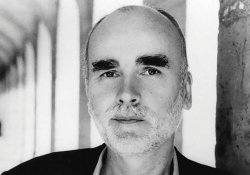

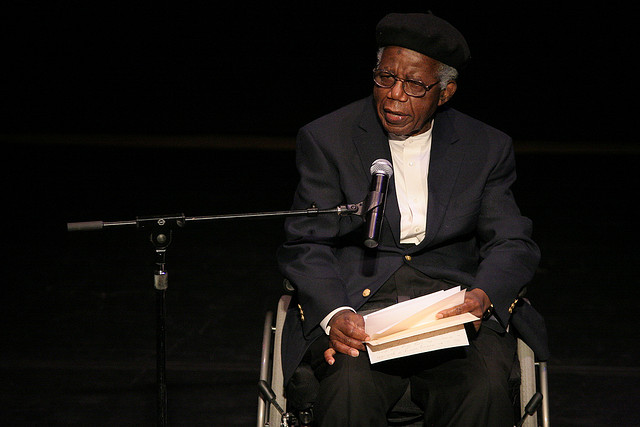

Chinua Achebe: “One of the great intellectual and ethical figures of our time”

In tribute to Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who passed away this Thursday at the age of 82, we’ve opened the vault to share these compelling and inspiring words by Gabriel Okara in his nominating statement for Chinua Achebe for the 2004 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. Achebe was a candidate for the Neustadt Prize in 1994 and 2004, and was a member of the Neustadt jury in 1974. His most recent book, There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra, is reviewed in the current issue of WLT and available to read on the WLT website.

Neustadt Prize Nominating Statement for Chinua Achebe

by Gabriel Okara

Chinua Achebe is unquestionably one of the outstanding and best-known writers to have emerged from colonial and independent Africa. He is a social critic and political activist of an egalitarian bent. As a writer, he has many novels and nonfiction works to his credit, the most famous of which is Things Fall Apart. This I have taken as the representative text of his work. It is widely acclaimed in Africa, Europe, and the Americas as his masterpiece. He is a staunch advocate, among others, of an African using his former colonial master’s language as his means of expression, to use it in such a manner as to give his creative writing an authentic African stamp. This he has done successfully in the novel Things Fall Apart. Herein lies its universal acclaim: the telling impact it has had on world literature.

Things Fall Apart is an eloquent indictment and exposé of the white man’s ignorance of the African and the culture of the continent and a condemnation of Western materialism. With his missionary posture, the white man cut loose the cultural roots of the African and other white racial groups in North and South America, the West Indian islands, and elsewhere. The Ethnic nationalities, the aborigines of these countries and Islands, were sent adrift in the shallows and deep currents of cultural anonymity, confusion, and instability. As a result, things indeed fell apart. None of the peoples of these countries successfully resisted the onslaught of the purported European mission of civilizing the uncivilized and of bringing light to the Dark Continent by influence and exploration.

Okonkwo, with his rugged and adamant nature, is the hero of Things Fall Apart. The plot of this seemingly simple story is woven through and around this inflexible, rocklike traditionalist. He is, indeed, the embodiment of the universal spirit of resistance to the subtle tearing apart of the fabric of traditional societies by the white man; first with religion, followed by the imposition of his system of government, and then by the undistinguished economic exploration of the land and its people for the enrichment of his country. If persuasion with religion failed to achieve this, then the sword, hidden in the cloak of religion, is unsheathed. The people yield but not without some spirited engagement. Indeed, it took years of fighting in some parts of the world before resistance was finally quelled, but the aftermath was the same: cultural chaos, alienation, and near total breakdown of traditional values and practices. The Red Indians put up a valiant fight for the sanctity of their tradition and their land, which “Pale face” was taking away from them by force of arms. The Indians, of course, were defeated. These once free-roaming people on their horses in the wide prairies are now huddled in reservations like an endangered species of humans. The Indians of Mexico and other Latin American countries, the Caribs of the Caribbean Islands, the Maori of New Zealand, and the Aborigines of Australia suffered the same fate to various degrees.

The dénouement of the story in Africa is somewhat different. Indeed, white people did settle and made their homes in the eastern and southern parts of the continent. However, they were forced to relinquish power to the Africans as a result of the militant uprisings for independence that spread across the continent in the course of the twentieth century. Though Africans had gained independence, things were no longer the same. There had been too much change for things to remain the same for the African. Things had indeed fallen too much apart for the center to hold any longer, and anarchy was loosed throughout Africa. How prophetic Achebe was with the title of his book when you turn a critical eye on Africa today. They, the Europeans, left a flea on the dog of internal politics in their former colonial territories. (An English proverb says that if you want a dog to stop barking at you, leave a flea on its back).

Achebe, with his clinical and effective use of English (a colonial heritage), leaves no one in doubt of the Africanness of the delivery of his message. Its unambiguous clarity is enhanced by the prudent use of Ibo proverbs, which magnify the ambiance and the characteristics of the milieu in which this sad and tragic drama was enacted. Early in the novel, Achebe says of the Ibo: “Among the Ibo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten.” The reader is not left disappointed as he or she explores the twist and turns of Ibo traditions, beliefs, and practices with the Ibo master conversationalist and storyteller. This feature makes him stand out as unique among his African contemporaries. Thus the popularity of Things Fall Apart in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. I quote from the comments from the back cover of the Anchor edition of the novel, which has been sent to you, my fellow jurors:

More than two million copies of Things Fall Apart have been sold in the United States since it was published in 1959. Worldwide, there are eight million copies in print in fifty different languages. This is Chinua Achebe’s masterpiece and it is often compared to the great Greek tragedies, and currently sells more than one hundred thousand copies a year in the United States.

And in England, he is cited in the London Sunday Times as one of the “1000 Makers of the Twentieth Century” for defining “a modern African literature that was truly African and thereby making a major contribution to world literature.” His volume of poetry Christmas in Biafra, written during the Biafra War, was the joint winner of the first Commonwealth Poetry Prize. Among his novels, Arrow of God won the New Statesman–Jock Campbell Award, and Anthills of the Savannah was a finalist for the 1987 Booker Prize in England.

Mr. Achebe has received recognition and acclaim from around the world, including an honorary fellowship from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, as well as more than twenty honorary decorates from universities in England, Scotland, the United States, Canada, and Nigeria. He is also the recipient of Nigeria’s highest award for intellectual achievement, the Nigerian National Merit Award.

And finally, I again quote from the back cover of the Anchor edition of Things Fall Apart. Leon Botstein, president of Bard College (where Achebe now teaches), has this to say: “Chinua Achebe is one of the great intellectual and ethical figures of our time.” Given all the above, I am sure Chinua Achebe has met the very high standards of excellence set for the Neustadt International Prize for the Literature.

Fall 2003

Port Harcourt, Nigeria

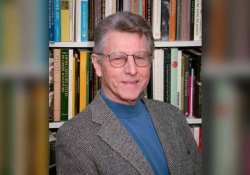

Gabriel Okara is a Nigerian poet and writer born in Bomoundi in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. He won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize in 1979 and established the River State Government Paper, The Nigerian Tide. His published books include The Voice (1970) and The Fisherman’s Invocation (1978). In addition to his poetry and fiction, Okara has also written plays and features for broadcasting.