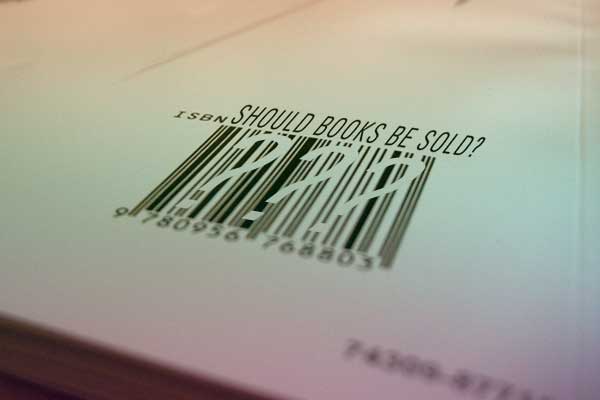

Should Books Be Sold?

With bookstores and the publishing world in crisis, could ads within books be the answer? Victoria’s Secret in Pride and Prejudice? Abercrombie & Fitch in On the Road? Ilan Stavans looks at what we might learn from both Homer and Netflix.

I frequently ask people this question, in part because I want to inform myself but also because I am ambivalent. I love books. I live and die by them. But I find myself buying fewer and fewer. And I know I am not the only one. The book industry is in crisis.

In my view, we are witnessing the end of “the book era.” What lies ahead? A different understanding of what that artifact is. Dictionaries today still define a book as “a written or printed work consisting of pages glued or sewn together along one side and bound in covers.” Needless to say, no one takes that definition seriously.

And yet, we still have books: different kinds of books, books that don’t look like books, books that behave like anything but books. People aren’t consuming them, though, at least not the way they used to. Would it make sense to make books available with advertisements? Would that change the nature of the game?

A time of crisis is a time of reckoning: we should ask questions and look for answers.

Let’s start by acknowledging the obvious: literature is a business. As an author, I make my living through it. The sale of books sustains not only us but a larger battalion of people, from editors to translators, from publicists to marketers—and publishers, too, even though publishers seem to be going the path of the dinosaurs.

Books were not always perceived as a mass-market commodity. That view is relatively recent: it dates back to the Enlightenment, with the advent of industrial capitalism, when intellectual property and the idea of authors as sources of wisdom and entertainment became commonplace.

For it is no secret that the book industry—in the United States, at least—is in deep trouble. Supply is far bigger than demand. In other words, the number of books released annually is on the ascent while the number of buyers is on the descent. Is there a way to reverse this trend? Is it that the book as a conduit of storytelling is dying out, or might the problem be with the concept of selling books?

Books were not always perceived as a mass-market commodity. That view is relatively recent: it dates back to the Enlightenment, with the advent of industrial capitalism, when intellectual property and the idea of authors as sources of wisdom and entertainment became commonplace.

Homer, the ultimate classic and an ever-attractive commodity among publishers, isn’t an author, as there is no proof such a person existed. Instead, Homer is a stand-in to describe an oral tradition about the Trojan War and the return of Odysseus to Ithaca. At some point in history, that tradition was fixed in hexameters on a page and passed down to us now. Who owns those hexameters? The Greek people. Or, more broadly, Western civilization. Or, since that concept is contested today, I should say every reader who partakes in Homer’s narrative.

Yes, the reader as owner. Naturally, this isn’t an attractive idea for publishers. They like to think of themselves as caretakers of the classics. They release new editions of The Iliad and The Odyssey, they translate them anew to achieve a single objective: to make money. Yes, they might be altruistic, but the goal is always the same: profitability. In that sense, Homer isn’t different from the Bible: anyone can make money out of it. The same goes for other classics in the public domain: Dante, Goethe, Flaubert . . . Contrary to common assumptions, a book in the public domain can be a valuable commodity. In fact, it is more valuable than most titles under copyright. The challenge is to make the classics alluring as merchandise.

Similarly, my intention here is to reflect on what makes books not only available to large audiences but also sellable and, as important, profitable. At least the first part of that is the dream of democracy: to disseminate information in egalitarian ways. Again, that dream is a relatively late development. Books didn’t sell in large quantities in the Middle Ages, when they were mostly religious items in monasteries, although early examples of financial exchange, as Stephen Greenblatt and others have shown, date back to this epoch.

Market value became a fixture of the Enlightenment, as Don Quixote of La Mancha vividly shows: a fifty-something hidalgo wastes his limited income on chivalric novels—an unproductive endeavor according to Cervantes’s ironic narrator. Cervantes himself didn’t make much money from book sales. Along the same lines, Shakespeare’s quartos became marketable only after his death.

In short, books were not sold for most of their history. Mass production and sale is only a recent development. Not selling them isn’t so inconceivable after all.

