Dustsceawung

Our columnist looks back through the centuries to rekindle our fascination with dust. Using the word itself as her point of departure, she questions what our culture values enough to preserve and how we value things by paying attention to them.

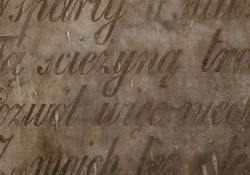

The beguiling Old English word dustsceawung is typically translated as “the contemplation of dust,” although its full potential is certainly far richer and more complex than what those few words convey. To take a glance at some of this word’s depths, at Guernica magazine, the poet Maya C. Popa wrote that it means “the acknowledgment of dust as once having been other things, living beings or civilizations past,” adding that “dust requires us to confront our own transience and eventual anonymity, and doing so demands a flexible, inventive use of language.” The nonfiction writer Adam Nicolson poetically defined it as “the daydream of a mind strung between past and present.”

To our modern ears, a word that is all about staring at dust might sound hopelessly strange and archaic. Perhaps this is why, for poet Jane Zwart, who wrote a poem entitled “Dustsceawung,” the word is evidence of just how much language has managed to name—if a word like this exists, then can anything not have a name? As she told Franchesca Viaud, who interviewed her for the Massachusetts Review:

That is the kind of amazing lexical gem that makes me think, for a second, that there’s a word for every single thing. I know that’s not really true . . . [b]ut it is true that there are names for a staggering number of things: for tailors’ scraps (carbage!), for the thin ring of light that an eclipse leaks (halation!), for the seed pods that helicopter down from maples (samaras!). I spend a lot of time, in fact, looking for the names of such things when I’m writing. . . . I want my students to get into that habit, too. I want them to understand that so much of language springs just from someone paying exquisite attention to something and wanting to do that something.

It is strange to think that people living in the medieval era had already grown so comfortable with the way that dust forms the common factor of all things that they had a word for it, and stranger still to think that at some point English lost that word and we no longer have it—that we must look back through the centuries to rekindle our fascination with dust. Dustsceawung offers an opportunity to consider all the notions our language has chosen to keep, and which ones it has let fall by the wayside. It is an entry point to questions about what our culture values enough to preserve and what we see the value in paying attention to.

Dustsceawung offers an opportunity to consider all of the notions our language has chosen to keep, and which ones it has let fall by the wayside.

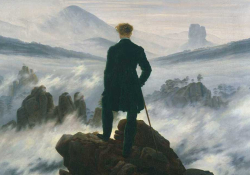

Let’s pay a little more attention to dust for a moment. As the South Korean scholar and translator Sung-Il Lee puts it in an essay, the core of the concept of dustsceawung is “the thought that all existing things, including men and women, will eventually turn into dust.” Stop and think about that (it may be an uncomfortable thought). This cosmic word tells us that, on a long enough timescale, everything will turn into dust, and dust will turn into everything. It’s downright terrifying to imagine it, in that way the Borgesian can sometimes have of bending toward horror.

It’s impossible to know just what thoughts and connotations dustsceawung would have brought to mind to a speaker of Old English, but Lee instructs us that it was associated with themes of mutability, transience, decay, and ruins. In our own time, the invocation of dust conjures up very different images—those of the cosmos: the massive, beautiful nebulae that stars are born in, the disc of dust that our solar system accreted from, the dust clouds that turn into the spectacular vision of Saturn’s rings, and the stardust that emerged from stellar explosions, forming the higher elements without which development of complex life forms would be impossible. Dust connects some of the tiniest objects in our universe to some of the largest.

Beyond being cosmic, dust is also a word with strong religious connotations in the Western world—for instance, it will almost certainly make one think of the funereal oration from the Book of Common Prayer: “We therefore commit this body to the ground, earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life.” This prayer in fact references a quote from Genesis, spoken when Adam and Eve are dismissed from the Garden of Eden: “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.” The implication of both quotes is that of humility in the face of our materiality, of being ground into the tiniest, most modest of particles by the forces of death and disintegration.

Even if dustsceawung comes off as disconcerting, or maybe even slightly morbid, it also seems perfectly appropriate to our era.

Even if this word comes off as disconcerting, or maybe even slightly morbid, it also seems perfectly appropriate to our era, as obsessed as we are with notions of decay, as aware as we are that cosmologists predict the universe will eventually collapse in on itself down to nothingness, and then possibly resurrect back into existence. To return to Popa, she makes the case that dustsceawung is a truly modern word:

The speculative insight and human anxiety at the heart of dustsceawung should, to my mind, make the word a strong contender for modern adoption. The effort to accept dust as our fate takes a whole life, and all of literature. We wait for the dust to settle, but it never does.

Unsurprisingly, artists—experts as they are in looking back to look forward—have seen the value in the contemplation of dust. A characteristic 1920 collaboration between Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp saw Ray travel to Duchamp’s New York studio, where he photographed the dunes of dust that had collected on Duchamp’s sculpture The Large Glass over the course of a year. The photograph, called “Dust Breeding,” was made via an extremely long two-hour exposure and has gone on to become a celebrated piece of modernist art. The art curator David Campany, in fact, organized a whole exhibition of dust-themed art in its honor; in an essay, he noted how dust transformed the medium of photography from something that represented the epitome of the quick, mechanical, and contemporary to something that leaned backward to the archaic, the primitive:

“Dust Breeding” refuted the instantaneous. It denied the quick snap of the shutter that came to dominate the medium’s relation to modern time. Its exposure was made over a leisurely lunch, not in the blinking of an eye. Its subject matter is the epitome of all that is slow. Today photography’s romance with speed is all but over. The “decisive moment,” the art of the caught photograph, seems like a distant chapter. Where photography was once the medium of moments, it now appears in many ways to be a deliberating, forensic medium of traces. This may sound like an end but it could be a new beginning. Photography is coming to terms with its relative primitivism.

Perhaps there is something of dustsceawung that reaches us back toward the primitive parts of our psyche. To be enamored of dust, after all, sounds horribly unsophisticated, almost doltish. But perhaps the more anti-intellectual thing is to dismiss it.

Perhaps there is something of dustsceawung that reaches us back toward the primitive parts of our psyche.

In a wide-ranging, fascinating essay on the intersections of dust and art, the musician and researcher Andreas Rauh considers that noticing dust isn’t so much a question of whether dust is in our vicinity—it surely is there (it is always with us). The real question is if we choose to pay attention to it:

The specific composition of the dust you have collected is also random, representing an unplanned moment of collection, a consideration of something materially and apparently inconspicuous in the current in-between of arising and vanishing. This characteristic is shared by dust with the atmospheres that surround us. They are present, even if one does not pay attention. And if one pays attention to it, then it is always and everywhere, can become a guide to action, and can be influential.

Whether it is a substance that clogs our pores and makes us sneeze, or a building block of structures on a cosmic scale, we notice dust only insofar as we choose to do so. This property of dust is also a fitting summation of what language does—it draws our attention to some things while placing other things outside the range of our attention. It all depends on what has been named, and knowing the names for those things.

Oakland, California