Aravind Adiga’s Last Man in Tower: Survival Strategies in a Morally Ambivalent India

Iconoclast Indian novelist Aravind Adiga’s Last Man in Tower, set in the maximum city of Mumbai, is not only the fight of one man against his times but also the collective agony of an ancient civilization fragmented by a post-truth era of indiscriminate urbanization. A close reading of the novel raises disturbing questions about contemporary ideas of national development and identifies survival strategies adopted by citizens in a morally ambivalent India.

The most patriotic thing a creative artist can do is challenge people to see their country as it is.—Aravind Adiga[1]

In an era of indiscriminate capitalist globalization and uncontrolled urbanization, when India strives to join the league of the global superpowers, a generation of Indian English novelists is engaged in exploring the bitter truths underlying India’s journey to success. Amid the glitter of smart cities, ultramodern corporate hubs, and vast industrial zones, some stories remain to be told—those of the native colonizers who appropriate common national resources, of farmers and tribals mercilessly plucked out of their lands, of the injustices heaped upon the middle classes, of the destruction of vital ecosystems to satiate capitalist greed.

In this context, this essay analyzes Aravind Adiga’s novel Last Man in Tower (Fourth Estate, 2011), focusing on the survival strategies adopted by ordinary men and women amid the ambivalence and emptiness in modern India that are the mainstay of the text.

The Novelist

Born in 1974 in Chennai, Aravind Adiga worked as journalist with the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, and Time magazine. His debut novel, The White Tiger (2008), won the Man Booker Prize. His novels Last Man in Tower (2011) and Selection Day (2016) have been widely acclaimed. Adiga’s work seems to be haunted by a Dickensian ghost. The million-dollar question that he grapples with is whether India’s progress is all-inclusive, whether her development has brought happiness to all, and whether her smart cities are also socially and morally sound cities. Adiga seems to conclude that Indians today live in a scary spiritual void wherein painful absurdity has become the price of progress.

Adiga seems to conclude that Indians today live in a scary spiritual void wherein painful absurdity has become the price of progress.

Last Man in Tower

Last Man in Tower (2011) can be summed up as the stubborn fight of one man against his times. It is set in the maximum city of Mumbai, where the future is defined by big businessmen and progress is measured in terms of skyscrapers. The protagonist, Yogesh A. Murthy, alias “Masterji” (a reverential term for a teacher in Hindi), a retired schoolteacher with more than the prescribed levels of idealism, finds himself out of touch with the increasingly practical and materialistic society around him. Even as all his neighbors gladly embrace the incredible offer of the ruthless builder Dharmen Shah to transform their ancient housing society into a glitzy township of skyscrapers, Masterji finds himself in the unenviable role of the sole rebel who refuses to sell his flat, the only obstruction to the demolition of the old Vishram society and the ushering in of a new era of prosperity and luxury for so many.

Villain and Victims: The Beginnings of Ambivalence

At the beginning of the novel, Adiga establishes the historical significance of Vishram Society, located in Vakola. Vakola is itself a paradox of development—it is adjacent to the Santa Cruz airport and also houses one-fourth of Mumbai’s slums. Vishramites symbolize the golden mean of Indian society—neither filthy rich nor abjectly poor, a hard-working people who have preserved their identity and dignity amid the buffeting winds of change. But this is an era and a species becoming fast extinct. With the end of these small certainties of life begins an era of confusion.

The first two books of the novel indicate the gradual takeover of Indian society by spiritual emptiness. Though he begins by pitting the villainous builder Dharmen Shah against the innocent lower middle class of Vishram Society, Adiga springs a surprise as the novel progresses. As he unravels life after life, the ambivalence deepens, for Shah is not as bad as he seems and the Vishramites are not as pure as they appear to be!

