Timbooktoo: The Pipeline Bookshop

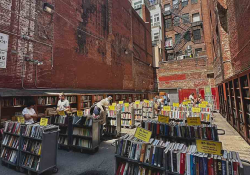

BOOKSTORES ARE OFTEN pegged as refuges, sanctuaries, havens, and the like, but they behave more accurately like consulates. With their filing systems, scuttling attendants, and all too increasingly common security cameras, they are the administrative conveyors of minds from one foreign locale to another, a pipeline of transition. Their shelves of rowed-up spines, like tourism brochures, are their promise of passage, of egressions into other worlds. The purchase is the receiving of a visa, and the release of the almond smell of old paper the sign a border has been crossed, and a country of like minds entered. It’s little wonder that Faulkner is as transportive in West Africa as Soyinka is in Mississippi.

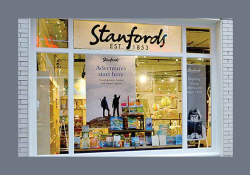

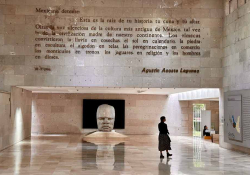

With its cool blue and chalk-white edifice, the Gambia’s Timbooktoo Bookshop has all the remove of the American consulate on nearby Kairaba Avenue, without any of the latter’s aggressive iron fencing or the speciously green lawn. No wonder, then, that while sitting on Timbooktoo’s second-story terrace, drinking an espresso, and looking down over the taupe dust of Garba Jahumpa Road, which rises in thick, tight clouds behind each passing car, I finally felt the relief of arrival.

Timbooktoo has occupied this place, as grand and imposing as the prow of Moby Dick’s great skull, since 2005, when owners Katie Paine and her husband, Ousainou Jagne ,moved it from its original location on Pipeline Avenue (hence its epithet, “The Pipeline Bookshop”). As the Gambia’s sole bookstore, it remains the conduit not only for the nation’s literary circles but a font of inspiration for its nascent readers and writers.

Now in the drowsy suburb of Fajara, some eight miles west of the nation’s capital, Banjul, it’s forgivable to think that Timbooktoo might exist for the plethora of European tourists who ordinarily bung up nearby Kololi beach. But it isn’t so. Customers are largely those living locally, whether Gambian or expatriate, of which there is a sizable permanent community. “Tourists,” Paine says, “are the froth on the coffee. They buy a map and a drink, or a book about West Africa. Or maybe a Grisham, or a Sidney Sheldon for the beach.” Rather, the majority of business comes from school books—textbooks, notebooks, and lesson manuals—that are ordered by schools throughout the Gambia. Paine points out they also send books to outlying schools who can’t afford them or wouldn’t otherwise be able to receive them. “We’re not just here to run a business,” she says.

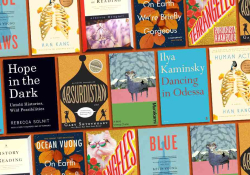

Of running the business as a couple, Paine says, “We complement each other. I can predict the needs of our foreign clientele, while Ous knows what our local shoppers want.” Perhaps nowhere is this on better display than with the bookshop’s Mr. and Mrs. tables. Mr. Table, curated by Jagne, proffers up such titles as The Power of Positive Thinking, The Meritocracy Trap, and Nesrine Malik’s We Need New Stories. Across the aisle, Mrs. Table offers, among others, The Old Drift, by Namwali Serpell, and Wayétu Moore’s She Would Be King.

Banjul’s fiction readers are few enough that Paine reckons she “can name them all.” She estimates that, of the books Gambian adults buy for themselves, only ten percent are fiction. The other ninety percent, she says buy “mainly for their children, and concentrate on self-improvement, or perhaps African politics or history.” Though fiction doesn’t move quickly, each month a selection of both fiction and nonfiction arrives from England to complement their collection of local Gambian writers. “We’ve been doing well with Bernardine Evaristo. And Chimamanda always sells well. And Yaa Gyasi has been popular lately.” Barack Obama’s A Promised Land is their most recent best-seller. Timbooktoo also hosts a weekly book club (Atwood’s The Testaments was February’s choice, with Paine tutting its “rather tidy ending.”).

Those buying for children are particularly spoiled for choice, with half the store given over to children’s literature. Among them are Miranda Paul’s One Plastic Bag, a true story about a local Gambian woman’s attempt to rid her country of its plague-like levels of plastic, and Lupita Nyong’o’s Sulwe, whose message on skin tone provides a heartening contrast to the billboards advertising “skin-lightening” creams lining Gambia’s thoroughfares.

There is, too, a sizeable selection of local books, by and large produced in the printing houses found in the backstreets of the Greater Banjul Area, which publish books for “human advancement” alongside selling photocopies, stationery, and scientific equipment.

Though promotion of local writers is one of Timbooktoo’s tenets, Paine admits that reading isn’t a priority for most Gambians, the majority of whom routinely face the challenge of making their daily bread. Books range in price from 150 dalasi for second-hand to 500 new (approx. 50 dalasi per USD), which is cost-prohibitive for many. And though English is the lingua franca of both the streets and halls of Gambian government, Mandinka, Pulaar, and Wolof are the core languages of the country. While these indigenous tongues are rich with mythology, stories, and present-day accounts of modern Gambian life, they remain at heart oral languages. For now, slim volumes by unknown writers are found alongside the nation’s literati: Lenrie Peters, Hassoum Ceesay, Tijan M. Sallah, Dawda K Jawara, and Nana Groy-Johnson.

The hope that more Gambians will take up the pen is there. Timbooktoo’s logo, looking like one pair of downcast eyes above another, is a West African Adinkra symbol, the Ntesie. As a symbol of wisdom and knowledge, it characterizes the aphorism “What I hear, I keep.” And so, the stories are there, waiting to be recorded. Like any good literary embassy, Timbooktoo will dutifully allow access.