Turning Thirty

On the eve of his thirtieth birthday, the narrator recounts three near-death experiences and his journey from Morocco to France. With nods toward Dostoevsky and Genet (echoing the Lazarus scene between Raskolnikov and Sonya in Crime and Punishment), he experiences a crisis of existential vertigo.

I’m afraid.

I’m not afraid.

I’m strong, very strong, indestructible.

As a child, adolescent, I was sick. Sick but alive.

Today, in Paris, I’m alive but sick.

I feel weak. I’m no longer able to sleep at night, so I think about Isabelle Adjani, about her singing voice. I’m ashamed, having spent years in France, seven years already, that Adjani’s voice has replaced my mother’s in my head. No, no, it’s not that I’ve forgotten her, my mother, no, it’s simply that everything in me comes from her, everything that I am is marked by her, her indelible imprint. I suffocate.

I am my mother with the voice of Isabelle Adjani murmuring, humming a song. “Pull marine.”

•

I died. Three times.

The first time.

In the middle of a summer afternoon, in Salé, in my neighborhood, Hay Salam, the angel of death took my soul, but only for a few seconds. I saw myself from above, a sleeping body, peaceful and blue. Did he have pity on me, this terrible white angel? Did God make a mistake? They ended up giving back my anxious soul at the end of those few seconds during which they discussed my fate in front of me, my days and years yet to come, my fate despite myself. And they departed for other destinations. I opened my eyes. Everyone at home was taking a nap, except my father. He was in my mother’s place, at my bedside. He had understood, seen what had happened. He gave me his hand, I took it, I got up, and we went out into the streets, barefoot, to lovingly reacquaint ourselves with life and light again.

The second time.

I was playing alone at a dead-end of Block 15. On the cusp of adolescence and already abandoned by my childhood friends. Not knowing any better, I touched a high-voltage electric pole. Electrocution. I lost consciousness. It was instant blackness, beyond myself, without memory. For how long? I don’t know. When I came to, I saw that the entire neighborhood (dozens and dozens of people, a crowd) was in our house. Crying for me. Even screaming for me. It was unfair, departing at such a young age. I got up suddenly. A man said, “Quickly, quickly, wash his feet, hands, and face with hot water . . . quickly, quickly . . . but not with cold water, mind you!” An ambulance arrived a bit later. The crowd of neighbors carried me carefully, slowly. They took me to Avicenna Hospital in Rabat. I was proud that I was going to be cared for in the most important hospital in Morocco. I was happy, for once people were truly going to believe me, take my strange body and its maladies seriously. My heart and its beating greatly intrigued the doctor, a white-skinned man, a Fassi. He took an x-ray, put his hand on my chest, on my heart, for a long, long time, he saw something that was happening in me that I had never had access to, he understood my body differently than I did, which intrigued me. He caressed my cheek. Played with my hair. And, before leaving, he leaned toward me and murmured a secret in my ear. He said, “Between the two of us . . . you have a strong heart, a heart for life. . . . You will live a long time, my son! Get up!” He saved me, and I still remember his name quite well: Doctor Salah El-Hachimi.

The third time.

To get away from Hamidou, with whom I was in love although he didn’t know it, I went to risk my life on the other side of the sea wall of Rabat’s beach, toward the wild, pitiless waves. I stepped on a large, slippery rock. An enormous wave immediately plucked me with sweetness and violence to transport me to another world in its company. I didn’t close my eyes, I was conscious, and in this movement toward the depths of the ocean and of death, I understood, I saw.

. . . Hamidou wasn’t worth the effort, this sacrifice, it wasn’t worth going to the trouble of changing his opinion about me. He didn’t see me. I didn’t exist for him. He had told me a few minutes beforehand: “You have normal skin, it’s missing something . . . how strange!” Hamidou didn’t love my skin. He didn’t love me. I didn’t believe in loving myself. Love, I read somewhere, is often criminal. . . . I was still with and inside the wave. Just before it smashed onto the rocks, I don’t know by what miracle, I grabbed something—a branch, I think. I grabbed it, held on, and waited for it to pass, to subside. Then I got out of the water. I was on the sea wall, walking. It was the month of August. The souk was on the beach. And there I was all bloodied, wounded in the chest, the arms, the knees, the nose. Blood red. People stopped to look at me. I wasn’t afraid, didn’t think I looked ridiculous, I wanted Hamidou to see me that way, for him to panic, to take pity on me, to regret his indifference toward me, to cry, to beg for forgiveness for the wrong he had committed against me, to be touched, to love me, finally. . . . And at that instant, instead of seeking revenge, I would have said to him: “Goodbye . . . farewell . . . I finally belong to myself, remain with myself . . . I’m alive despite you, without you, far from you. . . .”

•

Two years ago, in Paris, Tristan came into my life. Today he’s almost six years old. A little man. The little prince. I pick him up outside his school four days a week. I take him back to the large house, as he calls it, a huge apartment next to the Blanche subway station. I play with him. I make him do his homework. I give him his bath: he is completely naked before me, unself-consciously nude. Together we watch cartoons, The Lion King, Finding Nemo. Sometimes I tell him Moroccan stories, about my terrible young childhood, I teach him words in Arabic. We pretend to fight, sometimes for real. We cry, scream, mock each other, kindly, meanly. Each day he gets a little bigger, grows rapidly like a flower that one waters with care, with love. He grows before my astonished, wondering, happy gaze. Even when he annoys me, even when he acts like a little macho man, Tristan remains a little sun for me. The Parisian sun that will never burn my skin.

