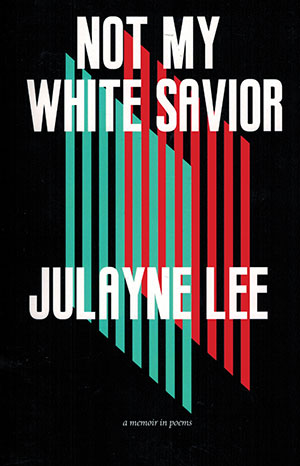

Not My White Savior by Julayne Lee

Los Angeles. Rare Bird Books. 2018. 128 pages.

Los Angeles. Rare Bird Books. 2018. 128 pages.

Julayne Lee’s debut poetry collection is a tightrope walk between rage and respect. Not My White Savior begins with an introduction that helps readers contextualize the work, in which Lee declares that she is one of two hundred thousand Koreans adopted because of the Korean War. “We are living evidence of a history that has far too often been romanticized, glamorized, and inaccurately and incomprehensively documented.” The book is divided into five sections, each challenging a different facet of traditional adoption narratives through the lens of Lee’s personal experience to serve as a memoir in verse.

In an early poem, readers can follow Lee’s evolution from someone who created her own “Asian American History 101” course through the work of other poets—with nods to I Was Born with 2 Tongues, Ed Bok Lee, David Mura, and more—and learned to find strength in her own identity in poems such as “My Ancestors Were Royalty.” Metaphors such as the body as the DMZ, divided and at war like the North and South, enrich and complicate poems that tackle whiteness and cultural appropriation. In one poem, she compares the adoption process to selecting a houseplant that complements the family’s lifestyle. In another, she laments the loss of such basic personal details as her true birthday and the Korean language fitting comfortably on her tongue.

Many strong poems are those that directly address perpetrators of trauma. In “Dear White Family,” Lee writes, “I could never be white enough for you,” followed closely by a poem for her birth, foster, and adoptive mothers that somehow holds the full spectrum of emotions children can feel toward their mothers. Still other poems honor the history of suicide among adoptees through elegiac solidarity: “we expect death / for every life taken by suicide / how many more considered / this journey / from this life we cannot escape?”

Not My White Savior is an unflinching poetry collection that rages against the injustices suffered in silence by the adoptee community and, for many years to come, will serve as both beacon and megaphone for those two hundred thousand forgotten children scattered across the globe.

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello

Miami, Florida