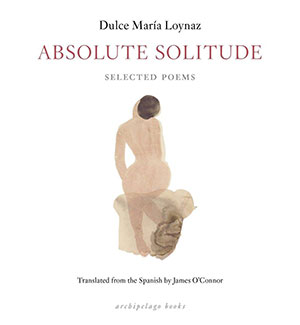

Absolute Solitude by Dulce María Loynaz

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2016. 263 pages.

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2016. 263 pages.

Raised in a progressive, prosperous Cuban family, Dulce María Loynaz (1902–97) gained a reputation for innovative writing. But after refusing to join the Communist Party, even as she remained in Cuba, her books were removed from libraries, and she became invisible. Later, in the 1990s, her work was rediscovered, and she was awarded the Cervantes Prize in 1992. Absolute Solitude includes prose poems published in 1953 as well as Melancolia de otoño, published posthumously in 1997.

Characterized by a restless fusion of European and Afro-Caribbean influences, Loynaz’s poems evoke the problematic dynamic of self, identity, and a deliberate dissolution. “Es la hora en que me borro a mí misma, en que yo me sujeto al corazón y me vuelvo a espaldas a tu tiempo” (This is the hour in which I erase myself, in which I bind my heart, and I turn my back to [or in accordance with] your time) (lx).

Chiaroscuro juxtapositions occur throughout her poems, many of which evoke minimalism and consist primarily of the play between light and dark, and oppositions such as wet and dry, flying and falling, and life and death. “¿Y esa luz? / — Es tu sombra” (And that light? / It’s your shadow) (lxxiii).

While there are many references to Catholic traditions (Ash Wednesday) and biblical characters, the dominant metaphors evoke a general daimonic, animistic representation of physical elements of nature where the inanimate suddenly possesses the power to impart soul-igniting sparks and then revert back again (the body becoming nature), as in XXXII: “—¿Qué haré con esta chispa que se creía sol, con este soplo que se creía viento?” (— What will I do with this spark that believed itself the sun, with this breath that thought itself the wind?)

James O’Connor’s English translation, presented en face, is not doggedly literal but instead supports the transformational elements of Loynaz’s work. His approach reinforces the remarkable fluidity of her phrasings, which have a refractive nature, giving rise to multiple potential translations, each with subtle metaphysical shadings.

The final section, Melancolia de otoño (Autumn melancholy), moves with a neoplatonic fervency that observes changes in the beloved, not simply within or in elements of nature. The result is satisfying and triggers self-reflection.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list

More Reviews

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Umami by Laia Jufresa

Laia Jufresa. Trans. Sophie Hughes -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Eva Sleeps by Francesca Melandri

Francesca Melandri. Trans. Katherine Gregor -

-

-

-

-