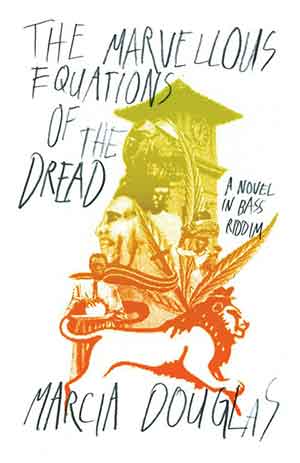

The Marvellous Equations of the Dread: A Novel in Bass Riddim by Marcia Douglas

New York. New Directions. 2018 (©2016). 304 pages.

New York. New Directions. 2018 (©2016). 304 pages.

Marcia Douglas, born in the UK and raised in Jamaica, is a novelist and poet who currently teaches creative writing and Caribbean literature at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Her novel The Marvellous Equations of the Dread was longlisted for the 2016 Republic of Consciousness Prize and the 2017 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. In addition to writing, she performs a one-woman show, Natural Herstory. Like her one-woman show, there is something about The Marvellous Equations that is suggestive of the ancient art of the choreopoem. The characters provide recitations, dance, and perform their stories in the novel, symbolic of the lives that they led while alive. They defend their actions or lament them as acts of redemption, and what better way to redeem than to perform acts to repair society.

The Marvellous Equations of the Dread is a richly textured novel, employing vibrant dialogue and lyrical narration. It courts the mystical as well as the reasoning of the Rastas. The ancestors are awakened and called to help the people of Jamaica. This is the story of Robert Nesta Marley, Haile Selassie, Marcus Garvey, their loves, Jamaica past and present, and of the Rastas, among others. The work gives a whole new rendering to John Berger’s notion that “Never again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one.” It takes several generations to advance this story with some pretty amazing characters along the way.

The center of the story revolves a reincarnated Bob Marley and his love for Leenah, the deaf daughter of parents who are persecuted for being Rastafarian. Marley is called back to Jamaica as Fall-down man, a homeless person who sleeps in a clock tower and who is presumed to be mad. Neither his wife nor his lawyer can recognize his spirit encased in the body of a fallen angel. He is called back to complete a mission but is unable to initially recall that mission. Unlike their other duppies that inhabit the clock tower and the hills, he is posited as something of a savior: the prophet who returns to save his people and can walk among them. This embrace of the rational and nonrational is a very African way of experiencing the world. He sees the chaos of modern Jamaica and tries to direct the people to Zion—which by turns we learn is not external to humans, rather inside their hearts.

In a poetic-like rendering, the narrator recounts a sampling of the island’s tribulations: “A woman at the bus stop has a gun in her brassiere / the light turns red and / a grandmother dreams of Zion-high / a schoolgirl sucks salt-water tears / pigeons pick mould from a piece of dry bread / green mangos fall before they can ripe / sorry, no jobs / the baby’s milk spoils in the hot sun / the clouds over Kingston heavy with cares-of-life tears / Public Works on strike / weevils in the flour / an eviction notice nailed to the door / rotten chicken-back in the market / sorry, no job / the children’s coffins are made of pine / sorry no / the goat tied to the ackee tree cannot bleat / sorry. The people are vexed with sufferation.”

So how does a once-famous, deceased musician lead his people to Zion? He speaks through the bass riddim of the Jamaican landscape. This work may easily be classified as a neoresistance narrative. It harkens back to the past of slavery, oppression, and violence to account for the situation in Jamaica today. The ancestors’ rebellious acts and products must come to bear in order to defeat the enemy of violence, poverty, and hatred. By turns the novel reveals that the solution must begin with the children, and music can be a cure for the malaise.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University