I repeat in my head what he’ll say to his friends later, perhaps to his children: “When I was little, my babysitter was Moroccan, his name was Abdellah.” Three hours a day, I play a small role in his life, in his future, and that makes me proud in spite of myself. I feel like I’m accomplishing a mission with him. I accompany him.

Tristan is not my son. Tristan is a little angel who sometimes cries like that, for no reason, he cries in my arms, I console him tenderly, but I never know about what. I’m envious of his innocence, his pure outlook on the world. He doesn’t know. He still doesn’t know. Ignorance is bliss!

There are some truths about me and about the world that I hope are never known. I reflect too much. I complicate everything, everything. I think, I think, a permanent bottleneck in my head. Ideas and images I don’t know what to do with.

I’m so tired of myself, of being me in this hurried life. I look for something that will come, that is slow in coming. I should take a step, just one more, I should renew myself, find or summon the energy. I have plans: they tell me I always must have some in order to find a daily rhythm, a connection between the visible and the invisible.

The meaning of life, of my life, escapes me.

Others seem to be happy. Are they truly happy? What makes them happy? Why do they know where to go and I don’t?

My name is Abdellah: the slave, the servant of God. I freed myself from Morocco’s constraints (but really?). All that remains is to escape myself.

I looked for loneliness. I found it, and it’s insufferable. I’m permanently myself, unable to forget who I am. My consciousness of my being has accrued over time. An anguished consciousness. I know what’s happening inside myself, my beating heart, beating unevenly on occasion, my ears whistling, blood sometimes hot, sometimes cold, the air that produces a strange music while entering and leaving my nostrils, my cracking bones, my changing skin, the feuding ideas in my head, the jostling images in my eyes, and my sexuality that cries out its desire, yet I do not obey it.

The past few months, I’ve been haunted by the idea that I might go crazy someday. That seems easy to me today, to switch over to another mind-set and completely forget its other skin. I always loved the insane ones in Morocco. They seemed to be in harmony with the country. Are they still?

Death and madness possess me.

Last July, Dostoevsky and Genet became my favorite writers once again. They speak to me. We’re afraid together. We go hand in hand toward life, tormented and sometimes miraculous, together, alone, each in his own terrible and delicious solitude. They can do nothing for me. I am possessed by them.

I must change my first name. Karim? Farid? Saïd? Habib? I am neither generous, unique, happy, nor loving. Wahid, then? Yes, definitely, at this moment I am Wahid, solitary and proud, susceptible and unhappy.

I’m headed toward something in Paris, that luminous and exceedingly quiet city. I walk toward my fate, and each day I have the impression that I’m not deciding anything. I’m not my own master. I took a step, coming to Europe, and I was swept up in the infernal movement of Western time. Everything passes quickly, all is quickly forgotten, everything is orderly, apparently clean, everything in its place. Everything is parceled out.

Today, I know, I pay the price.

It began with a slight despondency, nothing serious. I got over it, I had to get over it. Now it’s started again, it’s coming back but in another guise: crises of anguish, of panic. A red image, a taste in my mouth, a hemorrhage in my head. I anticipate falling. I see myself fall, a motionless body in the Parisian street that passersby pay no attention to. I wait and wait. But I don’t fall. I’m still upright. I don’t know where my strength resides in me, I don’t know how to locate, guide, channel, define it.

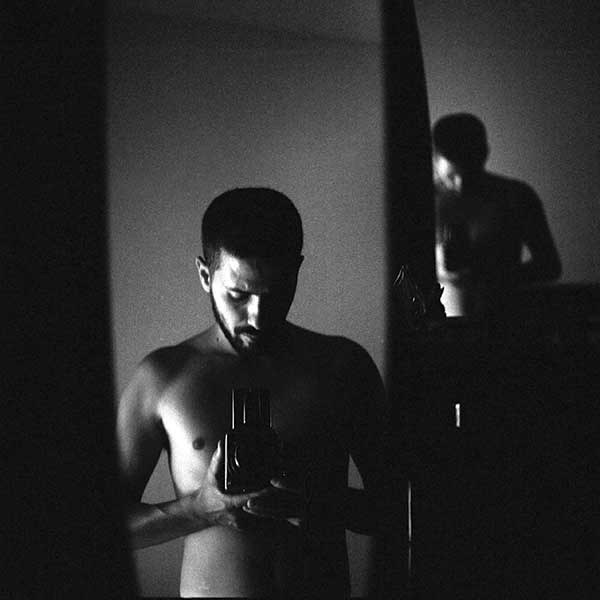

The past few months, I’m no longer myself, I don’t recognize myself. I look at my face in mirrors, I look at my feet, my hands, my nails, my hair, my skin, and each time I ask myself the same question: Whose are they?

In psychiatry, what has come over me, is happening to me, has an exact name: depersonalization.

Does becoming an adult mean being able to find the medical name for one’s neuroses?

•

Tomorrow is my birthday. I’ll be thirty years old. This I’ve decided: I’m going to enjoy looking at myself in the mirror, I’m going to masturbate deeply, aroused by my image. Thus will I be able to rediscover myself, perhaps, body and soul creating anew the sacred union of my being.

Tomorrow I’m going to be on another path, a way that leads to this other number: thirty-one.

I dream, I close my eyes for a few seconds, I close them violently, masochistically. I go blind. I open them, I’m elsewhere, myself in another age, older, in an indefinable time. This other world will certainly exist in my forties. I imagine it. Each day I create a long movie about it.

I’ve known this since my childhood. I’ll be a forty-year-old man. Not sooner. Forty years in order to finally say, comforted, lighthearted, perhaps free: i am the man of my desires.

Paris

Translation from the French By Daniel Simon