Exchanging Different Versions of Jokes with Ariel Magnus

I first came across Ariel Magnus’s work back in 2012 when I was working on an anthology of Argentine writers for the city government. The texts tended to be sent to me already excerpted with little context or explanation, and generally that wasn’t a problem: I can usually get the gist of a voice and plot pretty quickly, or at least well enough to produce a decent version in English. With Magnus’s texts, though, taken from the novel El hombre sentado (The sitting man), I was all at sea. El hombre sentado, I learned, is a kind of po-mo novelization of a film-poem by the Swedish director Roy Andersson, inspired by the poetry of César Vallejo. Or, in other words, pure existentialist angst filtered and condensed through various different mediums right onto my computer where it was about to undergo a transformation into yet another language. Having kind of gotten my bearings, I think I was able to produce a good rendering, but more importantly, Magnus was now very much on my radar.

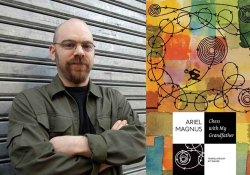

Looking through his bibliography, it was obvious that he’s a writer who likes to play with literary concepts and genres; heck, you can see it just from his author photo: the pate and facial hair seem specially designed to accentuate the sparks flying off of that mad-scientist brain of his. No doubt about it, I wanted to work with him. I got my first chance when the Short Story Project asked me to translate one of his stories, “Doing Your Duty,” for their extraordinarily ambitious program (check it out if you haven’t come across it before). This was a very different text from El hombre sentado, far more organic, gritty, and (oh, bane of translators) full of sparkling wordplay. This time I got to send my queries to Ariel, and we soon hit it off; essentially working on a translation with him boils down to exchanging different versions of jokes. It’s fun. Subsequently, Seagull Books asked me to translate his novel Chess with My Grandfather (originally scheduled for this year but now Covided into 2021), an extraordinary novel based around the diaries of a grandfather he never met and the World Chess Championship played in Buenos Aires in 1939; a blend of real life, madcap schemes, acute political, philosophical, and literary reflection, and, of course, lots of jokes. I hope I’ve done it justice.

But really all you need to know about Ariel is that he’s the kind of writer who thinks it’s a good idea to produce a book consisting of a hundred one-hundred-word stories and another hundred one- hundred-character aphorisms. And that he’s able to pull it off: some of these ministories boast more depth and brilliance than several rather well-regarded novels I don’t care to name. And all you need to know about me as a translator is that I think it’s a good idea to try and translate them. The challenge, obviously, was to match the word count, and I find that Spanish tends to shrink by about 10 percent when transferred into English, but that actually gave me (or rather us: I naïvely thought that the restrictions would reduce the scope for author comments; I was wrong) a little more leeway when trying to find the right combination of words and phrases to reflect what in the original is a glorious exercise in playful brevity. It’s for the reader to determine whether we’ve been successful.

Read Maude’s translations of Magnus’s flash fiction plus their conversation in our web-exclusive interview.