(books read when drunk)

Avid reader Andor Femin and the narrator of this flash fiction don’t always see eye to eye, but their observations about reading are always amusing.

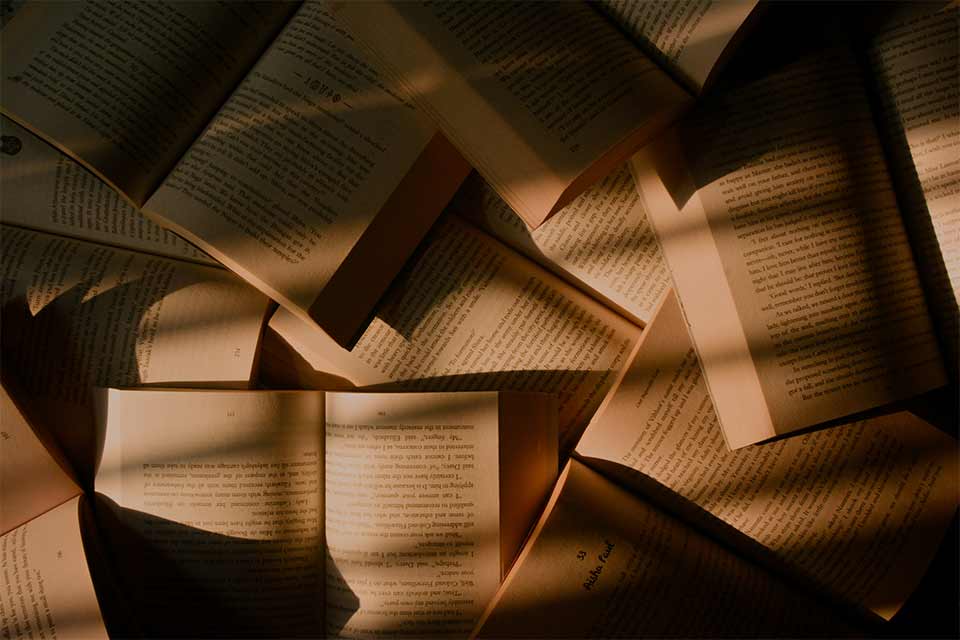

Andor Femin is an avid reader. He particularly likes thick, action-packed hardcover books that leave a slow-to-fade, bloodless white strip between index finger and thumb. But he also likes books of poetry, volumes that popularize science, the occasional florilegium, and it can happen that he has two books on the go at the same time. While drinking. Andor Femin doesn’t use bookmarks, so he would leave books lying about like others leave soiled clothes, in the most indecent positions: with their printed pages folded together, on freshly washed pillowcases, on top of the breadbasket, in the close vicinity of groceries. On the other hand, Andor Femin never reads in bed, in the bathtub, or on the toilet. For reading, you need silence and tranquility—and time, of course—but Andor Femin insists that it’s precisely people who read that create silence around themselves. We don’t see eye to eye in everything to do with reading, and I am a little bored when Andor Femin’s small, round head disappears for hours behind a book, but I like that bloodless strip that remains on his hand for a few minutes. Although I rarely have the occasion to pick up a book—the moment I open one, my relatives flock around me to cast a shadow over the pages with their freshly coiffed hair, flimsy robes, hyperactive limbs—I do like imagining myself in the company of people who read. Their silence soothes me. I see them with their fists placed on the even-numbered pages, relaxing and opening into their palms. I see their fingers playing with the edge of the page, unwittingly teasing the corners as they read, then starting to turn the page prematurely while the final lines are still being read. For it is as if two people dwell within them: a reader and a page-turner, whose interests do not completely overlap. I see before me how their gaze—like the gaze of Andor Femin—runs in a straight line from letter to letter, from line to line, and it occurs to me that there is nothing in the world that moves ahead at such a steady pace, yet which nevertheless keeps cumulating the sum total of its progress from such utterly insignificant items. Andor Femin gives me an appalled look when he hears me talking like this. Although I don’t have time to read, and the endbands on the spines hurt my skin—chafed by all the washing-up—I like contemplating the profusion of letters from afar; I like peering into the books from above Andor Femin’s broad, dandruffy shoulders, just as the busyness of ants or wasps is more interesting when seen from a distance, when they can’t sting or climb on us or force us to extinguish their lives in self-defense. And anyway, I say, everything of which there is a lot is beautiful. Of course, Andor Femin doesn’t reflect too much on reading, he just reads. While drinking. Sometimes he makes me sit down in front of a cookbook, or holds a magazine under my nose, so that I will leave him alone at last. Once I nagged him until he told me that what he reads sounds inside his head in a kind of voiceless, genderless tone—something closest to a whisper. A slow, leisurely whisper which, Andor Femin went on, is not that of the writer and not of his parents, but also not his own. Does it then mean that people with a speech defect don’t read with a speech defect, I asked Andor Femin, to whom this thought has never before occurred, obviously. Perhaps that’s why he lost his patience with me; at all events, he snapped shut the hardcover history atlas and, grasping it with both hands, brought it down rudely on my head. I slunk off. Be that as it may, it would be impossible for me to hear any kind of whisper with the buzzing and whirring of all my household gadgets, acquired and inherited, and Andor Femin knows that too. One who drinks a lot while reading, on the other hand, will hardly be able to distinguish the inebriation caused by the whisper from the inebriation caused by wine; small wonder then that from the Strudlhof Steps, as Andor Femin puts it, he will not remember the steps, nor from Child Psychology, the development of the concept of numbers, nor from War and Peace anything about peace. I have witnessed on more than one occasion how Andor Femin is overcome by sleep while he is reading. It starts with his leafing backward more than forward; later his elongated—exclamation-mark-shaped—fingers go limp, until his head too droops forward, his glasses slip down to the tip of his nose, and he starts breathing with a wee snore to the rhythm of compound coordinate clauses. In such moments, I sneak over to the armchair, pull the book from his hands, and, before closing it, drop a pencil between the pages. Later, when Andor Femin starts awake at night, I see him to his bed. If he is still not completely woken up, he accuses me—looking me up and down with suspicion and, of course, asking for the book to be placed within reach—of not having a reader and a page-turner dwelling within me. In his opinion, I am merely a page-turner.

Translation from the Hungarian

Editorial note: From Mondatok a csodálkozásról (Magvető, 2021), translated as Sentences on Wonderment by Erika Mihálycsa with Peter Sherwood.