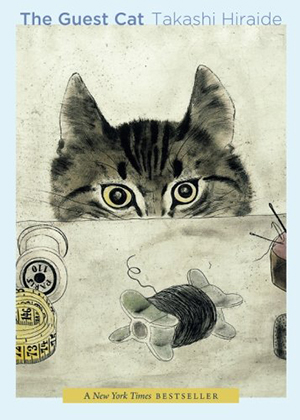

The Guest Cat by Hiraide Takashi

Eric Selland, tr. New York. New Directions. 2014. ISBN 9780811221504

The Guest Cat is, at its heart, a novel of loss, told in sparse, precise prose unencumbered by sweeping rhetorical flourishes or complex figurative language concerned more with its own cleverness than with the flow of the narrative. In this, many may see the poetic side of Hiraide (b. 1950), for he is better known for works in that genre than fiction, of which The Guest Cat is his first effort. The novel aligns itself comfortably with the long-established Japanese literary tradition of the “I-novel,” in which the protagonist is a thinly disguised simulacrum of the author and the subject of the work the trials and tribulations currently afflicting the writer.

The Guest Cat is, at its heart, a novel of loss, told in sparse, precise prose unencumbered by sweeping rhetorical flourishes or complex figurative language concerned more with its own cleverness than with the flow of the narrative. In this, many may see the poetic side of Hiraide (b. 1950), for he is better known for works in that genre than fiction, of which The Guest Cat is his first effort. The novel aligns itself comfortably with the long-established Japanese literary tradition of the “I-novel,” in which the protagonist is a thinly disguised simulacrum of the author and the subject of the work the trials and tribulations currently afflicting the writer.

While certainly not as maudlin and repetitive as many of the exemplars of this mode, Hiraide’s novel is structured as a collection of writings the author put together to help understand why he and his wife feel so attached to the titular cat, Chibi, and how that attachment affects their shared life after Chibi’s sudden death. The author and his wife are still young, live in a rented outbuilding on the grounds of a much larger estate, and are struggling to make ends meet after the protagonist quit his job to devote himself fully to writing. The cat gives some semblance of meaning to their lives, and its death parallels other deaths—the emperor in 1989, and their landlord—that affect the couple emotionally and concretely.

Although the novel reads quickly—Selland’s translation is engagingly fluid—and offers moments of insight through unexpected juxtapositions, the loss felt by the couple is mirrored by the sense of incompleteness with which readers are left at the end of the story. One cannot help feeling that the novel had aspirations toward being a novel of love, but the love represented in its pages is, ultimately, a shallow one. This does not doom the work, but that absence of depth contributes significantly to the feeling of dissatisfaction that a greater connection to the protagonist and his wife exceeded the power of the prose.

Still, The Guest Cat is a pleasurable enough diversion that, rather surprisingly, lingers long after the book has been set aside. Indeed, the conceit of a neighbor’s cat who happens to spontaneously “adopt” a different “owner” is really little more than an expedient for extended metaphysical ruminations on the vicissitudes of life in the face of uncertainty. This is a situation not unfamiliar to most readers, and it is, perhaps, the greatest strength of this slim novel, for no answers are provided: only hints of what may be possible.

Erik R. Lofgren

Bucknell University