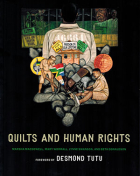

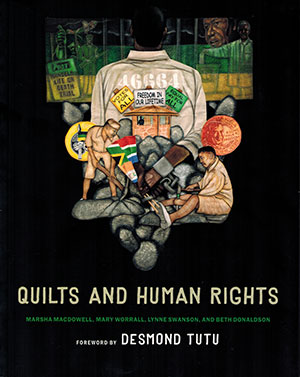

Quilts and Human Rights by Marsha MacDowell, Mary Worrall, Lynne Swanson & Beth Donaldson

Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press. 2016. 210 pages.

Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press. 2016. 210 pages.

In this lushly illustrated exhibition catalog, Michigan State University Museum curators Marsha MacDowell, Mary Worrall, Lynne Swanson, and collections assistant Beth Donaldson piece together a history of human rights–related quilt making, quilters’ narratives, and analysis of contemporary textiles. The authors survey quilting history in Europe and the United States, noting textiles made in support of abolition, temperance, women’s suffrage, and civil rights alongside more recent quilts responding to incarceration and violence. Particularly poignant are quilts stitched by indigenous hands that adopted the textile techniques of their subjugators to comment on their own loss of rights, including the gut-wrenchingly beautiful (but too briefly discussed) Queen Lili’uokalani’s Quilt, made by the Hawaiian monarch during her imprisonment in 1895. Although the authors claim to offer a global history, the text primarily concerns late-twentieth-century and contemporary American quilts. South African textiles form a second area of emphasis.

Engagingly written extended captions accompany each image, typically addressing the quilter’s process or the work’s (often disturbing) subject matter. Yet the real significance of this book—its most powerful expression and most potent communication—lies not in words but in its images. Some featured textiles resemble petitions signed in thread, recording the names of women whose lives and social concerns may otherwise be forgotten. Others—like the Boston Marathon and Oklahoma City Memorial Quilts—commemorate collaborative efforts toward community healing following acts of terrorism. Still other sophisticated designs represent the work of skilled artists. A thin young woman bends over her sewing machine in Therese Agnew’s striking Portrait of a Textile Worker, a monochromatic portrait composed of thirty thousand clothing labels. This eloquent image, meant to raise awareness for anonymous sweatshop workers, speaks no less powerfully than the trash, tarps, and cardboard appliquéd together in Jo Van Patten’s abstract mixed-media collage, The Fabrics of Homelessness.

In contrast to the powerful images, the essay unravels near its close into a list of quilt projects and exhibitions, material that might more usefully occupy an appendix. Readers may long for an art historical interpretation of each textile, if not a deeper discussion of their meaning. Ultimately, Quilts and Human Rights leaves the reader wanting more: more scholarship on these affecting works; more awareness for the critical issues they address; and, most of all, more tolerance, more understanding, and more value for human life in our world today.

Hadley Jerman

University of Oklahoma

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list

More Reviews

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Eva Sleeps by Francesca Melandri

Francesca Melandri. Trans. Katherine Gregor -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Umami by Laia Jufresa

Laia Jufresa. Trans. Sophie Hughes -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-