year-old and again last year, at the age of twenty-four. Did it land differently, I asked? He thought a moment. “It was newer,” he said. “Or maybe I am different. We have less censorship now. I read many more books.” And Hamid Ismailov, I said. You know him? Sanjar chewed his lip, shook his head, and asked, “Is he Russian?”

Gladstone, Manitoba

Editorial note: Hamid Ismailov served on the jury for the 2022 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.