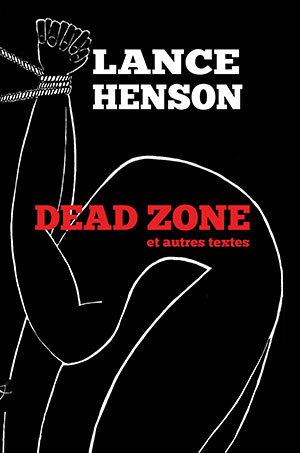

DEAD ZONE: Zone morte et autres textes by Lance Henson

Lafarre, France. Les éditions de la Tortue. 2018. 119 pages.

Lafarre, France. Les éditions de la Tortue. 2018. 119 pages.

Born in 1944 in Washington, DC, poet and playwright Lance Henson grew up in Calumet, Oklahoma, with his traditional Tsis-tsis-tas (Southern Cheyenne) grandparents. Henson has long been both an internationally known and a prolific writer, authoring over thirty volumes, translated into twenty-five languages. A member of both the Native American Church (peyote religion) and the Cheyenne Hotamémâsêhao’o (Dog Soldier society), Henson served as a Marine during Vietnam. Being both a peyote man and a warrior give him responsibilities, according to Cheyenne customs, to protect and to pray. In this new volume, his poems, his songs, use words with those aims. In doing so, he acts much like the water protectors at Standing Rock to whom he dedicates “the river sings.”

DEAD ZONE: Zone morte et autres textes is mostly a bilingual volume in French and English; like his other works, however, it includes a good portion of the Tsis-tsis-tas language as well. The volume is divided into two sections: “songs of two worlds” and “the dead zone.” The book’s epigraph—in Henson’s handwriting, then in English, and finally in French—reads: “We are not human beings / on a spiritual journey / we are spiritual beings / on a human journey,” a quote often attributed to French Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The first words of a poem, however, are in Tsis-tsis-tas and center the volume at the point where we currently are in the human journey: “mapi / mapi / dosah / dosah,” which translates to “water, water, where, where.” Written, as the title says, “for the dine,” the poem refers to the water crisis the Diné (Navajo) people are experiencing because of contamination, shortages, and lack of access but also refers to the greatest immediate challenge for all humans in the Anthropocene era, continued supply of this life-giving resource. The juxtaposition here—of the French audience, the Cheyenne poet with French heritage, and the Diné to whom the poem is written—reminds us of our shared humanity and common fate. Henson calls America to a spiritual accounting for what has been done to the physical world and the spirits humaning within it.

As Robert Berner noted (see WLT, Summer 1990, 418–21), Henson’s free-verse poetry is strictly minimalist, imagistic, and has very little, if any, punctuation or capitalization, but its intensely electrifying sparseness intimately connect the humans in the reading audience to the natural world of wind, wet leaves, winter, wolves, crows, tornadoes, rivers, and plains as the Guarani Indians to whom one poem is dedicated are connected to theirs. These poems guide us through a world of burning forests and “burning villages,” the genocide and environmental devastation brought by settler-colonialism and global corporatization, toward spiritual evolution. In DEAD ZONE, Henson is one of the “seers” from his poem of that title, who are “singing themselves from the misery / of the world . . . / singing toward the sleeping ones / who are yet to awaken.” (Author note: Throughout, I, like his translators, respect Henson’s choices on capitalization. Henson’s use of capitalization in his titles has varied over the years.)

Kimberly Wieser

University of Oklahoma