Who Can Identify Byomkesh? The Mystery of the Missing Indian Mysteries

The impact of British literature on India was profound, altering the poetry, fiction, and drama of the many cultures and languages unified by the empire, and it has lingered. Victorian attitudes in public entertainment remained powerful enough to embarrass many Indians with the sexuality decorating their own ancient temples. Kissing was illegal in Indian cinema until the 1990s, though that has hardly slowed “Bollywood,” which annually produces twice as many films as Hollywood and was estimated by Forbes to be a $2.28 billion industry in 2014. Book publishing is a similarly gigantic industry. Nielsen reports that literacy is predicted to reach 90 percent by 2020, and one-quarter of the youth population (83 million) identifies as book readers. Although most books published are textbooks, as might be expected from a dynamically developing country, pleasure reading is a significant part of the market and promises huge growth as well.

Strangely, however, what is written in India tends to stay in India. The sixth largest book market in the world, India is second only to the United States as the largest English book market in the world. Indians have scattered around the world, providing Trinidad with barristers, the US and Canada with physicians, and the United Kingdom with skilled and unskilled labor. London has hundreds of curry shops, and George Harrison incorporated the unique attributes of classical Indian music into Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. But where are the Indian novels? Not the sacred texts like the Vedas or the Kama Sutra, which opened so many Western eyes—where are the Who-Shot-Johns?

India provides incredible backdrops, from the snows of the Himalayas to the plains of Kashmir to the crowded streets of Mumbai to the fishing villages of Andhra Pradesh. Christians, Muslims, Jains, Sikhs, and Hindus live together in harmony and often violent conflict. Add to this the tensions remaining from the traditions of the caste system and colonialism, as well as the unique and rich cultural history, and it is easy to see why such novels as A Passage to India, The Jewel in the Crown, Kim, Siddhartha, and Life of Pi were highly popular. The most familiar Indian detective, Inspector Ghote, was created by H. R. F. Keating, an Englishman who had never visited India when he wrote the first of the series. It is unusual for any Indian author to break through to success in the West. Even though they may write in Hindi or Urdu, many write in English, and the history between Britain and India should lead to more publication in English-language markets. Most of the Indian authors readers may recognize lived mainly in other countries, like Rohinton Mistry (Canada) and Salman Rushdie (Britain). Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things (1997) is singled out by Wikipedia as the best-selling novel in the world by a nonexpatriate Indian author.

One of the main problems in importing Indian crime novels is not just the traditional American antipathy toward translated books and “odd” foreign names but also the often-unusual phrasings in the Indians’ version of written English. A casual attitude toward the protection of intellectual property has also been blamed. Book piracy, especially of e-books, is said to be common in India, and there are thousands of publishers, big and small. When schlockmeister Harold Robbins was selling millions of potboilers like The Carpetbaggers, novels “by Harold Robbins” that weren’t written by Robbins crowded tables in India. This may have been the sincerest form of flattery, but flattery didn’t pay the bar bill for Robbins’s hedonistic lifestyle.

Another reason commonly, but furtively, voiced concerning Indian crime fiction is that it isn’t of high enough quality. This is something I have heard about a dozen nations’ crime writing and find impossible to accept, especially given the volume and increasing popularity of crime fiction in India. Ninety percent of everything is crud, according to Sturgeon’s law, but that includes the tsunami of Scandinavian translations and, to be blunt, 90 percent of our homegrown whodunits. That still leaves 10 percent of a very large number of books we could be enjoying. A disparity of taste might be a more credible explanation. Most Indian mystery writers have looked to the Golden Age as their model, a result of the usual fascination of colonial peoples with the secret powers of the strangers who have seized their land. P. G. Wodehouse was long one of the most popular authors in India—more so than Harold Robbins—and the English country manor, oh so civilized behavior, and the dynamic of upstairs/downstairs made it almost inevitable that Indians interested in the genre would seek inspiration from Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Edgar Wallace.

The Sherlock Holmes / James Bond of India is a gentleman master sleuth named Byomkesh Bakshi, for instance. Bengali-language author Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay was very prolific in many forms of writing and created Byomkesh in a 1932 novella. The subsequent books, movies, and television series have made the character familiar across the subcontinent. The stories of Satyajit Ray’s detective Feluda are at least translated for us, but that is likely because Ray is considered one of the greatest of film directors, a neorealist influenced by The Bicycle Thieves in the midst of a forest of Bollywood lushness. A Bengali, like Bandyopadhyay, Ray created Feluda first for a children’s magazine in 1965, but stories and novels continued to be published until 1995. Feluda was also popular in film and television. The stories are narrated by Feluda’s nephew, Topshe, with an obvious reference to the template of Watson and Holmes.

