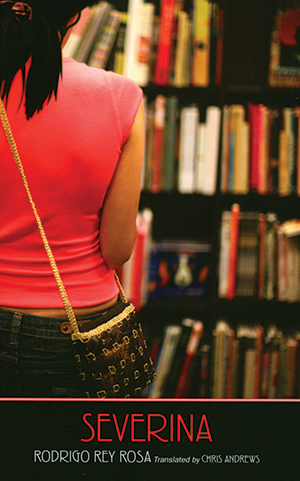

Severina by Rodrigo Rey Rosa

Chris Andrews, tr. New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2014. ISBN 9780300196092

Severina is a multifaceted novel that exposes the complicated maneuvers which make up the dénouements of a nontraditional love story. Set amid the shelves of a local bookstore, the narrator, part owner of the store, observes a beautiful young woman surreptitiously shoplifting his books—not just any books, either, but specific, high-end books that would bring a good profit to the store. The bookstore’s name, La Entretenida (The Entertained), is a most descriptive name as it appropriately reflects the plot, the characters, and the culmination of the story in an ironic play-on-words. There is little that could be described as “entertaining” among dusty tomes on even dustier shelving units, unless, like me, you are an avid book reader. For people like me, there is nothing quite as fulfilling as wandering around a shadowy store, shelves reaching from floor to ceiling, dust motes gently tickling nose and eyes causing sneezes and sniffles, riffling through old books. That also appears to be the raison d’être of the book-lifter and her grandfather.

Severina is a multifaceted novel that exposes the complicated maneuvers which make up the dénouements of a nontraditional love story. Set amid the shelves of a local bookstore, the narrator, part owner of the store, observes a beautiful young woman surreptitiously shoplifting his books—not just any books, either, but specific, high-end books that would bring a good profit to the store. The bookstore’s name, La Entretenida (The Entertained), is a most descriptive name as it appropriately reflects the plot, the characters, and the culmination of the story in an ironic play-on-words. There is little that could be described as “entertaining” among dusty tomes on even dustier shelving units, unless, like me, you are an avid book reader. For people like me, there is nothing quite as fulfilling as wandering around a shadowy store, shelves reaching from floor to ceiling, dust motes gently tickling nose and eyes causing sneezes and sniffles, riffling through old books. That also appears to be the raison d’être of the book-lifter and her grandfather.

There is something refreshing about this novel, set as it is in a “real” bookstore. There is something ageless and reassuring about the physicality of holding actual, printed books in a world that is increasingly inhabited by books on electronic Kindles, Nooks, or iPads. For a “traditional” (paper book) reader, the ambience inside La Entretenida is comforting and familiar. The poetry readings that take place once per month might not be within our scope to recognize, but just being inside the holy-of-holies of a bookstore gives us a sense of days gone by.

The plot is somewhat convoluted as the bookseller falls in love with the book thief and allows her to continue stealing his stock until he confronts her, follows her to her lodgings, watches for her day by day, sees her leaving the country via plane, and waits for her to return. When she does return some months later, he secretly becomes a lodger in her pension so that he can be near her. He is confused by the man she lives with, who, he is told, is her husband, then her father, and eventually he discovers the man—Otto Blanco—is actually her grandfather. The plot complicates itself when Mr. Blanco has a stroke and the bookseller takes him and his granddaughter to live in his apartment. Eventually, the old man dies, either naturally or by his granddaughter’s hand, and she and the bookseller decide to bury him in the desert as neither Otto nor Severina are legal residents of the country, and it would prove complicated to explain their presence in the country, let alone the death of one of them by natural means or foul.

The twists and turns of the incredible story leave the reader awestruck, waiting for some kind of cataclysm to befall the lovers. Rodrigo Rey Rosa has set this short piece in his homeland of Guatemala, yet there is little to suggest that locus other than the suggestion of pervasive sociopolitical difficulties, which the narrator alludes to but does not fully explain. So, does the novel end happily? I suggest you read it and discover the conclusion for yourselves. It is worth the effort. I certainly look forward to reading more of Rey Rosa’s stories, and so will you after Severina.

Janet Mary Livesey

University of Oklahoma