China’s Minority Fiction

China’s fifty-five officially recognized “minority peoples” make up less than 9 percent of the People’s Republic of China. Still, they number more than 130 million, and their literature deserves study both for its political urgency and for its lyricism and philosophical power. Multiethnic fiction speaks volumes about Chinese attitudes toward minorities, as well as these peoples’ historical understandings, their search for roots, and longings for cultural survival.

What Holds China Together?

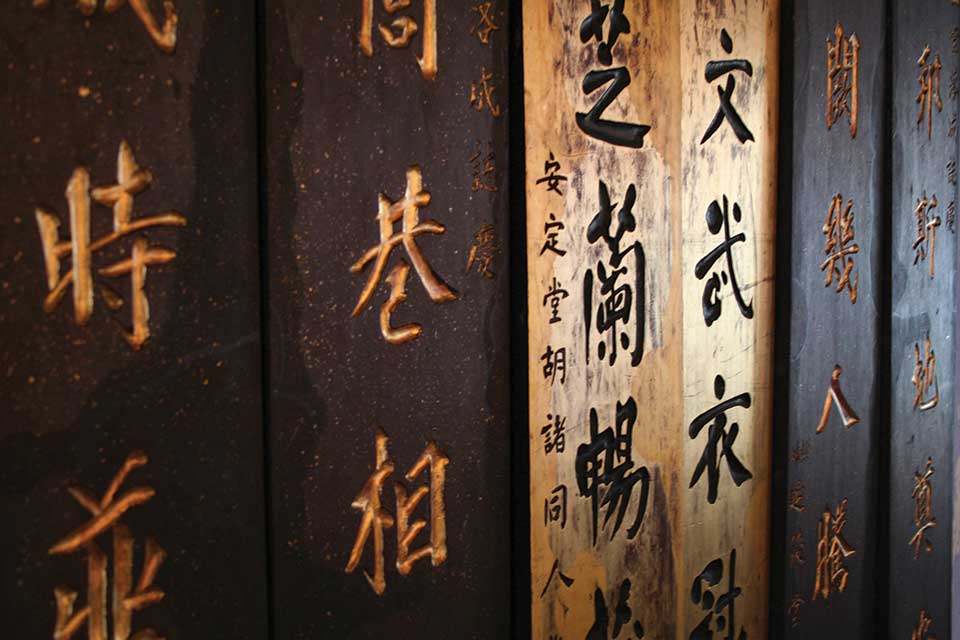

How has literature enabled China’s evolving empire? Rather than a continuous polity, “China” names a culture. It may be this culture’s seemingly infinite resilience that confers political legitimacy. What has made Chinese culture so resilient? For three thousand years a powerful literary tradition has held together diverse and sometimes competing civilizations.

The written language has been the glue that connects Chinese people to a shared cultural past. Throughout the region’s history, what counts as “Chinese” has been shifting. Yet even as Chinese characters, literally “Han words” (漢字), have evolved over time, expert sinologists can still read the inscriptions on tortoise shells and sheep scapulae from the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 bce). Identification as a people has hinged on this written language.

Written Chinese has also enabled communication across disparate spoken dialects, including those of ethnic minorities. For ethnic groups with their own languages, from the Mongols and Manchus that once conquered and ruled the realm to contemporary Tibetans and Uyghurs, writing in Chinese has brought status and acceptance. The cost has been Sinification, a homogenizing trade-off.

Literary writing has also been fundamental to governance, likely more so in China than anywhere else. To enter the civil service, scholars had to master the core philosophical canon and poetic composition. Thanks to a long tradition of scholar-officials who remonstrated with rulers, such texts also served as voices of conscience. The Chinese Communist Party continues to recognize the political power of writing, and literature in particular, through the PRC’s official organ for writers, the Chinese Writers Association (CWA).

Who Counts as Chinese?

During the Civil War of 1946 to 1949, the Chinese Communist government adopted the Soviet paradigm using the term “nationalities” (民族) to refer to ethnic groups within the empire. Ethnic Han Chinese had earlier conceived of themselves in terms of a center-periphery model. This new notion of “nationalities” made the empire’s internal nations, cultures, and ethnicities distinct categories of official discourse. These distinctions paved the way for the establishment of the “autonomous regions” of Inner Mongolia (1947), Xinjiang (1955), Guangxi (1958), Ningxia (1958), and Tibet (1965).

China’s label of “autonomous” for these areas should not be taken at face value. They are always subject to Beijing’s dominion; their powers of self-rule are even less than the modest rights begrudged to Indigenous peoples on US reservations or among Canada’s First Nations. In China, these cultures’ distinctiveness has meant that their inclusion within the PRC has entailed battles over independence and identity that some have called civil wars.