We have Johannes Gutenberg, and the invention of movable-type printing, to thank for giving birth to the age of the modern publisher as venture capitalist. Gutenberg is a hero despite himself because, for all intents and purposes, he didn’t think his invention was directly linked with capitalism. Nor did he portray himself as a promoter of democratic values. Instead, he was a practical man looking to solve an age-old challenge: how to make the printing process more agile, less cumbersome. His mechanical press made books an irreplaceable device, without which modernity is inconceivable.

A friend of mine often says that books are like food: they sell because people need to eat. True, we buy books because we hunger for information, for knowledge, for amusement. But in economic terms, books aren’t like food: you really don’t need them to survive. In fact, the need for them is dying out, at least in regard to the standard printed book, even though print is still approximately 70 percent of the market (if we talk about literature per se, the percentage is higher). Necessity is the mother of invention.

Books used to sell because people needed stories. They wanted new stories, stories that related to their lives. They also wanted to know about the past. And they were curious about the future. Books sold because humans are curious. But there are other means to satisfy that curiosity today, from TV to movies, from theater to the Internet. Books are in crisis today because they must compete against other, more tempting media. Hopefully, even as readership wanes, books will still be produced; because people will always hunger for this type of storytelling, for this type of private thinking process.

A printed book is a technological device. So is the iPad. Digital books have become attractive because they are easily transportable, because the reader is able to upload multiple stories on the same device, and because—voilà—they are affordable. However, the basic model of digital books is the same for printed books: a publisher puts one on sale and an interested reader buys it. If the book is appealing and—miracle of miracles!—lucky, it will sell well; if it isn’t, it will disappear from sight.

Are there other business models through which stories might reach readers in book format? Let’s think of different venues. I will start with commercial radio, Facebook, Twitter, and large segments of the Internet: they reach consumers not by asking them to pay but through advertising. Users respond because they offer an attractive proposition: stories that allow people to feel connected. All one needs is a radio, an iPad, or a laptop. Who pays the bill? Advertisers.

TV functions in the same way. Instead of paying ABC, CBS, or NBC, viewers buy merchandise advertised in commercials. HBO, Showtime, and other cable channels have pushed the medium to another realm: subscription TV. These networks do use some forms of advertising in their programs, but it is solely used to promote their own products. Other networks such as AMC, which showcases Mad Men, among other series, combines subscription revenue with more traditional forms of advertising.

In contrast, public radio and TV for the most part depend neither on advertising nor on subscriptions but on individual and corporate donations. These are juxtaposed with a basic funding package coming from federal, state, and local budgets making possible the basic services of those public channels.

How about selling literature through subscription? Or through a mix of subscription and ads? Netflix and Spotify successfully combine the two. Could books be produced in ways to create the passion of Game of Thrones? This model, by the way, isn’t that different from how Charles Dickens offered some of his meganovels in the second half of the nineteenth century: in serialized form, with chapters being released on a weekly basis in newspapers. Readers drawn to Dickens’s plot and style regularly bought newspaper copies. Magazines also use this strategy.

Film presents the same model, although perhaps with more chance of success today. Blockbusters are produced in Hollywood by private production companies ready to spend lavishly on an assortment of genres to recoup their investment. Smaller movies have minuscule budgets whose sources come from private entities. At times the combination of these two formulas allows for a modest movie to become a “sleeper.”

My point is that media thrives in a diversified market, one where manufacturing an item (a movie, a radio program, a cable miniseries) doesn’t always depend on a single investor’s deep pocket. In the book industry, cases abound of self-published titles where authors big and small, from Stephen King to debutants rejected by corporate editors, sidestep publishers in order to embark on the publishing adventure themselves.

As a society, we have already transformed—with considerable pain—our idea of a bookstore from a physical entity to a virtual one. Amazon.com is the principal provider. But here we face a substantial risk: the company has become a monopoly controlling not only prices but also business practices. On average, Amazon.com takes upwards of 30 percent of the price of every e-book sold, an amount that is actually lower than for print books, which is closer to 50 percent. This is roughly the same with Barnes & Noble. The company also forces the publisher not to sell the item at higher prices elsewhere. Plus, like other retailers, it doesn’t allow advertising inside the books. Since the majority of readers nowadays consume books through Amazon.com, the company de facto legislates the market. It also controls our freedom to sell.

What if we wanted to place ads in books? Shouldn’t we push the big transnational retailers to open up? What if instead of readers bearing the brunt, it was left to companies to place ads in books so that readers would get them directly and through the commercials compensate those companies with a profit? Or to sell them through weekly installments à la Breaking Bad? Interestingly, these days, a big part of the audience for these shows watches them online, bought from iTunes and such, without ads or a subscription. Could that be the route books take as well?

