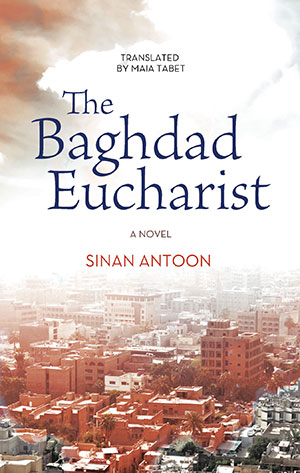

The Baghdad Eucharist by Sinan Antoon

Cairo. Hoopoe / American University in Cairo Press. 2017. 129 pages.

Cairo. Hoopoe / American University in Cairo Press. 2017. 129 pages.

Sinan Antoon’s novel, Baghdad Eucharist, translated by Maia Tabet, originally published in Arabic by Al-Kamel Publishers and shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2013, is a visceral yet poetic novel about the Iraqi diaspora. Born in Iraq, Antoon moved to the United States in 1991 and has achieved recognition as a poet, novelist, and translator. Given the turbulent state of many countries in the Middle East and the increase in terror attacks throughout the world, Antoon’s novel touches a raw nerve. Antoon describes the memories of one family and shows how the entire fabric of society is destroyed when families are forced to flee, are killed by sectarian violence, or might simply disappear, never to be heard from again.

The entire novel takes place in Baghdad in the course of one day, much like One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Seventy-year-old Uncle Youssef, however, is not serving time in the Soviet Gulag but is living under siege in violent Baghdad, a prisoner of his past. Unlucky in love—with a cousin who married someone else, and a Muslim colleague who could not marry him because of the religious difference—the sensitive Uncle Youssef lives in a big house, alone. He spends much of his time reminiscing about family members and friends who have died or immigrated.

The perspective of an older generation contrasts with the point of view of Maha, still in her twenties and hoping for a better future after losing a baby. She is training to be a doctor and plans to immigrate to Canada with her husband, Luay. After a series of attacks on Christians in her neighborhood, she has come to live with Uncle Youssef because this part of Baghdad is supposed to be safer. While Maha waits for her papers to Canada, she finds a Facebook page called “Beautiful Iraq.” The collective memory of the Iraqi diaspora is not monolithic—there are many versions of the past, depending on who you are:

Some of them considered the Baath Party’s coming to power and the brutal way Abdel-Karim Qasim was put to death as the end of the “good” times. Others felt Saddam’s accession to the presidency in 1979 was the beginning of the end. The good times stretched to 1991 for yet others who regarded the sanctions as the turning point for Iraq, and then there were some who considered 2003 the end. Most were nostalgic about the time of the monarchy and they post photographs of the former royal family, the subtext being that their brutal execution in the military coup was the beginning of the descent into the abyss. . . . Hadn’t Assyrians been killed even during the halcyon days of royal rule? Hadn’t Iraqi Jews effectively been expelled from their country overnight after being collectively dispossessed? Hadn’t poverty been widespread? And the regimes that followed—weren’t they soaked in the blood of the Kurds and the Shiites who were slaughtered and thrown into mass graves?

“The good old days” of Iraq never existed. However, there is no simple view of the future, either. With the globalization of terror networks and the spread of propaganda through the Internet, sectarian violence is no longer contained either by locale, country, or nationality.

When tragedy strikes near the end of the novel, both Uncle Youssef and Maha offer their desperate prayers to Maryam, or Mary. The original title of the novel, Oh Mary in Arabic, is a more fitting, evocative title for this poignant novel.

Gretchen McCullough

American University in Cairo