The autonomous regions’ powers of self-rule are even less than the modest rights begrudged to Indigenous peoples on US reservations or among Canada’s First Nations.

China’s fifty-five officially recognized “minority peoples” (少数民族) make up less than 9 percent of the PRC. Still, they number more than 130 million, and their sparsely populated homelands account for over 45 percent of the country’s area. On the Chinese Writers’ Association roster of 12,000-plus members, more than 1,500 are self-identified ethnic minorities. Many of these non-Han writers represent their group’s first generation of published authors. Since 1976, Chinese presses have issued hundreds of novels by minority writers on ethnic themes. In addition, at least eighty literary magazines (about half in ethnic languages) publish poems, stories, and essays by minority writers. These ethnic groups all have long oral traditions, and their cultures are distinct enough to make China a multinational polity, more analogous to the European Union than to a single country.

Fiction and Survival

Dynamic and defiant, fiction by China’s ethnic minorities offers clarion voices amid the din of Chinese nationalism and party discourse. Often lyrical and nostalgic, this fiction documents the pluralism of cultures within China’s historically shifting borders. In so doing, multiethnic fiction undercuts myths of a unified “Chinese” culture. It also speaks volumes about Chinese attitudes toward minorities, as well as these peoples’ historical understandings, their search for roots, and longings for cultural survival.

Should non-Han writers be considered Chinese writers? Referring to them as “minority Chinese” would be akin to calling writers both from and in former French colonies such as Algeria, Guadeloupe, and even Vietnam “minority French writers.” Maryse Condé, from Guadeloupe? Maybe, but usually “francophone.” Tahar Ben Jelloun, from Morocco? Maybe not. Yet the Chinese Writers Association not only promotes but also appropriates ethnic authors both within and beyond their Indigenous homelands.

Documenting Suppressed History

Many historical novels by ethnic writers document suppressed history, recover endangered traditions, and bespeak the pathos of cultural assimilation. Lao She 老舍 though most renowned for his works on the downtrodden in Beijing, paints a nostalgic portrait of his Manchu upbringing in his unfinished autobiographical novel Beneath the Red Banner《正红旗下》(1961–62). Despite his family’s reduced circumstances, Lao She presents a burnished vision of late-Qing Manchu customs. The novel’s idealization of pre-revolutionary life deferred its publication until 1979, thirteen years after Lao She’s suicide during the Cultural Revolution.

Many historical novels by ethnic writers document suppressed history, recover endangered traditions, and bespeak the pathos of cultural assimilation.

Some writers such as Tibetan author Yeshi Tenzin 益希单增 focus on periods before the 1949 revolution. In recounting 1930s and ’40s Tibet, Yeshi’s The Defiant Ones《幸存的人》(1981) depicts bitter class antagonisms and the hypocrisy rife in Buddhist institutions. Whereas the author may have proffered it as an apologia after his political persecution, the novel nonetheless conveys sympathy for regional values and folk traditions. At the same time, these rustic vignettes hardly soften the novel’s critique of feudal Tibetan practices.

Resistance to foreigners, and especially the Japanese invasion, is a common theme, as in the Manchurian writer Zhu Chunyu’s 朱春雨 melodramatic trilogy, Bloody Bodhi《血菩提》(1989). Zhu’s novel depicts a patriotic bandit’s life in Manchuria after the Mukden Incident of 1931 and Japan’s ensuing colonization. Mongol writer Li Zhun’s 李凖 Yellow River Flows East《黄河东流去》(1979–85, winner of the Mao Dun Literary Prize) tells of the resilience of rural peasant refugees during the harrowing Japanese invasion of 1938 to 1945. Hui writer Huo Da 霍达 chronicles the British subjugation of Hong Kong in her elegiac Patching a Broken Sky《补天裂》(1997).

Similarly focused on collective memory, historical fiction on post-1949 history is less common and more controversial. Undaunted, Tibetologist Jambian Gyamco 降边嘉措 devoted twenty years to writing his novel Galsang Meido《格桑梅朵》(1980). The flower of good fortune of the title symbolizes the love between a young couple, recruits in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The work offers a partisan account of the PLA troops’ heroic fording of the Jinsha River and subsequent occupation of Lhasa in October 1950.

