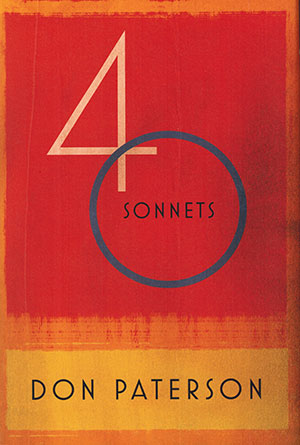

40 Sonnets by Don Paterson

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017. 64 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017. 64 pages.

The sonnet carries more freight than any other form in the English tradition, which it entered early in the sixteenth century through Thomas Wyatt’s loose translations of Petrarch. With the form came a host of conventions: unrequited love, cruel beauty, the lovers’ paradox. The greatest sonneteers, however, have shown as much ingenuity in subverting the form as in meeting its formal and thematic demands. Early on, the Earl of Surrey altered the Italianate rhyme scheme to be suitable for English, creating what is, unfairly, known as the “Shakespearean sonnet.” After half a century of lovers’ eyes shining like the sun, Shakespeare frankly declared that his mistress’s “eyes are nothing like the sun.” Early in the seventeenth century, John Donne turned the sonnet’s erotic energies into devotional verse, and, at century’s end, Milton made the sonnet political. In the twentieth century, Robert Lowell jettisoned the form’s ornate rhyme for his confessional sonnets, while Ted Berrigan turned sonnets into an avant-garde game of cut and paste. Even with this history weighing on the project, Scottish poet Don Paterson makes the form fresh and interesting in 40 Sonnets.

Paterson writes some formally strict sonnets, but he also isn’t afraid to jazz around. “Séance,” for instance, is fourteen lines of Ouija board gibberish: “Speke. – see sskseek[.]” “Shutter” reduces the standard sonnet’s iambic pentameter to a few syllables per line—“As she slept / late / below”—but brings to the surface the sonnet’s barely submerged eroticism: “the naked / skylight / he lapped / her breast[.]” Paterson uses blank verse in “The Foot” to tell a heartbreaking story of violence in Gaza. Some of the sonnets seem intensely personal, like “The Roundabout,” in which, addressing two children, he describes a day that was “our first out / after me and your mother.” It is hard to tell if the “after” demarcates a marriage or a divorce, and this reticence makes the gesture seem all the more intimate, a technique used throughout. Yet another poem imagines what it feels like to be a wave, and yet another attempts to poetically embody the curmudgeonly TV doctor “House.”

Out of a single form, Paterson makes a great variety of poetic experiences. Much of the fun in 40 Sonnets is in watching how the form shifts from poem to poem and in watching how Paterson’s various approaches interact with the sonnet’s illustrious history.

Benjamin Myers

Oklahoma Baptist University