Dharmen Shah’s persona is clearly the product of the massive, silent class war that is fought in India every single moment. The yawning class divide is clearly illustrated in the description of Versova Beach: “Here, in this beach in this posh northern suburb of Mumbai, half of the sand was reserved for the rich, who defecated in their towers, the other half for slum dwellers, who did so near the waves” (83). This is again reiterated by builder Shah’s rags-to-riches tale: “In a socialist economy, the small businessman has to be a thief to prosper. Before he was twenty he was smuggling goods from Dubai and Pakistan. Yes, what compunction did he have about dealing with the enemy, when he was treated as a bastard in his own country” (88).

With all his immorality, Shah loves getting into the heat and dust and working alongside manual laborers on the construction sites and offering them tips. If this is the spiritual ambivalence of Shah’s generation, which is already middle-aged, the next generation, symbolized by Shah’s son, “Soda-pop” Satish, epitomizes spiritual emptiness. Satish, vexed with his father’s hypocrisy, has no faith, no emotions, and no feelings, except for the rage against his father and the sadistic pleasure of inflicting pain upon others.

On the other hand, when Shah extends his splendid offer to the people of Vishram, the characters of the Vishramites start to unravel. One by one, everyone, including the fiery Communists and the staunchest conservatives, falls prey to Shah’s sweet opulence, which stokes the embers of their undying desires.

Two Indias: A Crisis of Ambivalence

Books 3, 4, and 5 of Adiga’s novel delve into the causes underlying the moral ambivalence in Indian society while foregrounding the enormous pressure on an ordinary Indian to become rich. Further, Adiga tries to interconnect and investigate the class, value, gender, and environmental conflicts. Mary, the cleaning lady at Vishram, concludes that estate broker Ajwani’s evil looks “put a price on women.” In a similar fashion, builder Shah’s eyes always put a price on land. Shah’s plan of demolishing Vishram Society poses a threat to the livelihoods of Mary and other servants. When Dharmen Shah enthralls people with his plush constructions, Masterji visualizes the brewing ecological catastrophe. What makes contemporary Indians go against the well-being of their neighbors and turn a blind eye to the decimation of the very nature that sustains them? Who is going too far—the Vishramites ready for any battle to build a better home for their kids or Masterji willing to block the progress of all for the comfort offered by old memories? Who is right, the champions of idealism or the practical developers of glittering cities that promise to take India out of centuries of backwardness? There are no easy answers to these questions. As The National puts it,

Who is right, the champions of idealism or the practical developers of glittering cities that promise to take India out of centuries of backwardness?

Masterji’s moral grandstanding has removed any trace of empathy for the people around him. . . . Is he any less selfish than Shah? . . . And what of those suddenly persecuting him? Greedy hypocrites willing to betray long-standing companionship for money or vulnerable human beings simply trying to do the best for their families? This is where the distinction between Adiga and a Victorian novelist is laid bare. The latter’s public would have expected answers to questions like this. . . . Dickens, in spite of his genius and undoubtedly with half an eye on his popularity, would often submit to this whim. Adiga’s readership is less inclined to believe we live in morally straightforward times. It’s the ambiguity with which he draws the story—even as it becomes by turns tenser and more brutal—that makes it so powerful.[2]

In book 6, entitled “Fear,” Adiga presents a multidimensional view of the crisis at the heart of India. In the first face-off between Masterji and Shah, Adiga proves that amid all the ambiguity, India still has people who would not compromise their values for all the riches or terrors of this world. On the other hand stands Shah, the ambassador of a new India that moves on unbridled ambition and is fueled by limitless human greed:

What do you want? In the continuous market that runs right through southern Mumbai . . . one question is repeated, to tourists and locals, in Hindi or in English: What do you want? . . . Only a man must want something; for everyone who lives here knows that islands will shake, and the mortar of the city will dissolve, and Bombay will turn again into seven small stones glistening in the Arabian Sea, if it ever forgets to ask the question: What do you want? (230, 231)