Whereas such works testify to optimism and shared purpose, works by Tibetan and Uyghur nationalists often express a longing for self-determination. Some even issue subtle calls for a return to independence. The Uyghur homeland in Xinjiang has been in and out of China’s control since 60 bce. The area now named Xinjiang (新疆), or “New Frontier,” was for centuries called the “Western Region” (西域) and later “East Turkestan” (东突厥斯坦), a sporadically independent country from 1931 until its annexation by the PRC in 1949. At its peak in the eighth century, the Tibetan empire encompassed much of what is now western China, northern India, and central Asia as far as eastern Kazakhstan. Today both Xinjiang and Tibet may effectively be colonies.

Not surprisingly, Chinese translations of Uyghur works often echo but tone down these works’ resistance to Chinese domination. Such editorial control spins the book titles of Uyghur writer Abdurehim Ötkür 阿不都热依木 ·乌铁库尔 (1923–1995). Best known as a poet, Ötkür was imprisoned from 1949 until the late 1970s. Nonetheless, he fearlessly describes Uyghur nationalist resistance during the Hami rebellion (1931–34) in Traces《足迹》(1985), The Awakening Land, Part I《苏醒了的大地》, 第一部 (1988), and The Awakening Land, Part II《苏醒了的大地》, 第二部 (1994).

Ötkür’s novels have thus been interpreted as not only testimonies of respect for Uyghur cultural heroes, heritage, and values but as veiled support of Uyghur nationhood. The first word in the original Uyghur title means “that was awakening,” an oblique allusion to burgeoning Uyghur nationalism in the 1980s. To evade censorship, however, the title had to be rendered in the past perfect tense when translated into Chinese, The Awakened Land. The softer “awakened” could imply that Uyghur awakening in the 1920s and ’30s had been part of a general Chinese awakening addressed once and for all by the Liberation in 1949.

Search for Roots

In the mid-1980s, almost a decade after the ravages of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, many minority writers, like their Han counterparts, probed traditional customs in what came to be known as “search-for-roots” (寻根文学) literature. The movement was inspired by Alex Haley’s best-selling 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family and the blockbuster television miniseries it spawned. (The Chinese translation of the book appeared in 1979.)

Hui author Zhang Chengzhi 张承志, for example, gained prominence with Rivers of the North《北方的河》(1984) and other works on the Hui of northwestern China. He combines fictional memoir with poetry and history in his best-selling historical narrative History of the Soul《心灵史》(1991). Zhang integrates his own conversion to Islam with the 172-year history of the Jahriyya Sufi. Even as he recounts their movement’s suppression at the hands of Qing armies, the novel continues the lyricism of Zhang’s earlier works. Full of empathy for peasants and herdsmen, the novel searches for both the narrator’s and the nation’s soul.

While some writers showcase their cultures as exotic elements of Chinese culture, more portray their traditions in quiet protest against Han domination and the country’s turn toward materialism.

Like Zhang—who evolved from an ardent Red Guard, to roots-seeking writer, to critic of rising Chinese materialism—many minority writers are multifaceted. While some writers showcase their cultures as exotic elements of Chinese culture, more portray their traditions in quiet protest against Han domination and the country’s turn toward materialism. Political tensions figure powerfully, though at times obliquely. Caught between spiritual and secular concerns, and between traditional and modern values, many characters voice longings for autonomy. But most also struggle with the compromises and disappointments of assimilation.

In representing the period of market transition, much fiction evinces a shrewd take on urban development, as in Tujia writer Sun Jianzhong’s 孙健忠 rags-to-riches novel Drunken Village《醉乡》(1986). Yao writer Lan Huaichang’s 蓝怀昌 Bonu River《波努河》(1987) similarly narrates a young Yao woman’s rise and demise as an entrepreneur. Winner of the Mao Dun Literary Prize, Huo Da’s 霍达 Muslim Funeral《穆斯林的葬礼》(1988) chronicles three generations of Hui jade carvers in Beijing. The novel exalts hard work and upward economic mobility as a rebuke to Han stigmatization of the Hui, but it also testifies to the wages of jealousy and false identity.

As minority writers navigate hybrid identities and cosmopolitan influences, magic realism often serves to highlight existential dramas that transcend local politics and economics. The half-Tibetan Tashi Dawa 扎西达娃, writing in the Mandarin Chinese of his upbringing, crafts realist and magical-realist stories drawing on Tibetan storytelling traditions. From the conundrums of time in his short story “Tibet: Souls Knotted on a Leather Cord”《西藏,系在皮绳结上的魂》(1985) to conflicts between progressive pragmatists and spiritual traditionalists in his masterpiece Turbulent Shambala《骚动的香巴拉》(1993), Tashi Dawa strips away illusions of timelessness to confront the forces of modernization.

