Historical Biographical Fiction

When I first read Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, I’d been working on a novel about Tudor-era martyr and writer Anne Askew for over a decade. My head buried in research, I’d been struggling toward a voice, a lens, a pathway into the story. Reading Mantel’s work broke that open for me. Historical biographical fiction can complexify and reshape our understanding of famous people, who they were on the inside, why they did as they did. For the writer, the plot is largely prescribed, because these things did happen to this person this way, but the why of the story, the voice, the form of the novel: these are all up for grabs.

In her essay “Why I Became a Historical Novelist,” Mantel wrote that she would make up a man’s inner torments but not the color of his drawing-room wallpaper, because someone somewhere might know the color and pattern, and if she kept searching she might learn it. I try to write to the ones who know the wallpaper. In researching the life of Anne Askew for my novel Prize for the Fire, I sought first the facts: how did people live in sixteenth-century England? What were the political, religious, social mores of the day? What happened in this young woman’s life to bring her to the fires of martyrdom? Then I listened for a voice to tell the story. That voice, over the course of many years, gave me the why.

Hilary Mantel’s masterful Thomas Cromwell trilogy showed me the capacious powers of historical biographical fiction. In honor of her life and work and influence, I’ve selected four books that plumb the lives of real historical persons. As a reader, I delight in the myriad forms this genre can take. These writers each chose a unique slant for their stories of real women who lived and breathed and walked the earth, each of whom, in her own time and place, made history.

Katherine J. Chen

Katherine J. Chen

Joan

Random House

AS SOON AS I saw the advance praise for Joan, Katherine J. Chen’s novel about Joan of Arc, I knew it would go on my to-read list. To embark on a novel about a woman of such fame requires courage and vision: how to reimagine a person whose story has been told so many times over the centuries in plays, poems, operas, films, novels, histories?

Chen achieves the task brilliantly. The historical Joan shares similarities with the woman whose life I’ve been researching and writing for twenty years. Both Joan of Arc and Anne Askew were religious zealots who were ultimately labeled heretics and burned at the stake—not just for their faith but for their actions as women who would not accede to the roles their worlds prescribed for them. Both lived in a deeply patriarchal, blanketly religious age. Chen’s Joan is not a saint driven by faith or by hallucinatory voices but rather by her passions for justice, mercy, revenge. She is a warrior, an empath, a visionary, a political and intellectual adept. Chen makes the distinction, in her revealing afterword, between the Joan of the novel and the historical Joan, noting the liberties she had to take with history to create this deeply personal Joan. The result is a powerfully feminist, secular retelling of Sant Joan, perfect for our areligious age.

Perhaps the strongest recommendation I can make is to say that, once I’d finished, I turned immediately to read Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses, by Régine Pernoud—not to compare but to set the transcribed voices of Joan and her contemporaries contrapuntally with the fully fleshed, fully realized Joan of Katherine Chen’s novel. Both remain alive in me long after the covers of the books are closed.

Luis Alberto Urrea

Luis Alberto Urrea

The Hummingbird’s Daughter

Back Bay Books

I WAS INTRODUCED to Luis Alberto Urrea’s work through his lucid and wrenching nonfiction book about a deadly desert border crossing in The Devil’s Highway. His tour de force historical novel The Hummingbird’s Daughter, about his distant relative Teresita Urrea, the Saint of Cábora, became my next favorite of his books. Like Joan and Anne, Teresita was a woman driven by faith into the dangerous nexus of politics and religion. Indeed, she’s been called “the Mexican Joan of Arc.”

Urrea describes in his author’s note how he researched and wrote the novel over the course of twenty years, immersing himself in Teresita’s era, culture, healing arts, faith, language—the full complex scope of her world. The result is a sweeping narrative that brings the reader fully into late-nineteenth-century Mexico, Catholicism and Indigenous belief, magic realism and historical fact. Teresita was a Yaqui mystic, a healer, a revolutionary who inspired uprisings against the ruthless Mexican president Porfirio. Like Joan, she began to experience religious visions after a serious illness in her youth. Like Anne, she offered public sermons about justice, equality, and brotherly love in an era when no woman was allowed to speak for the church. In Teresita’s time, as in Joan’s and Anne’s, a woman’s power derived from her religious faith—and the faith others placed in her.

