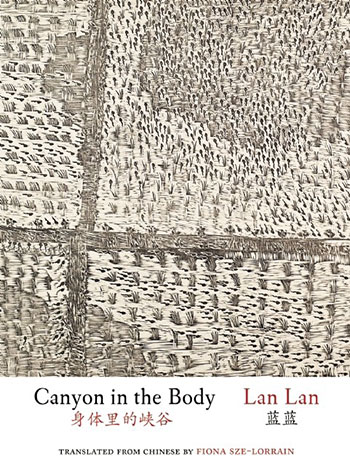

Canyon in the Body by Lan Lan

Fiona Sze-Lorrain, tr. Brookline, Massachusetts / Hong Kong. Zephyr Press & The Chinese University Press. 2014. ISBN 9781938890017

Lan Lan’s poetry in Chinese is as distinct and immediately recognizable as your mother’s voice (see WLT, March 2015, 19). Her language is cool and clean and strong, like glacial ice. Her messages are intimate without being sentimental, bearing the sincerity of secrets. Her inimitable quality is the result of an adherence to simplicity and sympathy, as her poems speak directly to the reader and use white space as consciously as they do words.

Lan Lan’s poetry in Chinese is as distinct and immediately recognizable as your mother’s voice (see WLT, March 2015, 19). Her language is cool and clean and strong, like glacial ice. Her messages are intimate without being sentimental, bearing the sincerity of secrets. Her inimitable quality is the result of an adherence to simplicity and sympathy, as her poems speak directly to the reader and use white space as consciously as they do words.

Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s English translations, presented here alongside the source texts, are all this and more—sometimes a little too much more. They are crafted out of a vivid, resonant, yet also malleable and cosmopolitan English, which takes full advantage of its own phonetic and rhythmic resources yet also borrows directly from French, say, when Sze-Lorrain finds it appropriate. While her idiom is restricted in other dimensions, the refusal to limit it by orienting it toward an imagined cultural center gives it flexibility and power. The best translations in this book are made from exactly this sort of language. For example, two stanzas from “Lost”: “He has the shape of leaves and clouds / In his footprint / the shape of seasons reflected in a puddle // Sometimes, someone will walk n / a badly inflamed knee joint – / to the suburbs ear an old rail / above the overwhelmed daisy fleabanes / to meet another him.” Or another example from the next poem, “Wind”: “an arm face forest / of dandelion pistils in the eyes. / Blows away the canyon in his body. / An empty house. Silent voices / left on the wall for years.”

Passages like these accurately represent Lan Lan’s voice and communicate her primary concerns. Unfortunately, the translations as a whole are inconsistent; while some are brilliant, others are surprisingly awkward, and a great number are overwritten. Lan Lan is not an academic poet; her language is quotidian, her tone utterly unpretentious. But Sze-Lorrain, whose own individual aesthetic is so strong, will not let her go. Small words like dongxi 东&و (stuff) are translated away; the very simple title zhenshi /u实 (truth/true) becomes “Vérité”; the word zoudong (+动 (to walk around) becomes “ambulate.” Translations of “Wild Sunflower,” “An Ear of Grain,” and other poems, which are written in very straightforward Chinese, employ inverted syntax and self-consciously poetic vocabulary. They are beautiful choices that overrule the source text instead of cooperating with it. In addition, several translations toward the book’s end read like drafts. Passages like “meant for two hands’ fiery flames / it is now growing fungi absurdly” or “On some empty land in the woods I step on its edge / and dream of them. / If I forget these, I’d die out / suddenly” suggest hurried translation or scanty editing.

The majority of the translations in this volume are both artistically accomplished and reflective of the source texts. Yet there are too many instances in which the translator steps in front of the author instead of standing beside her. Readers expect good translations to stand independently in their own language, of course; should we not expect them to be co-creative as well?

Canaan Morse

Manchester, Maine