Ruins

“Ruins give us this beautiful idea,” writes the author, “that you could make something, something wonderful and strange, as pleasing as you could, imbuing it with something of yourself.” Yet even the self, subject to time, must evanesce.

I.

Today the wind churns up, as if on some terrible errand of vengeance; trees uprooted all over the city, parks closed for damage assessment. But I’m out in the weather, on a day trip to a site that was once an ancient port city at the mouth of the river, where women had their ecstatic visions, where pirates kidnapped senators, where residents and visitors thronged the theater and the public baths. The port city now mostly foundations and rubble, arrayed in the rough shapes of houses and apartments and shops and baths and temples, columns jutting up now and then like the first weeds growing back after a fire. Acres of ruins sit exposed to the elements, cragging and crumbling even further into ruin.

I roam among the cypresses and umbrella pines and the ancient, weathered stones, placed there by the wealthy and the ambitious for purposes, noble and ignoble, that have always moved men to build things, and still do. Here a headless statue, there fragments of frescoes—one depicting a pair of human legs, painted in the faded pastels of time passing. Marvelous mosaics appear underfoot, naked men posed in warlike stances and holding spears, horses with the hindquarters of a serpent, fanciful fish, leafy patterns.

In moments like this, when coming upon a fragment of a fresco with a pair of legs, legs not unlike my own, I feel a sense of astonished recognition, though of what, or whom, I’m not sure. Maybe it’s just the dumb luck of those legs having survived. And the tenaciousness of art, which is moving in part because utterly useless—against time, against loss. Moving also because nonetheless hopeful, a recognition of our shared humanity, our shared mortality. Those ancient legs, which seem capable of stepping off that chunk of wall, so alive do they seem.

The tenaciousness of art is moving in part because utterly useless—against time, against loss.

Each discovery miraculous, these ancient hints of human making, the impulse to beautify, to decorate, to tell stories. We are gifted with it, compelled by it, this impulse, and we feel that kinship of makers, which easily stretches its arm across centuries and oceans, and in that stretching allows us an acquaintance, as if we were standing across from each other and shaking hands. We need know nothing about the artist’s particulars—those details denied us by the erasures of time, even if we sought them—to feel the thrill of connection. We need know nothing at all, not even the artist’s name.

The ruins give us this beautiful idea: that you could make something, something wonderful and strange, as pleasing as you could, imbuing it with something of yourself. And if you managed to send it out into the world and it managed to last, even as a ruin, it could speak to anyone who encountered it, speak for you long after you were gone, perhaps for thousands of years—that is, if the human race can survive its own stupidities past the next generation.

II.

I’ve discovered I prefer ruins to intact new things. Not to live in, of course, but to visit, to explore. The lure of the abandoned and the decrepit, the cracked vestiges of things formerly solid, have a pull on me; their ruination feels almost soothing, perhaps because among their slow erasure I feel in good company, my own erasure, the erasure of so many species, including the human species, such a constant concern these days. Also, I quite like the amorphous thingness of a ruin, which no longer can serve any practical function and therefore passes into the realm of being for its own sake, enduring and deteriorating both.