The real test of idealists like Masterji lies in how effectively they combat the fear unleashed by real estate kings and a state apparatus subservient to the wealthy. Such is the level of distortion with regard to the definitions of nationalism and morality, that whoever opposes the self-seeking designs of the majority is branded as a “traitor,” an “antinational” element. As Gopalkrishna Gandhi, Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson puts it, “The troubled intellectual in India today is being asked to choose between free speech that can lead to intellectual murder or a silence that can end in intellectual suicide.”[3]

The Climax: Clarity amid Ambiguity

Book 7, entitled “Last Man in Tower,” the climax, ironically stands out for its markers of clarity. First, the old India of Masterji has a spiritual freedom that new India, irredeemably tied to materialism, can never have. Whenever Masterji remembers his wife, love and great strength fill him. On the contrary, Shah’s memories of his wife fill him with weakness, guilt, and shame. Shah’s only son abhors him. He is chronically sick from lung damage, thanks to the pollution in the construction industry, and his illness is as much moral as physical.

Second, the great survivor myth is busted and faith in humanity is sorely shaken. Masterji tells his lawyer, “Men of our generation, we have seen much trouble. Wars, emergencies, elections. We can survive” (282). But three pages later the same man prays to his dead wife Purnima, “. . . swoop down and lift me from the land of the living” (285).

Third, there is this vast communication gap between Old India and New India. Shah can never understand Masterji’s idealism: “A man who does not want: who has no secret spaces in his heart into which a little more cash can be stuffed, what kind of man is that? . . . I have seen every kind of negotiation tactic . . . But I have never seen the tactic of simply saying ‘No’ permanently” (287, 288).

Nevertheless, the clarity of Masterji’s vision pierces the darkness. Masterji’s idealistic fight is unsuccessful, as expected, but it is meaningful.

