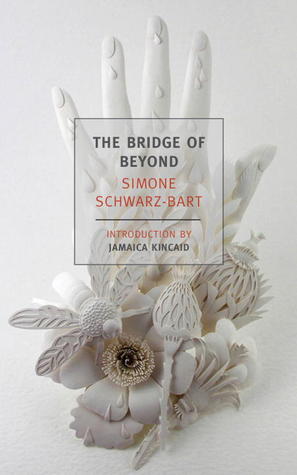

Editor’s Pick: The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwarz-Bart

The Bridge of Beyond

The Bridge of Beyond

Simone Schwarz-Bart, Barbara Bray, tr.

New York Review Books Classics, 2013

Born in 1938 on the southwest coast of France, Caribbean writer Simone Schwarz-Bart spent her childhood in Guadeloupe, an island in the Lesser Antilles. She later studied in Paris, where she met and would marry the French writer André Schwarz-Bart, with whom she has co-authored a number of works. She has traveled extensively, and has also written another novel and a play. In this new edition of her best-seller The Bridge of Beyond, her narrative and Barbara Bray’s 1974 translation from the French both hold up well, confirming the novel’s status as a tour de force of Caribbean literature.

Originally published in French as Pluie et vent sur Télumée Miracle (1972), Bridge is part chronicle, part ballad, and part fable—a rhythmic fictional autobiography written in the voice of its heroine, who tells us of life in the Antilles at the turn of the last century. For Schwarz-Bart, “the essence of Guadeloupe will always be the most oppressed and proudest Negroes of the island.” Thus in this work, the narrator-protagonist is Télumée Lougandor, a character drawn from the author’s memory of an old peasant woman from the Guadeloupian village where Schwarz-Bart grew up with her mother and sister.

Approaching the end of her days, Télumée tells the story of her life, a narrative nearing epic proportions, at times a mythicized genealogy of the Lougandor women. Endurance without male support, one of slavery’s legacies that haunts the text on every page, is a main thread of this genealogy, and two cumbersome questions reverberate throughout the text: “What does it mean to be a woman?”—and, “what does it mean to be a slave?”—questions that seem to echo each other.

In her introduction to this edition, award winning Antiguan-American novelist Jamaica Kincaid writes that the novel is “an unforgettable hymn to the resilience and power of women.” Indeed, when trying to describe what exactly lives within the pages of Bridge, I found myself settling with the phrase, “it’s the stuff that the blues are made of.” With a “languorous sense of ease,” as Paul Theroux comments, “it is poetical but not always clear.” The effect of Bridge is intoxicating, and not just because it nurses familiar blues riffs from my own American heritage—its heady prose renders a vivid, full-bodied account of life in the Antilles.

Bridge, says Kincaid, “tugs” into the “painfully personal,” into the delights and grief of community. Theroux remarked that its glorious prose veers “dangerously close to delusion”; yet despite young Télumée’s testimony that “some look on the sun while others disappear into the night,” the text and its characters don’t remain adrift in sadness. By some means, the Lougandor women “rely neither on happiness nor on sorrow for existence, like tamarind leaves that close at night and open in the day,” leading Télumée to declare of her life:

There weren’t two separate parts—they had taken place in one and the same person, and it was well, and I rejoiced at being a woman.

This is an infinite, celebratory novel, containing multitudes in the space of each rich sentence—a masterpiece of Caribbean literature that certainly deserves the badge of the classic.

Sara Wilson

Editorial Assistant