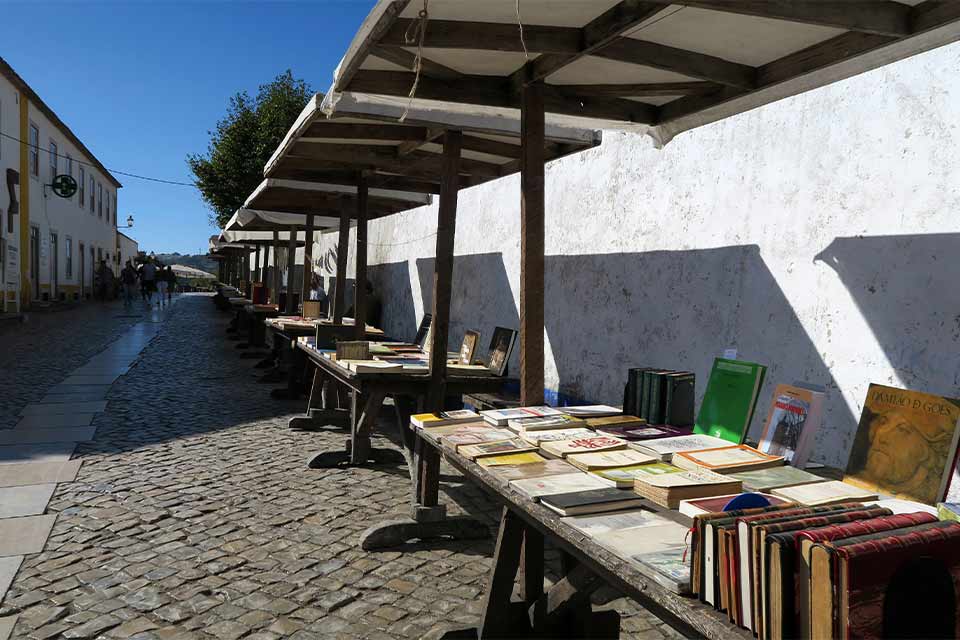

Óbidos, Portugal

Literature can change the way we celebrate. The bull-running and fighting of Spain’s San Fermin festival was just a local affair before Hemingway brought it worldwide fame in The Sun Also Rises. In the Shetland Islands, Haldane Burgess guided the Shetland Islands’ Yule celebration of Up Helly Aa from a disorganized pyromaniacal frenzy into something more Scandinavian (albeit still pyromaniacal) with his 1894 novel The Viking Path. And not a few have gone to Mexico for the country’s Día de los Muertos holiday to seek some of the alcohol-fueled oblivion found in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano.

The locations of these novels—Pamplona, Lerwick, Quauhnahuac—were all obscure places, not theretofore well known beyond their localities. They certainly were not literary hotbeds. Yet literature infused them with new, wider meaning; story brought them into focus for themselves and for the world.