Granted, this idea of using ads in books sounds intrusive, even obnoxious. I myself hate it. I dislike watching commercial TV, in large part because of the ads. I’m a devoted NPR listener. Still, a good idea isn’t only about the pleasure it provides but about the venues it opens. When I watch HBO and Showtime programs, I use the mute button in my remote control to mitigate the presence of ads. Surely it is possible to imagine a similar scenario with books. Aren’t we able to do that with YouTube?

When I presented the model to some forty high-schoolers in Oxford with whom I spent a week reading the classics, their first thought was that I was a fool. I wanted them to visualize a copy of Pride and Prejudice with a Coca-Cola ad in the inside cover, a Victoria’s Secret ad in the back, and maybe a series of smaller ads at the start of each new chapter.

The teenagers spoke to the intimacy they feel when reading and how it would be spoiled. I asked them if they don’t feel intruded upon when watching The Walking Dead. No, they said. They’ve gotten used to the ads. So—I added—could you get used to ads in Leaves of Grass?

I showed the high-schoolers a paperback copy of Fahrenheit 451 I happened to have with me: it featured an ad for other covers of books by Ray Bradbury as well as the publisher’s website and, in the back matter, questions for reading clubs and a list of other world classics the reader might be interested in, from Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Aren’t those ads also?

I tempted the kids to reflect on the type of subliminal product-placing advertising Hollywood has accustomed us to, as in the case of a James Bond movie filled with BMWs and Alfa Romeos. What if we allowed similar ads in novels? Truth is, we already do: authors have considered product-placement possibilities in their work as a form of revenue. The jury is still out when it comes to results, yet no one appears to be angry enough to refuse to buy a good read that endorses this model.

One of the most attractive, fastest-growing items in the digital publishing industry today is the “single.” Singles are quick reads of between five thousand and thirty thousand words. One competitor even tells people the approximate number of minutes—between half an hour and 120 minutes—these nanobooks require. The model sells not only because the majority of people don’t have time to read but also because they see reading as a chore. Interestingly, their price ranges from $1.99 to $2.99, which means profit is minuscule unless a vast quantity is sold. Thus, publishing large numbers of singles, books that require limited editorial labor, broadens the profit margin.

Like most full-length books, a vast number of singles sell only a couple of dozen copies. Should they be free, then? What if free singles were stuffed by the publisher with ads for other titles by the same author as well as other titles in general? Even better, what if instead of selling the single at $1.99 the item came with paid advertisements and was given away for free?

But why would Abercrombie pay for an ad in my copy of On the Road? Because it might reach a desirable segment of consumers, as it does with magazines, which, by the way, are also in a dire business. Readers of Kerouac are the audience the company depends on. That is the same reason corporations advertise on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media: to create taste patterns, to invest in the mind, not only in the looks, of its clientele. Corporations aren’t only about profit. They are also about image.

Some small publishing houses such as Wave, Open Letter, and Ricochet are taking the subscription route seriously, albeit in the print, not necessarily the digital, world. These and other electronic-only ventures (like Frisch & Co.) and electronic-friendly publishers deserve attention, which means experimentation is taking place. Ugly Duckling Presse, for instance, offers all its print titles online for free. Behind the strategy is the idea that fans will support writers by other means.

I am involved with Restless Books, a digital-publishing venture seeking to address the dire need English-language readers have for translations of world-class literature from around the world. One of its objectives is to make books—not only poetry but novels and nonfiction—available in two or more languages to readers everywhere.

And in Japan and South Korea, there are publishers releasing books on Twitter or stories designed specially for iPhones, not to mention the countless websites devoted to bringing books exclusively online. How do they make money? Through ads, donations, and, sometimes, plain charity.

It is important to keep in mind another route: the author as personality, making a living from speaking engagements. The crowd-sourcing events website Togather is a fine example of how bookselling might look in the future. This begs a comparison with the music industry, where advocates for free music argue that more widely distributed titles would garner more fans for artists and thus higher attendance at concerts and sale of merchandise.

To conclude, my feeling is that the health of the publishing industry—or some semblance of it!—can only be sustained by a hybrid approach. The book as merchandise might not have an expiration date if we learn to see its marketability in a flexible fashion. Human curiosity is innate to our existence. But paying cash for an item isn’t.

As long as we live in a capitalist system, books will always be sold, although the idea of what constitutes a book as well as what we understand as a sale are undergoing dramatic transformations. Decades ago, I had a theater teacher who lived by a single mantra: don’t give the public what the public wants; instead, teach the public to want something different. If the public likes it, if it makes it feel satisfied, it will not notice the difference.

Amherst College