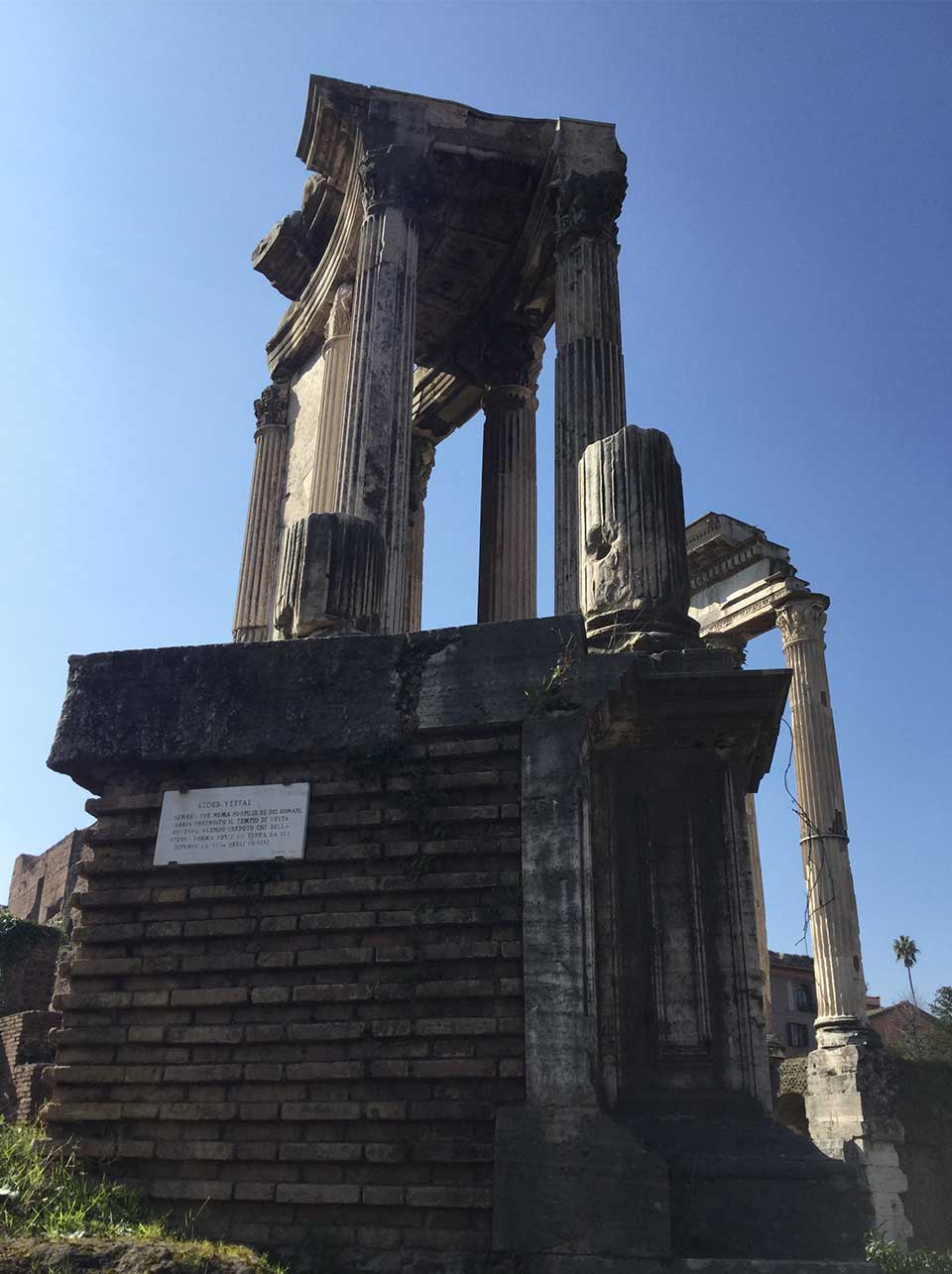

In this spirit I join an excursion to a famous archaeological site in the center of this city famous for its archaeological sites. The outing is led by an internationally known classicist, a contrarian and provocateur who is nonetheless unfailingly polite, civilized in the manner of many of the repressed citizens of her nation of origin. I’m thrilled. I’ve walked past this famous site so many times with a single, dim thought: Wow, a bunch of old stuff. Wonder what it is? Now, at last, the classicist would provide the multiple, enlightening answers to this single, dim thought. It would all make sense, and I could then have many richly intelligent thoughts about the old stuff.

Well, imagine my confusion when the famous classicist starts in on how famously frustrating this famous archaeological site is, how careless and messy and largely unintelligible. This while we’re standing at the entrance and haven’t even encountered any of the old stuff. Once we step inside, it only gets worse; the famous classicist questions practically every fact, the word “fact” crumbling in the tight grip of her skeptical, probing intelligence. At a certain point she instructs us to insert the word “possibly” before every verb she utters, to save herself the trouble of having to repeat it ad nauseam. In essence, she can assert very few facts for certain, almost all of these general. “We do know that the Temple of —— stood here,” for example, but how to account for all the other chunks of old stuff lying around, she has no clue.

