Editor’s Note

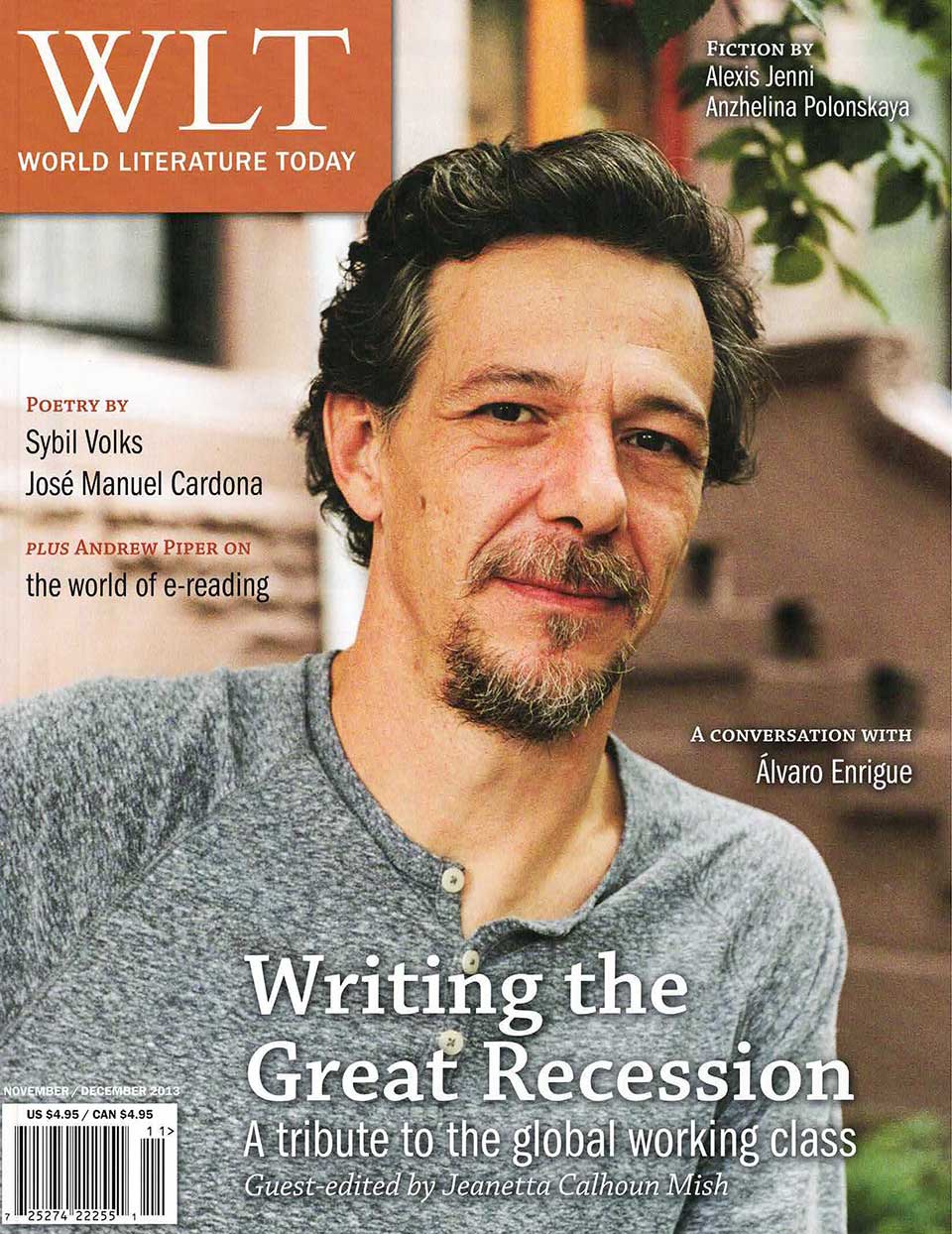

Five years on from the Great Recession, WLT is proud to present an international sampling of working-class literature, guest-edited by Jeanetta Calhoun Mish (page 34). We hope readers will enjoy the diverse range of voices presented in these pages. Yet as I write this note on Labor Day 2013, I’m struck by how indolent writing can be. With my laptop, I can sit at the kitchen table or in a café amid comfortable surroundings, delecting language and savoring the leisure of writing. Leisure, as in “the opportunity afforded by freedom from occupations,” the OED tells me. Of course, writing is itself an occupation, but often a suspect one in the eyes, say, of my family, who wander into the kitchen wanting something to eat. And since writing by itself doesn’t put food on the table, I must set it aside and devote the labor of my hands to the “real,” practical work of supporting—feeding, raising, nurturing—my family.

Five years on from the Great Recession, WLT is proud to present an international sampling of working-class literature, guest-edited by Jeanetta Calhoun Mish (page 34). We hope readers will enjoy the diverse range of voices presented in these pages. Yet as I write this note on Labor Day 2013, I’m struck by how indolent writing can be. With my laptop, I can sit at the kitchen table or in a café amid comfortable surroundings, delecting language and savoring the leisure of writing. Leisure, as in “the opportunity afforded by freedom from occupations,” the OED tells me. Of course, writing is itself an occupation, but often a suspect one in the eyes, say, of my family, who wander into the kitchen wanting something to eat. And since writing by itself doesn’t put food on the table, I must set it aside and devote the labor of my hands to the “real,” practical work of supporting—feeding, raising, nurturing—my family.

Just as traditional labor roles have evolved in my lifetime, notions of acceptable work continue to modulate. I grew up on a farm, and although my parents’ mantra—“You can be a ditch digger, as long as you’re the best ditch digger you can be”—made it seem like we could do just about anything, the leap from “acceptable” to “respectable” work was a categorical one. I was the third of five boys, the “bookish” one—my aunt and uncle called me “little professor”—often chided for having my nose in a book when there were chores to do. When I followed my older brothers’ footsteps to the University of Nebraska in 1985, I dutifully declared a major in aeronautical engineering until the siren song of a Shakespeare class lured me into an academic career centered on words. I know that publishing, writing, and teaching count as respectable careers, but is it work, really?

