Editor’s Note

The volcano is perhaps no longer just the symbol of social or warlike violence but the metaphor of a real

ecological time bomb to come. —Charif Majdalani, “Dancing at the Foot of a Volcano”

For more than a decade and a half, World Literature Today has been taking the pulse, so to speak, of writers’ responses to the planetary climate crisis. In special issues from 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2019, poets, essayists, and novelists, in dialogue with scientists, have been watching, with a mixture of incredulity and alarm, as the world seems to spin out of control around them. Watching, but also documenting the calamity and imagining futures both bleak and utopian.

For more than a decade and a half, World Literature Today has been taking the pulse, so to speak, of writers’ responses to the planetary climate crisis. In special issues from 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2019, poets, essayists, and novelists, in dialogue with scientists, have been watching, with a mixture of incredulity and alarm, as the world seems to spin out of control around them. Watching, but also documenting the calamity and imagining futures both bleak and utopian.

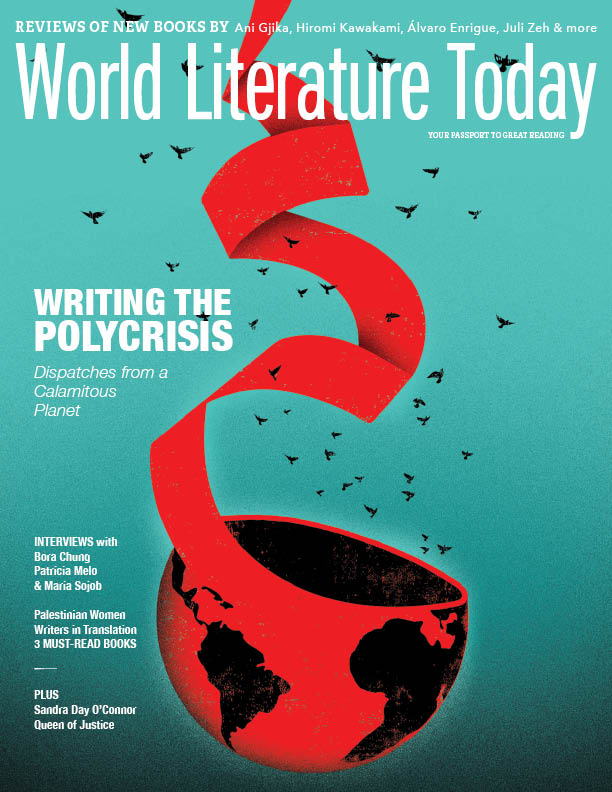

In WLT’s latest survey of international climate lit, “Writing the Polycrisis,” we lead with an essay by Richard Heinberg from the Post Carbon Institute. “So many new and serious threats are appearing, and so quickly,” Heinberg writes, “that a word has come into currency to describe this unprecedented convergence of risk—polycrisis.” And the stakes of polycrisis—what Heinberg calls the “scale of consequence”—have become increasingly incontestable. Heinberg clearly explains that the “risk/crisis generating machine” of fossil-fueled capitalism can’t just be unplugged, however. Ultimately, he concludes, we have “become our own worst enemy,” and “there may be no path forward that does not require a significant sacrifice of wealth, dominance, or comfort. . . . Collective survival will require setting aside our hubris and coming to terms with environmental and social limits.”

Heinberg sees some glimmer of hope in that humans are “smart, linguistic, ultrasocial, tool-making primates.” Writers, as linguistic tool-making primates par excellence, have long held up a mirror to the natural world. Poets, in particular, draw on the aboriginal connection between the self and a sense of sacred connectedness to the land in a primary way. Philippine Canadian poet Rina Garcia Chua, writing in the aftermath of the wildfires and heat dome that ravaged the Pacific Northwest in 2022–2023, offers a poem suffused with grief—grief that sits at the bottom of her speaker’s lungs, colors the dusk “spectral orange,” is swallowed in her dreams, that “skids and writhes” against everything she touches. “I inhale a breath,” she writes, “to resist the collapse of a chest. / Some air to run with; some lips to sing with.” In “Dead Horse Bay,” Venezuelan poet Santiago Acosta catalogs the detritus of our throwaway culture in the liminal space of an island atop an old landfill jutting out into Brooklyn’s Jamaica Bay. Three poems by Guaraní Argentine writers, translated by Whitney DeVos and Valeria Meiller, also take place in fragile ecotones; in Ana Gayoso’s “Archaic,” the “soul’s force burns” in a landscape by turns Edenic and decimated. And in speculative fictions by Ghanaian writer Cheryl S. Ntumy and South African writer Vuyokazi Ngemntu, the respective female narrators manifest struggles for political and bodily sovereignty via environmental allegories, one utopian, the other dystopian.

When WLT’s editorial team first began discussing the idea of this issue, we envisioned a focus on the Global South, since that region bears the brunt of some of the worst effects of climate catastrophe. Yet however the Global South is defined, the geography and economics of the polycrisis know no borders. At the recently concluded United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28), the Joint Statement on Climate, Nature, and People—one of ten pledges in the final agreement of December 15, 2023—emphasized that “addressing climate change, biodiversity loss, and land degradation together” must be done in “a coherent, synergetic, and holistic manner, in accordance with the best available science.” In the face of overwhelming scientific evidence about the planetary scale of the crisis, synergies of culture and science can offer opportunities for understanding, emotional engagement, and perhaps a vision that promises something other than unrelenting despair.

Daniel Simon