For well over two hours we troop through the site in the wake of the famous classicist’s withering skepticism, the piles of old stuff making not more sense, as I assumed, but less, the classicist repeating like a mantra the one fact she can confidently put forward: that we really have very little idea of what we’re looking at as we march through the ruins. We come upon a house that purportedly sheltered a cadre of virgins chosen to guard a temple for thirty years, after which each was free to marry, though these marriages, according to the classicist, usually came to a tragic end. As we contemplate the house from its courtyard, which is adorned with statues of robed women—the virgins, presumably, most de-limbed and beheaded by the elements—the classicist gleefully points out that the statues and their bases hail from totally different eras. Heaven only knows where these statues originally stood, where they were from, and who decided to put them where they were—all questions with no answers, the whole thing a fiction, a fantasy.

Yes, the stuff was old, or at least most of it was, although there had been attempts at restoration using newer materials. However, the new materials were not labeled as new to distinguish them from the genuinely old. No, old and new mingled freely, with no perceivable concern for historical rigor or accuracy. So that at any given moment one had no idea of what era one was encountering, historically speaking, and if one relied on the sparse documentation available, one was still very much in the dark. Much of the signage makes assertions that couldn’t possibly be verified, the classicist grimly asserts, so that in the end I leave this famous site with my single dim thought unexpectedly, even disappointingly confirmed: Wow, a bunch of old stuff. We have no idea what it is.

And it’s not just this site, as the classicist informs me days later over drinks. It’s every site, including the ancient port city, its ruined acres cleaned up in the earlier part of last century, when this country’s rabid fascist wanted to make another statement in support of his own greatness, reflected in the city’s monuments and artifacts. He galvanized his team of patriotic archaeologists to do his bidding and spruce up the ancient port city. So again, a place with a lot of thrillingly old stuff, piles of it somewhat randomly stuck together to give an impression of wholeness. Though the entire city was irredeemably fragmentary, like any ruin.

The fragmentary nature of a ruin invariably compels us to imagine the ruin in its former glory. Humans always standing just at the edges of imagination—at the farthest reaches of which lie not only the unimaginable but, better still, the possibly real—with the fervent desire not merely to imagine but to see. If only we could see, the logic goes, then the thing imagined could be real. Once we hurl ourselves into creating that reality, we begin the process of reconstruction, which inscribes an invented past onto the ruined present.

The process of reconstruction inscribes an invented past onto the ruined present.

With enough resources and effort we lift the ruin out of the fragmentary and set it down in wholeness, so that anyone encountering it no longer has to imagine it as it was but can see it as it could have been. But our attempts to reconstruct ruins against the ravages of sun and rain and wind and war and neglect are fraught from the start. What we end up seeing is always inaccurate, the product of research, plus creative fillings-in of the innumerable blanks. In the end, reconstruction becomes just another fiction, a fiction that people take as truth, since the fiction’s very concreteness, its completeness, its thereness, argue against its status as fiction.

There’s a sort of truth in the thing that falls down, falls into ruin, a truth about the natural cycle of things, which inevitably culminates in perishing. Against disintegration, maintenance is life. That’s how anything survives, by maintaining it. Ruin, the natural end to anything not properly maintained, ruin always marching toward complete disappearance. Therefore, you must maintain even a ruin, so that it doesn’t keep on ruining.

In our sometimes heroic, often foolish efforts to make whole the fragmentary, to maintain, we strive to cover over what the fragmentary is forever revealing: that most of the time we don’t really know what we’re looking at, and when we think we do, we’re relying on signs and assumptions that are almost certainly unreliable or speculative. That knowing what we’re seeing is a leap of faith we might not always want to make. That sometimes we should accept the unknown and the unknowable, to embrace what remains beyond our reach, to understand the ignorance imposed on all knowledge by the conditions of our living. That no matter how vigorous the maintenance, in the end we all come to ruin.

