Deconstructing Celia

A writer recalls how David Hockney inspired her, first as an art student and later as a writer, helping her navigate toward a different way of telling stories.

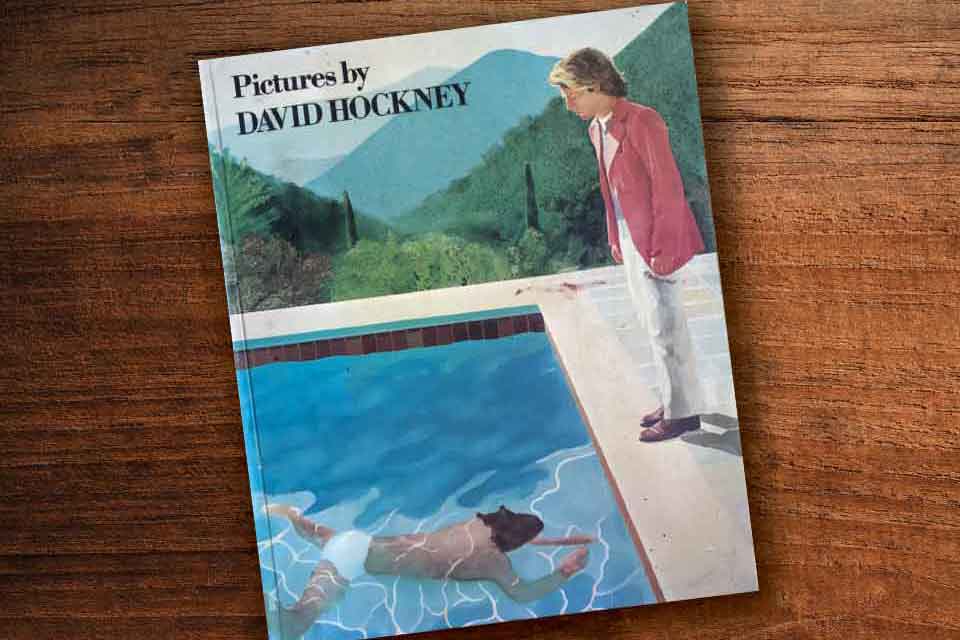

I was a young art student when I discovered Pictures by David Hockney. The book, published in 1979, was intended as a catalog of Hockney’s work to date, and the paintings, drawings, and prints, edited by Nikos Stangos, a guide to the artist’s development and working style. At the time, I was a first-year in painting at the San Francisco Art Institute, a school whose history was rooted in the gritty Bay Area Figurative Style, and where naturalism and domestic subjects like Hockney’s were far outside the norm. This was in the 1980s, when the influence of painters like Clifford Still and Richard Diebenkorn was still a force in the institute’s painting studios, and as we worked, often through the night, our pictures were not so much painted as unearthed through arduous trial and error. For a figurative painter like myself, who loved detail and surfaces, the modernist ideal of originality and authorship, what Umberto Eco called “the challenge of the past,” was weighty historical baggage. Modernism and formal exploration couldn’t hold my interest. I simply wanted to be a skilled practitioner of established forms, to paint the things I loved.

At the time, I knew something of David Hockney’s work. I’d seen his paper pools made of colored and pressed paper pulp, and his intricate photo collages, what he called “joiners,” neocubist constructions of portraits and landscapes. Pictures was my first experience of his paintings and drawings, and they were a revelation. The images of southern California, the split-level houses and swimming pools, the sprinklered lawns, the hard-edged light and towering Mexican palms, were familiar from a childhood spent in Los Angeles. Though I’d grown up on the east side, in a bicultural family of Jewish and Arab ancestry, and in the foothills of the San Gabriel Valley, in my grandparents’ community of Syrian, Lebanese, and Armenian immigrants, the beaches and affluence of the stylish west side seemed like another country.

And yet, the images in Pictures offered possibilities and reminded me of what I’d learned from a childhood spent drawing: that pictures could be personal, that they could tell stories. By the year of the book’s publication, Hockney had already painted some of his most recognizable works. He’d moved to Los Angeles in 1964 and soon after painted A Lawn Being Sprinkled and A Bigger Splash. In 1968 he returned to London and began a series of single and double portraits, many of which are included in Pictures and considered some of his finest works: art collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman in their LA sculpture garden; the artist’s parents seated on folding chairs, with fragments of paintings by Piero della Francesca reflected in the mirror between them; Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy in a symmetry of chairs and books. The double portraits are meticulous studies of character and connection, of time and place, and, as Kristen Knupp-Gehrke has observed, “reveal much about the relationship between the subjects and Hockney’s perception of them.”

The picture that made the greatest impression was Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy. Begun in London in 1969, the painting depicts the artist’s longtime friends, Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark, newly married in their Notting Hill Gate flat. It’s a portrait of a marriage and of the friendship between the three artists—Celia Birtwell is an acclaimed textile designer and Ossie Clark, who died in 1996, was a fashion designer who that year was at his professional zenith. The pair is posed in a classical arrangement, gazing at the viewer from either side of a louvered window, and their features are set against the room’s shadow and soft daylight. Celia stands in a long dress with a graceful bow, and Ossie is seated with the cat, Percy, on his lap. It’s a scene anchored by elegant geometry, in the planes of creamy walls, louvered shutters, the angles of a foreshortened table, and the print on the wall (one of Hockney’s from his set design for The Rake’s Progress), daylight grazing its thin gold frame.

The portrait suggested a way forward, in art and in life.