My maternal grandfather, Leo G. Simecka (1908 –2001), worked as a boilermaker for thirty years, repairing locomotives for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe shop in Topeka, Kansas. While he was a card-carrying member of Local 34 of the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, he never went on strike, and I suspect that he never had a strong sense of class consciousness or solidarity with an international brotherhood beyond his coworkers in the shop. “Class is as much a cultural as an economic formulation,” labor historian E. P. Thompson famously wrote, and “it was in the communities, the churches, the oratory, and the propinquity of place that workers expressed their solidarity” (Jefferson Cowie, “Working Class,” 2001). Although my grandfather could tell you exactly how much he made at various times in his life—ten cents an hour cutting wood on the farm in his youth, three dollars a day teaching grades 1–8 in a one-room school in the 1930s, and forty-nine cents an hour when he started working nights for Santa Fe in 1942—most people knew him more as a gardener, fisherman, and farmer than as a blue-collar laborer. The entries in the daily journal he kept for most of his life dealt mostly with the weather, the produce he sold out of his garden, or the number of fish he caught every year (636 in 1976). One of his lasting legacies is that he helped put fourteen grandchildren through college, which for all of us was a promise of a better life.

One of my cherished books is his copy of A. B. De Mille’s American Poetry anthology (1923), which he must have studied while he was a senior in high school—numerous poems have their rhyme schemes and meters marked. Among the poems my grandfather noted as his favorites are Longfellow’s “The Village Blacksmith,” whose fortunes are wrought “at the flaming forge of life,” and Edwin Markham’s “The Man with the Hoe,” in which, on behalf of the toiling field-worker, the poet “Cries protest to the Judges of the World, / A protest that is also prophecy.”

Prophecy has its place, but there’s work to be done in the meantime. I can just hear my grandfather say, “Get goin’, Danny Boy.”