Longings for Cultural Survival

Beneath the search for roots lie deep longings for cultural survival. These interwoven themes dominate recent anthologies in English such as Tales of Tibet: Sky Burials, Prayer Wheels, and Wind Horses (2001) and Old Demons, New Deities: Twenty-One Short Stories from Tibet (2017). Whether written in Tibetan, Chinese, or English, these stories recount Tibetan Buddhist beliefs and practices, at times with critical overtones. The 2017 volume includes stories from the poet Woeser 唯色, filmmaker Pema Tseden 万玛才旦, activist blogger Tenzin Dorjee 丹增多吉, and Tsering Döndrup 次仁頓珠, author of The Handsome Monk and Other Stories (2019).

For Uyghurs and Tibetans, the heartbreak of oppression and exile is often projected onto elements of the natural world. The pastoral environment figures especially prominently in works by groundbreaking women writers. Yangdon 央珍 (1963–2017) , considered the first Tibetan woman novelist, observes both the majesty of nature and the refinements and afflictions of Tibetan culture in her masterwork, A God Without Gender《无性别的神》(1994).

Born in Tibet but educated in Nanjing and Beijing, Geyang 格央 (b. 1972)—who writes in Chinese—combines Buddhist influences with Chinese new realism. In the cinematic tale “An Old Nun Tells Her Story”《一个老尼的自述》(1999), the narrator’s reverence for nature instantiates her Buddhist wisdom. After her prosperous family sends her to a monastery at age eight, the young Buddhist nun bravely redresses a friend’s rape. She is then called home for an arranged marriage, ultimately falls in love with her husband of ten years, and later returns as a widow to the convent to share stories with the fellow nuns of her youth.

One of the most celebrated minority writers in China is Alai 阿来, a half-Hui and half-Gyarong poet from the Tibetan-majority area of Sichuan. (The PRC recognized the Gyarong as an independent ethnicity until reclassifying them as Tibetans in 1954.) Schooled in Chinese, Alai won the Mao Dun Literary Prize with his lyrical debut novel As the Dust Settles《尘埃落定》(1998; Eng. Red Poppies, 2002). Here Alai’s canny “idiot” narrator-protagonist chronicles the waning of the feudal chieftain system. As the market for opium turns poppies into a commodity monoculture, the subsistence grain economy crumbles. Because the narrator stubbornly continues the tradition of growing grain, when famine arrives his prescience consolidates his family’s power.

In his best-selling The Song of King Gesar《格萨尔王》(2009), a rewriting of the traditional epic ballad, Alai tells the parallel legends of King Gesar and Jigme, a herdsman who becomes a roaming bard and sings the epic. After Gesar visits him in a dream, lodging an arrow and a mission in his heart, Jigme devotes himself to tracing the king’s journey. Yet the humble storyteller comes to doubt the king’s glory, just as the king himself comprehends the persistence of greed, suspicion, and inequity. Alai subtly aligns Jigme’s position with that of traditional China. When Gesar ultimately removes the arrow from Jigme’s heart, the survival of both the epic and the storyteller appear to be at risk.

The question of cultural survival haunts Patigül’s Bloodline《百年血脉》(2015). The novel situates the narrator—who, like the author, is half-Uyghur and half-Hui—within the matrix of the Han majority’s aggressive promotion of Chinese:

As my father, he needed to demonstrate that he knew about Chinese, but . . . his knowledge was [just] bits and pieces he’d picked up from other Uyghurs in the village, and he still spoke Uyghur most of the time; I, on the other hand, went to a Chinese school and was setting sail into a Chinese-language world. (trans. Natascha Bruce)

The novel opens in Qochek, in the Kazakh autonomous prefecture of Xinjiang. Yet the protagonist soon leaves the city after a call from a voice claiming to be her older brother. Not sure it’s her brother, whose voice she hasn’t heard in five years, she nonetheless gives up her life in Xinjiang to go to Guangzhou. In this raw, wrenching, and at times brutal narrative, the protagonist’s search for her family members and their history encapsulates different possible futures for Uyghurs, especially assimilation, whether in Xinjiang or elsewhere in China.

Minority fiction reveals long-buried wells of nostalgia, resentment, strength, and hope. Celebrated for adding multicultural threads to the Chinese fabric of prosperity, these stories and novels often belie the façade of unity and inclusivity of the so-called minority peoples. With so few works available in English, both their quality and undeniable political urgency argue for more translations. This fiction deserves a wide readership, not only throughout the Chinese empire and its vast western regions, but globally.

Smith College