Editor’s Note

Every story had a face, a first and last name, a mother

or son, brother or sister, losses and days of triumph.

– Leonora Flis, “Zeroes”

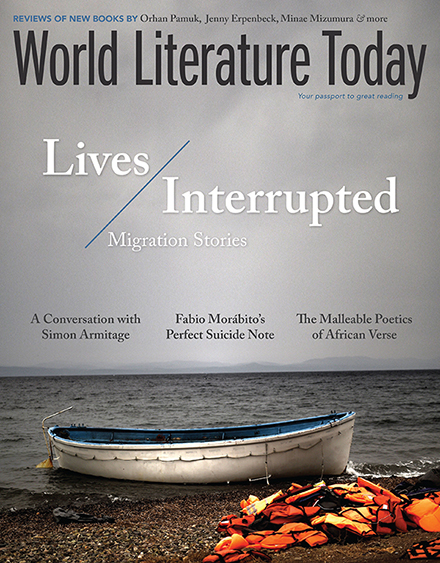

The haunting photograph on the cover of this issue, by award-winning Greek photographer Aris Messinis, poignantly evokes the “Lives Interrupted” theme that begins on page 47. Messinis captured this moment on the Greek island of Lesbos on October 8, 2015. An estimated one million migrants and refugees entered the EU that year, fleeing the devastation of war zones, political unrest, and economic misery. The empty boat and abandoned life jackets provide a visual backdrop to the short story “The History of Grains,” by Greek writer Gianni Skaragas, which evokes the waves of humanity breaking on Europe’s doorstep (page 56). The islanders in Skaragas’s story put themselves “in God’s place, trying to save what is most worth saving,” but the capsized boats they find in the water are empty, with no sign of survivors. When the narrator’s father, an Orthodox priest, dreams of being pulled from the water by an unknown hand, he hears a voice, no more than a whisper, say, “This is your new land now.” For the waves of migrants making similar journeys in 2017, Skaragas wonders, who will tell their story? Who will “bear the listening”?

Yet the story of the European refugee crisis is only part of the overall migration narrative. Refugees International estimates that currently 65 million people worldwide have been displaced, the highest number since World War II. Still, some 90 percent of the world’s refugees—from places like South Sudan, Burma, Colombia, and Sri Lanka—remain in their own regions and are hosted by developing countries, according to unhcr high commissioner Filippo Grandi. A remarkable new visualization by the create Lab at Carnegie Mellon shows the flow of refugees around the world in the past fifteen years.

Grandi wrote the foreword to an urgent new book by Giles Duley, I Can Only Tell You What My Eyes See (forthcoming in the US from Saqi Books in October), that features more than 150 photographs of refugees, ranging in age from two to ninety, taken in 2015–2016. Duley’s photo-narrative begins on the island of Lesbos, then documents migrants’ journeys through Macedonia, Germany, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq. “Providing protection to people seeking refuge,” writes Grandi, is one of the “foundational values” of postwar Europe.

At the Summit for Refugees and Migrants in September 2016, the UN General Assembly adopted the New York Declaration, which “expresses the political will of world leaders to save lives, protect rights and share responsibility on a global scale,” with the goal of achieving “a more equitable sharing of the burden and responsibility for hosting and supporting the world’s refugees by adopting a global compact” by 2018. Yet in summer 2017, as thousands of new refugees uproot their lives every week, a global compact on the far horizon must seem like empty talk.

In the meantime, writers and artists help us see the individuals and deeply human stories behind the policies and statistics. “There is no such thing as truth in photography,” writes Duley, but as a photographer bearing witness to “humanity . . . laid bare on the shores of Europe,” the truth value of such a documentary impulse is inestimable. For the writers gathered in the current issue, “lives interrupted” are not about daily inconveniences like getting stuck in traffic or misplacing our phones. The interruptions at stake here are states of emergency in migrants’ lives, existential turning points with life-or-death consequences.

Daniel Simon