Urrea makes this clear through his evocative depictions of era, religion, culture, and place. The Hummingbird’s Daughter is an immersive read, rich in language and period detail, and as a stylist, Urrea is unparalleled. He paints Teresita’s world and its vast cast of characters with humor, beauty, pathos, intricate historical knowledge, and a spiritual wisdom and compassion few writers can touch. This book exemplifies the exquisite tapestry historical biographical fiction can weave: a multilayered, multigenerational, multidimensional tale of a real flesh-and-blood woman, a saint, a curandera, a flawed, epic human at home in her elaborate, many-peopled world—a world Luis Alberto Urrea has plumbed at depth to bring us this gift.

Priya Parmar

Priya Parmar

Vanessa and Her Sister

Random House

FAR FROM saints, Vanessa Bell and her sister Virginia Woolf have long interested me because of their artistry, their sisterhood, and because they, too, were women who would not settle into the restricted roles their society prescribed for them. My love of Woolf’s writings first brought me to Priya Parmar’s Vanessa and Her Sister, but it is the beauty of Parmar’s language, her narrative choices, and the skillful portraits she paints of the sisters and their Bloomsbury cohorts that cause me to celebrate this novel and its subtle wonders.

Parmar channels the voice of Vanessa Stephen in an imagined diary (Vanessa wrote many letters but did not keep a diary as Virginia did), supplemented with created letters from others of the Bloomsbury group, along with telegrams, train tickets, and postcards as visual images, to create her narrative. The result is a compelling portrait of the sisters and their world in Bloomsbury that accumulates gracefully to a piercing and powerful ending. In her author’s note, Parmar acknowledges the challenge of fictionalizing lives that are so well documented. Finding her way meant, she says, “finding enough room in the negative spaces they left behind.” By sight and sound, insight and imagination, she fills those spaces splendidly. Her subtle, elegant prose renders persuasively the dramatic early years of the Stephen sisters and the soon-to-be famous Bloomsbury friends well before they became famous.

The turmoil beneath the surface, the jealousies and love affairs, ambitions and hungers, are all here. The events, as Parmar notes in her afterword, are accurately depicted, the internal landscapes of the characters completely imagined. This book is a quiet treasure.

LeAnne Howe

LeAnne Howe

Savage Conversations

Coffee House Press

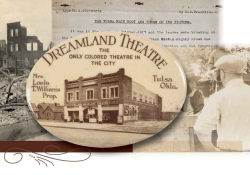

THE FIRST TIME I heard LeAnne Howe channeling the voice of Mary Todd Lincoln, I sat in stunned silence (as did the entire audience) when she finished: stunned and moved and amazed at the power, authenticity, and pain (see WLT, Sept. 2016, 50). This was one of the first public readings of what was to become Howe’s acclaimed book of dramatic verse, Savage Conversations. We were at a writing conference in Ada, Oklahoma, where LeAnne has an ancestral home, and I knew at first listen this was a radically important work.

Poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, scholar, Howe (Choctaw) is a writer of such magnitude and grace, it is no surprise she is the writer who put together the synergism of Mary Todd Lincoln’s tortured visions in an asylum years after her husband’s assassination and his signing off on the largest mass execution of Native prisoners in US history. Salted through with footnoted facts and archival phrases that give horrific bona fides to the story, Savage Conversations is like no other work of historical biographical fiction. A poetry-infused play, a work of dramatic verse, a short nontraditional novel, Savage Conversations is all these things: unique, unbound by settler narrative expectations.

Dakota writer Susan Power’s introduction gives an Indigenous and very personal context to the history underpinning Howe’s story: the mass hanging of thirty-eight members of the Dakota tribe in Mankato, Minnesota, on December 26, 1862, upon the orders of President Lincoln. In 1873 Mary Todd Lincoln was “put on trial” for insanity, testified against by her surviving son, Robert, and remanded to Bellevue Place Sanitarium in Batavia, Illinois. At Bellevue she suffered the recurring appearance of a “savage Indian” who would visit her nightly to scalp her, dig holes in her cheekbones, and, most tellingly, slit her eyelids with flint and sew them open with wire. Her husband had signed the death warrant to execute the Dakota men, and a decade later his wife was deemed insane, imprisoned, tortured, haunted. These are historical facts.

In Savage Conversations, the character Savage Indian is one of those hanged Dakota men. “Even with your eyes sewn open,” he says, “you still see nothing.” The haunting of Mary Todd Lincoln is like the haunting of the United States for the genocide and mass execution of Indigenous people. The ghosts may live among us, our eyes may be sewn open, but, still, we do not see.