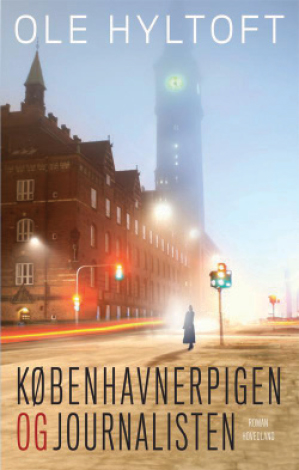

Københavnerpigen og journalisten by Ole Hyltoft

Højbjerg, Denmark. Hovedland. 2013. ISBN 9788770703581

Ole Hyltoft’s Copenhagen trilogy (see WLT July 2006 and January 2008) spans an entire century. In the first volume the milieu is that of a poverty-stricken working-class district around 1900. The second volume describes a series of dramatic events during the German occupation of Denmark (1940–45). With the present and final volume, Hyltoft presents his readers with some of the most pressing social and political problems in Denmark today. The three novels are held together by their large gallery of characters as well as by the author’s enamored description of the Danish capital itself.

Ole Hyltoft’s Copenhagen trilogy (see WLT July 2006 and January 2008) spans an entire century. In the first volume the milieu is that of a poverty-stricken working-class district around 1900. The second volume describes a series of dramatic events during the German occupation of Denmark (1940–45). With the present and final volume, Hyltoft presents his readers with some of the most pressing social and political problems in Denmark today. The three novels are held together by their large gallery of characters as well as by the author’s enamored description of the Danish capital itself.

The plot centers both around the life of the high-ranking public servant Vini Lauenborg—the Copenhagen girl of the title, the third generation of an artistic family of painters and architects whose colorful lives are depicted in the previous novels—and around the everyday life and work among journalists employed with a major Danish newspaper, among them the influential Christmas Vingaard, another major character of the novel.

Around these two characters, Hyltoft constructs two plots: one develops around two love stories; the other focuses on contemporary politics and journalism–themes the author has dealt with critically in several of his previous novels and essay collections. His Danish audience will have no problem identifying the newspaper with the prolific Danish daily Berlingske Tidende. Thus, his novel can also be read as a roman-à-clef, and Hyltoft’s readers can enjoy his humorous and strongly satirical portraits of public figures and journalists, most of them corrupt, vain, and opportunistic.

However, satire is not Hyltoft’s principal aim. The newspaper and its employees become part of a precise analysis of one of the most urgent political issues in present-day Denmark: the clash between Danish society, with its democratic values, and a militant, often anti-Semitic Islamism among immigrants. The novel’s two plots converge in Vini’s fight against having a planned exhibition of her grandfather’s paintings and her father’s drawings—including that of a Jewish cultural center—replaced by an exhibition of Muslim miniatures. The dramatic events climax as various attempts at stopping Vini escalate into treacherous assaults and an act of terrorism, when a letter bomb kills the newspaper’s Jewish reporter.

But equally important to Hyltoft, and perhaps even the main theme of his novel, are the two love stories—one between Vini’s ninety-year-old father (the portrayal of him is truly grand) and a woman he has not seen since World War II, and one between Vini and the journalist, Christmas—love stories reaching across several generations and social boundaries. Here it becomes obvious that first and foremost Hyltoft’s novel is a fervent advocacy, indeed a glorification of solidarity not only with the country’s traditions and values—including that of free speech, which the author sees as threatened—but even more so among compassionate human beings at all times. Through this message, Ole Hyltoft remains true to the major concerns expressed in his entire oeuvre, making him one of the most important representatives of Danish humanism.

Sven H. Rossel

University of Vienna