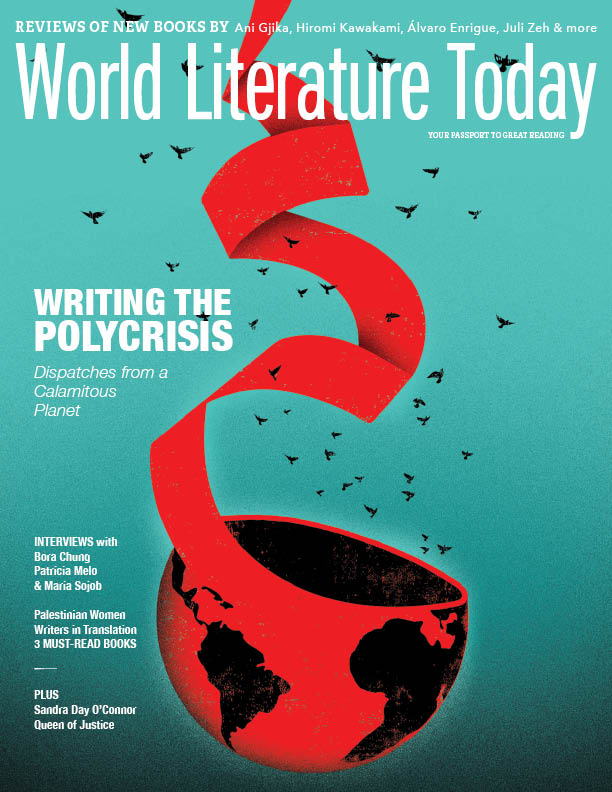

There have been no novels set in Óbidos, but literature has nonetheless been the catalyst of the Portuguese hill town’s rejuvenation. In 2015 the first annual Festival Literario Internacional de Óbidos, or FOLIO, instigated the town’s ascension to a world City of Literature. Since then, FOLIO, which takes place each October, has become one of the great literary festivals of the world, drawing international artists and Nobel winners into its circle. A second springtime festival, Latitudes, dedicated to the intersection of literature and travel, followed in 2017. The literariness of Óbidos is not confined to the festival: the town offers an international residency program for writers and confers annual literary prizes—the Prémio Armando da Silva Carvalho and the Prémio Discoveries da Via Verde.

In 2023 I accepted an invitation to attend that year’s FOLIO, where, among others, Geoff Dyer, Mariana Enriquez, and Brazilian singer Ney Matogrosso would be speaking. I wasn’t as important, just an observer with a notepad.

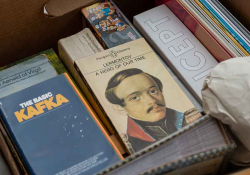

Books can be hard to find in some rural villages, but in Óbidos they have taken over, in much the way ivy creeps over a house. There are supposedly fourteen bookstores in the small town of three thousand, but they can be bought almost anywhere: cafés, wine cellars, trinket shops, and museums. They sit among the shelves of fresh vegetables and flowers in Mercado Biológico. They fill the Igreja de São Tiago, once the town’s largest church and now the Great Bookstore of Santiago. Secondhand donations find their way to the Book Exchange, run by the Silver Coast Volunteers, an expatriate collective in the area. And forty thousand titles fill the Literary Man Hotel—in bookcases that don’t cover the walls so much as they are the walls, going up two stories. But why, among all those sun-stained spines, was it so easy to spot doubles in those voluminous stacks? I saw copy after copy of James Herriot’s Dog Stories, William Trevor collections, Austen and Brontë, and a distressing amount of E. L. James. After I saw Dickens’s Hard Times no less than eight times, I felt obliged to get a copy.

Reading of the smoke and grime of Coketown (the setting of that novel) only brought out the beauty of Óbidos: the crenelated castle wall, the great column of the castle keep, the gleaming white walls trimmed with blue, with clumps of orange trees and purple bougainvillea.

Meals were taken collectively in the medieval basement of the Josefa d’Óbidos Hotel—writers, volunteers, and performers all dishing out plates of roasted pork and octopus together, all drinking from the same keg of tannic house wine. At the next table was the Spanish poet Elena Medel, who was there to promote her first novel, Las Maravillas (The Wonders), and getting another plate of batatas a murro was Colombian writer Héctor Abad Faciolince, who, only a few months before, had been in a missile attack in Ukraine. He had recounted that story to me, the strike occurring during a dinner with Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina. Faciolince was injured; Amelina later died of her injuries.

Daily writers’ talks were centered thematically, and war was one; Portuguese reporters Cândida Pinto and Ana França discussed their experiences. Elsewhere, Norwegian novelist Vigdis Hjorth and Italian writer Beatrice Salvioni discussed memory. Others spoke on desire, love, belonging. Each evening, there were music concerts and bars spilling light onto the narrow streets where readers (always readers, always with bags of books) drank and ate in the chill autumn night. Between the solitary acts of writing and reading, there was vibrancy, life, and discussion.

FOLIO had given a great gift to this small town, now an enclave of the collective nature of books, where ideas written and ideas read, ideas of peace and mercy, might find some purchase. Because reading is perpetual rejuvenation; always the opportunity to find ourselves in someone else’s words, always an opportunity to be reborn, remade, revealed.