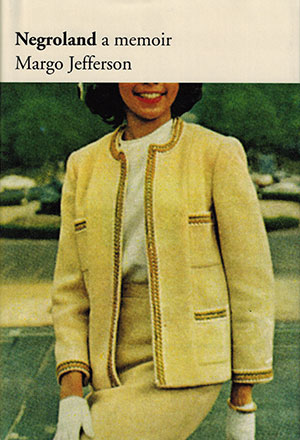

Negroland by Margo Jefferson

New York. Pantheon Books. 2015. 256 pages.

New York. Pantheon Books. 2015. 256 pages.

Margo Jefferson, acclaimed journalist and critic, has written a tour de force on the black privileged class. Hers is an artful and complicated memoir that achieves what countless other accounts of the black privileged class (fiction and nonfiction) have not been able to do with success. (Dorothy West’s account in The Living Is Easy is somewhat sentimental in the sheer awe the narrator has of the mother figure, and Lawrence Otis Graham’s account in Our Kind of People is a bit gratuitous.) Jefferson manages an honest yet balanced account of a class of people who have been pitted (in perception and sometimes in actuality) against the masses since the African’s abduction and forced enslavement in North America and the Caribbean.

The work begins with a definition of Negroland: “a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty.” Hence, Negroland is as much a place as it is a state of mind. Laced with descriptions of complicated housing and exclusionary practices and comportment and social commentaries, Jefferson’s narrative offers a thorough examination of the topic. In short, she is able to inspire sympathy and a sincere desire to understand the region’s ethos.

The brilliance of Jefferson’s approach in the work is manyfold. First, she manages an often-dispassionate chronicle of the historic rise and proliferation of the privileged class and its service to African American causes (racial uplift). Second, she alters her point of view (from first to third person) during times in which she might have otherwise lapsed into vitriolic attacks or sentimentality. Third, she is a master of verbal dexterity and the turning of a phrase. Consider Jefferson’s revision (appropriation of a well-known passage) of Frederick Douglass’s famed words when he overcomes the mental shackles of slavery; she writes, “Let us see how slaves, male and female, become social arbiters and leaders”—of which Douglass himself became one. Fourth, her command of African American, American, and British literature is inspiring and useful in much the same way readers are able to glean Azar Nafisi’s world through her use of literary classics in Reading Lolita in Tehran. Fifth, her first-person accounts of involvement in the peace, civil rights, women’s, and gay and lesbian movements are useful historical additions.

An additional and unexpected perk is the treatment of the mother figure who in Jamaica Kincaid’s world can be a willing participant in the oppression of their female children. The mother in this work is complex, formidable, resourceful, and above all the heroic connection to the survival of the female child, even during rebellious periods of childhood. Jefferson explains, “Negroland girls couldn’t die outright. We had to plot and circle our way toward death, pretend we were after something else, like being ladylike, being popular, being loved,” so as to avoid “matricide”—destroying the good reputation her mother, her grandmothers, and her grandmothers’ grandmothers had fought for since slavery.

Jefferson’s work is memoir, economic history, literary history, literary criticism, cultural critique, and a coming-of-age story neatly packaged for consumption. It recalls the literature of Zora Neale Hurston (the character Mrs. Turner in Their Eyes Were Watching God), the works of Dorothy West, and Andrea Lee’s Sarah Phillips in its examination of the women who either perpetuate or rebel against the privileged class.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list

More Reviews

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Umami by Laia Jufresa

Laia Jufresa. Trans. Sophie Hughes -

-

-

Eva Sleeps by Francesca Melandri

Francesca Melandri. Trans. Katherine Gregor -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-