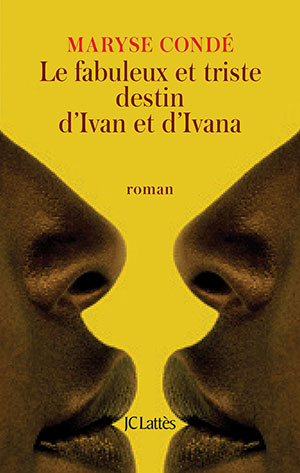

Le Fabuleux et Triste Destin d’Ivan et Ivana by Maryse Condé

Paris. Lattès. 2017. 365 pages.

Paris. Lattès. 2017. 365 pages.

Ivan and Ivana, whose intertwined destinies structure this novel, are twins born in Guadeloupe. The brother and sister grow up in difficult circumstances: their mother is poor, and their father returned to his native Mali before their birth. Throughout their lives, Ivana and Ivan share an exceptionally strong emotional bond, even for twins, to such an extent that they are terrified of their potentially incestuous desires. Eventually their “fabulous and sad destiny” will lead them to go live in Mali and later in Paris, where their paths will diverge widely, with tragic consequences.

Maryse Condé addresses very contemporary issues in her latest novel: racism, jihadi terrorism, political corruption and violence, economic inequality in Guadeloupe and metropolitan France, globalization and immigration, etc. As relative innocents in a depraved world, Ivan and Ivana provide an unlikely and contrastive viewpoint on the increasingly sordid events they witness or endure. Their initial minor differences as children (Ivana is a better student than Ivan) gradually turn into dramatically different life choices. Ivana, in keeping with her youthful altruism and enthusiasm, chooses to enter the police academy in Paris. Ivan, increasingly alienated by the various forms of exploitation that he encounters, chooses the nihilistic path of radicalization and terrorism. Readers will find parallels with the 2015–2016 wave of terrorist attacks in France. Ivan and Ivana, the twins who can neither live apart nor consummate their incestuous love, will become perpetrators as well as victims in that wave of mass slaughter.

In the course of the narrative, Condé alludes to some of her previous novels, including Ségou (1984–85). The characters Ivan and Ivana, through their upbringing in Condé’s native Guadeloupe, and later through their travels to Africa and France, provide echoes of the author’s own life and literary career (see WLT, Autumn 1993). Unfortunately, this may be Condé’s last novel, due to her state of health. It is therefore tempting to see it as a recapitulation of her vast novelistic oeuvre. The fact that the narration is sometimes punctuated by observations originating from what appears to be the author’s voice adds to this impression. For example, the last page features comments directed at readers: “you find this character to be less than convincing” and “what you find most shocking.” At once playful and directive, these instances of metacommentary ask readers to reconsider their initial reading.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University