III.

We set off for the city and down we go, down to the fountain overlooking the pale, distant buildings, down to the steep stairs without railings, down the stony ramp and more stairs to little streets winding down the hillside, streets sided by close-pressing walls and shops. One shop in particular is walled with vintage instruments waiting to be repaired, and a cat guarding the door, asleep in the sunlight spilling over a cushioned chair. Something about those streets stirs something inside me—it never fails. Their pressing closeness, perhaps, which offers some primitive comfort. The worn stone underfoot. The quality of the sound, which seems so bound to the human, as if the sound had been absorbed into the stone or settled over it in a fine layer of dust, and the dust accumulated over days, years, centuries, so that those streets seem layered in all the sounds of their passing.

The light that filters down between the walls has a clear, generous feeling, a light that illuminates with a soft touch. And we walk through this light and between the layers of sound and over the stones in the street as among neighbors. As we go there’s a softening in our bones, as if we’re shedding some sharp, brittle flint, some calcifying that makes ivory of our insides, hard and cold. We soften like soap under a shower stream. We gel and bubble. We bend our arms now like dancers, whereas before we could only gesture woodenly, mimelike, pointing with jabs and pokes. And our legs bend, not just at the knees and ankles but at the thighs and calves. The bending no longer angular and creaking but fluent, flowing, like lava. The bending a kind of softness we didn’t know in ourselves.

Soon it comes over us like a wave, the bending. We bend at the ribs, we bend at the forearm, we bend at jaw and cheek. We bend at our temples and the loose folds of flesh behind our arms, those tender fingerholds just below our shoulders. Here we bend, thither we bend. The sound layered about our heels, the light cradling our bending, as if the crescent of the moon had descended from last night’s sky and sunk into the late afternoon, between those walls, filling that winding way with a crescent’s gentle light. Rocking us down, down to the river, where we arrive clad in our softness. Bent at every point, bent and soft, bending and winding down to the footbridge, which spans the river like a rope stretched between trees.

Into the city with its markets and squares. And all the old churches, each with the majesty of edifices meant for adoration and glory, their doors humbly open, their signs calling for quiet. We pass through the doors into the overdim vestibules, into the stone-lined hush of the sanctuaries, where signs of maintenance are everywhere—scaffolding and barriers and tarps. But the stones remain attuned to the larger forces; they endure maintenance patiently, exuding a reverence, not for the maligned suffering of gods worshipped under their watch, but for their own slow, dignified deterioration, having withstood storms and wars and progress. Progress halted at the door like a traveler bereft of the necessary papers.

It’s a great relief for once, a revelation, to walk on and leave progress behind.

It’s a great relief for once, a revelation, to walk on and leave progress behind, to walk into a stillness preserved for centuries, with a stale odor of shadowed stone, and a hovering sort of silence, a backward-reading expectation. As if spirits could be summoned with the proper incantation—somber, disapproving spirits, ruffled and lumbering, spirits woken from an ages-long sleep, the possibility of their waking arrayed through the hovering silence. The paintings posed along the walls seem to want to speak plainly from their perspectival flatness, the statues and tapestries waiting for us to look away and leave so they can continue their conversations in peace.

Now in this latter portion of our so-called adulthood, now that our frames are cracking, the cogs losing their teeth, now creaking as they turn, the dimness grows even more dim. Looking at the paintings and tapestries and statues is like seeing one’s ancestors through an unlit tunnel filling with fog. They seem to back away, but slowly, almost imperceptibly, as if the fog were closing over them like a lid, or as if they were falling to the bottom of a well, where the bucket rests on the water’s back like a thimble on an open palm. We wipe our glasses on the hems of our shirts. We rub our eyes and squint in concentration, but it’s no use; the fog closes in, like curtains drawn across a window. As if it’s all over—whatever era we had come to see—and we stumble for the door holding our hearts, as if to keep them inside our chests, and back out to daylight, the tourists feeling their way over the stones like the blind.

Decatur, Georgia