The Sherlock Holmes / James Bond of India is a gentleman master sleuth named Byomkesh Bakshi, for instance. Bengali-language author Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay was very prolific in many forms of writing and created Byomkesh in a 1932 novella. The subsequent books, movies, and television series have made the character familiar across the subcontinent. The stories of Satyajit Ray’s detective Feluda are at least translated for us, but that is likely because Ray is considered one of the greatest of film directors, a neorealist influenced by The Bicycle Thieves in the midst of a forest of Bollywood lushness. A Bengali, like Bandyopadhyay, Ray created Feluda first for a children’s magazine in 1965, but stories and novels continued to be published until 1995. Feluda was also popular in film and television. The stories are narrated by Feluda’s nephew, Topshe, with an obvious reference to the template of Watson and Holmes.

At present, though the Golden Age style still sells well to devoted fans, it seems a throwback, a particular taste for a limited audience. In the twenty-first century, Indian writers have made a concerted effort to branch out. Last January, the Crime Writers Forum of South Asia (founded only in 2014 by Namita Gokhale and Lady Kishwar Desai) held its third annual Noir Literature Festival in Delhi, featuring author panels such as “Modus Operandi,” “Judgment Day,” and “She’s Sexy When She’s Dead,” a title that just might be the ultimate noir title. To encourage the development of crime writing, the festival also offered workshops and inaugurated a prize for best short story. In this and the preceding two festivals, most of the speakers were not purely crime writers. Many were journalists, screenwriters, or literary writers, but writing is a tough way to make a living anywhere. In developing markets being versatile is often the only way. A half-dozen foreign writers of various stamps were also featured speakers in the conferences, with the Norwegian global best-seller Håkan Nesser and other writers from Norway, Italy, New Zealand, and Australia.

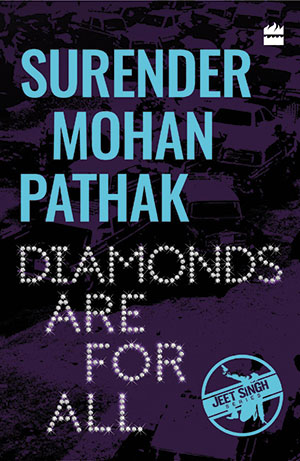

An honored participant all three years was Hindi-language author Surender Mohan Pathak. Even though other Indian writers preceded him in the genre, Pathak is the king of the Indian mystery. He might also be called the Simenon of India, having published 275 novels by 2017. Born along what became the partition line with Pakistan, he published his first mystery story in 1959 at age nineteen and his first novel in 1963. He has created several series detectives and a long list of “one-off” thrillers. Generally, his books are influenced by the Golden Age style and only a few have been translated. This is a misfortune for readers, perhaps, but it is definitely a tragedy for criminals. Several genuine crimes in India were inspired by ideas cadged from Pathak’s novels.

A large variety of ingénues might convince global readers to shift their focus from the bleak rains in the Scandinavian detective’s soul to the sunny subcontinent—if they can become available.

A large variety of ingénues might convince global readers to shift their focus from the bleak rains in the Scandinavian detective’s soul to the sunny subcontinent—if they can become available. Abheek Barua, whose day job is as chief economist for HDFC Bank, recently published City of Death. This is exactly the kind of thriller (think Jefferey Deaver) that has global potential. It jumps with enthusiasm on the serial-killer bandwagon and ferociously imports urban noir to Kolkata. Madhumita Bhattacharya has made her mark with three (so far) Reema Ray mysteries, The Masala Murder, Dead in a Mumbai Minute, and Goa Undercover. Ray is a private detective reminiscent of Kinsey Milhone and V. I. Warshawski, whose agency specializes in cases involving adultery among the wealthy. The debut novel of Reeti Gadekar, Families at Home, also drew much attention, leading to a sequel. In a classic mystery device, an apparent suicide is revealed as a murder, and her police detective finds himself up against political influence and moneyed obstruction, frequent tropes in Indian crime fiction.

Authors with a darker tone have also recently scored important successes, moving Indian crime fiction more toward what we would call “hardboiled.” Among the most hardboiled is Nikesh Murali, an expatriate poet turned novelist whose “literary god,” he says, is Cormac McCarthy. Murali offers a brutal counterpoint to the Western romanticism of Asian poverty and spirituality. As one reviewer wrote, “His Night Begins barely touches on the spiritual, but has a lot to say about the dirty side of India.” In it, a contract killer embarks on a brutal course of revenge against child traffickers. Dark military thrillers have also become popular in India. Author Shashi Warrier gave up a corporate job, moved to a village to write, and now has four thrillers to his credit. Sniper tells of a lieutenant colonel who hunts another sniper in the jungles bordering Myanmar while trying to deal with the rape and murder of his own daughter. The “Lashkar” series by Mukul Deva is set against the backdrop of the India and Pakistan hostilities, exploring terrorism and subjects like the training of children to be jihadis.

Dozens of other authors could be listed, most of whom are unknown here in the United States. Yet the talent and the will is certainly there. It will only take a few books to break through the cultural conventions, and the mean streets of Kolkata, Delhi, and Goa will intrigue us as much as London, Stockholm, and Paris.

Palmyra, Virginia