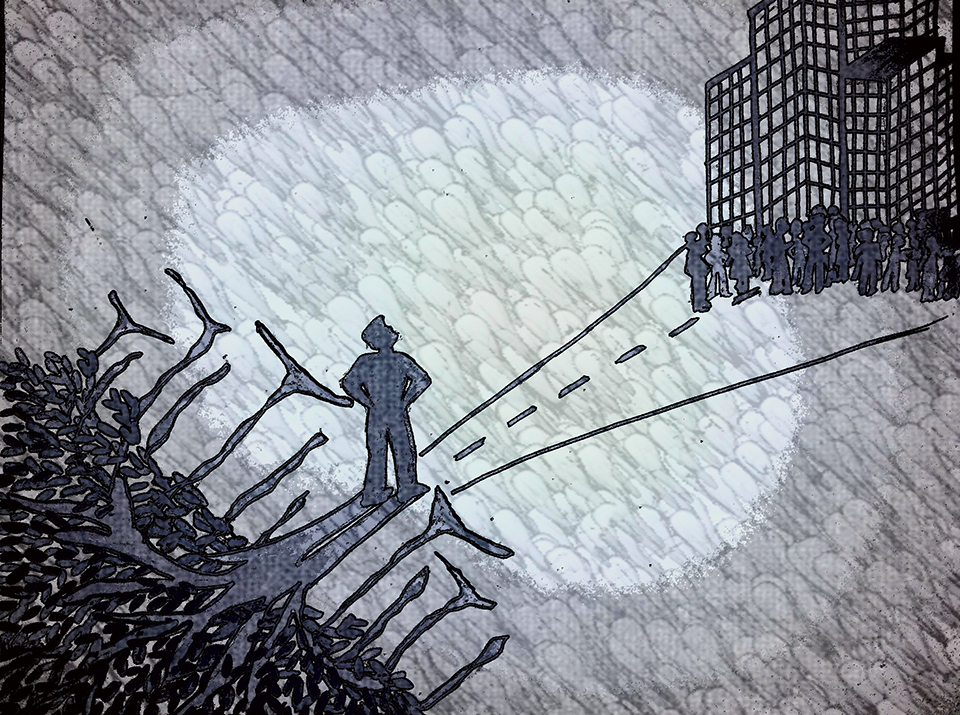

Until now he had only been conscious of fighting against someone: that builder. Now he sensed he was fighting for someone. In the dark dirty valley under the concrete overpass half-naked labourers pushed and slogged, with such little hope that things might improve for them. Yet they pushed: they fought . . . the straining coolies looked like symbols: hieroglyphs of a future, a future that was colossal. Masterji gazed at the light behind the dirty buildings. It looked like another Bombay waiting to be born. . . . Each one of the solitary, lost, broken men around him had a place in it. But for now their common duty was to fight. . . . Masterji . . . felt for the first time since his wife had died—that he was not alone in the world. (301, 302)

Masterji’s crusade has long ceased to be a personal one. Forcible usurpation of and forcible eviction from land and property is a burning issue in India. To quote from the Handbook on Forced Evictions in India,

. . . . urban renewal projects, sporting events, infrastructure expansion, environmental projects and more recently, the designation of large areas as tax-free Special Economic Zones, have resulted in the displacement of millions of families, most of whom have not received adequate compensation and rehabilitation.[4]

Grand Finale: Poetic Justice

Book 8, “Deadline,” is especially remarkable for the two-pronged attack mounted on Masterji—horrifying social isolation and brute force unleashed by the very neighbors whom he had selflessly educated for half a century, and Masterji’s Gandhian response to it. Masterji’s neighbors become the agents of the real estate mafia. By the time they execute his murder and project it as a suicide, Shah’s deadline for the demolition of Vishram has already expired and Masterji has overcome his fear of death. In his last moments, he is filled not with fear or sorrow but a sense of liberation that numbs all the pain. After Masterji’s death, the moral ambiguity continues. Ironically, his enemies now appreciate his courage. Even the heartless Shah is shocked. Vishram is torn down to make way for Shah’s skyscrapers, but the Vishramites fail to achieve the happiness or the compensation they had dreamt of. Most of them are preoccupied with assuaging their guilt. Some of them refuse the builder’s money and engage in educating street kids in memory of Masterji.

Conclusion: Novel of Conscience from the City of the Living Dead

Adiga’s novel thus offers a three-dimensional view of contemporary urban India. The reader’s eyes are permanently opened to some unpleasant truths that must not be glossed over while building the grand narrative of developed India. The novel has universal implications. It was published soon after the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, which resulted in the displacement of nearly 1.8 million people, according to Reuters. Similar incidents of displacement of the less privileged were reported from London and other cities that had hosted such major events. By the time Last Man in Tower was published, work was almost completed on Antilia, the world’s first billion-dollar skyscraper home belonging to Mukesh Ambani of Reliance group. Set amid the massive slums of Mumbai filled with abject poverty and squalor and built on land allegedly acquired forcibly from weak players and orphanage trusts at much less than the market price, it invited a lot criticism.

Nevertheless, the answers to a morally ambivalent age lie forgotten in India’s ancient wisdom. The closing lines of the novel offer an image of constancy—the old banyan tree of Vishram Society that, like Masterji’s spirit, survives the demolition, concrete rubble, barbed wire, and broken glass, to send out new roots and offer shelter to homeless families. In Indian culture, the banyan tree is a symbol of resilience, liberation, growth, compassion, and the wisdom of selfless giving. And looking at the tree, Adiga concludes: “Nothing can stop a living thing that wants to be free.”

Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh

Footnotes

[1] Susan H. Greenberg, “Tiger by the Tales,” Newsweek, June 6, 2009.

[2] Alan White, “Last Man in Tower: A Parable Built on Ambiguity,” The National, July 29, 2011.

[3] Gopalkrishna Gandhi, “The General Drift of Society,” The Hindu, June 16, 2016, 10.

[4] Shivani Chaudhry et al., How to Respond to Forced Evictions: A Handbook for India (New Delhi: Housing and Land Rights Network Habitat International Coalition—South Asia, 2014), 15.