I recall learning the size of the picture, 84 by 120 inches, stunned the artist could sustain the rigors of hand and eye over so large a field. The picture was a feat of ambition, skill, and patience, and in the portrayal of the Clarks, I gleaned something of my own representational ambition. The figures backlit against the English light carried a story, the sort I imagined I wanted to tell. Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy portrays two characters in the visual language of body, mood, details of clothing—even the contre-jour light is part of their story. The picture spoke to something I sought for my own work but had yet to understand: that character resided in detail, and knowing which details to choose was a skill born of close observation. The portrait suggested a way forward, in art and in life. I’d grown up keenly aware of identity and difference, and the sense of an outsider looking in, I suspect, is part of what sparked my interest in narrative.

David Hockney was twenty when he was accepted to the Royal College of Art. This was in 1957, and right away he understood the school was divided into two theoretical camps. There were students who studied the traditional figure, still life, and landscape, and the more adventurous students who rejected the French model of formal study and gravitated to new forms, the Americans and abstract expressionism. In his introduction to Pictures, Hockney writes that on seeing the work of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, “young students had realized that American painting was more interesting than French painting.” Hockney, too, would give abstraction a try but soon abandoned it, finding the approach too barren for someone who loved drawing. And while his leanings placed him in the traditional camp, he still lacked a subject. Ron Kitaj, also an RCA student at the time, suggested he begin with images of things he was most interested in, at the time vegetarianism and politics. Gradually, Hockney arrived at the personal and domestic references that would define his work for decades, and form followed. “I was a traditional artist and painter,” he writes in Pictures, “in the sense that to me paintings should have content . . . my paintings always have content and a little bit of form.”

In Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, form is inseparable from content. There is pictorial emotion and restraint, a fidelity to the natural world, and careful rendering that tells a story. In his studies for the portrait, Hockey took preparatory photographs of the Clarks in their flat, and as Fayah Nayeri writes, upon concluding the bedroom offered the best light, proceeded to rearrange the room as though it were a set, moving furniture aside and selecting objects from other rooms—perhaps the intricate lamp that sits on the floor, the vase of lilies on the table, the lush deep-pile rug. Nayeri observes too that the Clarks’ portrait draws on Flemish painter Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and His Wife, painted in 1434. I’d grown up studying the picture in a childhood book, Famous Paintings, consumed by the narrative details that held stories of their own: the small dog in the foreground, the cast-off shoes, the domed mirror in the background that reproduced the scene from behind, in miniature.

As I studied the Clarks, my gaze always came back to Celia.

As I studied the Clarks, my gaze always came back to Celia. She was a stylish designer, the artist’s muse, nothing like the at-sea art student I was, but there was something in her portrayal I understood. Her self-effacing posture and open gaze served as an emotional and visual counterpoint to Ossie, who occupied the chair in an offhand manner, slouching with his head tilted away from the viewer. That incline gave his expression a wary look, while Celia projected an ease, a receptivity. At the time, these were only hunches, and yet, studying the picture, I kept returning to the hand on her waist, the red insets on her sleeve, the soft drape of the tie that falls from the neckline toward the floor, details that seemed a crucial part of her story.

Pictures also includes several drawings of Celia, from 1972 and 1973. Celia (red and white dress) was done after the marriage to Ossie ended. In the portrait, she’s seated in a Breuer-style chair, legs crossed, her profile in three-quarter view. Her dress has a daring bodice split at the décolleté, her hair is loosely pinned up, and her hands rest shadowed in her lap. Unlike her portrayal in the double portrait, Celia’s features here are precise; the lines of her nose and jaw are sharp and suggest a guardedness.

In Celia Wearing Checked Sleeves, she’s seen again in three-quarter view, half-reclining on an upholstered chair. Her arms are crossed, and she wears a pinafore-like dress over a voluminous blouse. The deep turquoise of the dress, the pale green of the blouse with its sumptuous bow at the collar, and the delineation of her eyes, which suggests careful makeup, might be the elements of a fashion illustration were it not for the choices Hockney makes. Her dress is defined by vigorous deep-green lines that move to purple in the shadows and pale gray in the light, and while the lines of her clothing are soft, against the white space of the paper they become austere.

Hockney took a similar approach in Celia in a Black Dress with Coloured Border. Seated on the same cushioned chair, Celia’s head rests on the cushion, legs crossed to one side. Her black dress forms a graphic diagonal on the page, and her legs beneath the dress pop with the surprise of red stockings.

In these portraits, Hockney shows us Celia, his longtime friend and muse, but he is also showing us the act of drawing and the pleasure he takes in stylistic choices. He shows us the process of selection, what about his subject will be told, his choice to linger on some details and merely hint at others. He shows us the energy a hand and eye bring to a passage of drapery, and the possibilities in subtraction over addition. Hockney means to show us Celia at a specific moment in time, but he also means to show us Celia as art. We know her through the marks of his crayon, and marks are the means by which the artist imprints himself on his subject.

Hockney means to show us Celia at a specific moment in time, but he also means to show us Celia as art.

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy and the Celia drawings guided me through my undergraduate, then graduate study of art. I continued to draw on the lessons I’d learned from studying her, even as the images I painted gradually became text painted directly on the canvas, an impulse driven by the stories I wanted to tell. “I’ve always been deeply interested in narrative,” Hockney said in a 1988 interview. “I didn’t go along with the modernist notion that narrative was gone.”

Two decades after I first discovered Pictures, I packed up the contents of my painting studio and sat down to write. The postcards pinned to the wall, of David Hockney’s paintings, were still there, a reminder that while the process had changed, my aim had not. I was still drawn to the ways detail revealed character, still drawn to surfaces and narratives that intersected with place. Only the medium had changed. Form and color remained; so did figure and ground, along with details that might reveal both character and story. David Hockney’s portraits of Celia didn’t lead me to a new medium, but they pointed to the possibilities and helped me navigate toward a different way of telling stories.

San Leandro, California