The World Through the Eyes of Angels by Mahmoud Saeed

Samuel Salter, Zahra Jishi, and Rafah Abuinnab, trs. Syracuse, New York. Syracuse University Press. 2011. ISBN 9780815609919

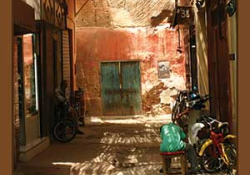

A prolific writer with nearly thirty novels and short-story collections to his credit, arrested and imprisoned in his native Iraq more than once because of those works, and now living in exile in Chicago, Mahmoud Saeed has produced a plangent and tender tribute to the Mosul he knew in the 1940s and ’50s. The author’s preface narrates the book’s origin: Saeed, saddened by the present violence and destruction in his homeland, observes in happy and peaceful Tijuana a young boy running barefoot on an errand. The sight reminds him of his own poverty-stricken childhood in a city where adherents of the three monotheistic faiths lived harmoniously together, and awakens the desire to write a book that would “serve as a living witness to a people [now] fated to walk in bitter darkness.”

A prolific writer with nearly thirty novels and short-story collections to his credit, arrested and imprisoned in his native Iraq more than once because of those works, and now living in exile in Chicago, Mahmoud Saeed has produced a plangent and tender tribute to the Mosul he knew in the 1940s and ’50s. The author’s preface narrates the book’s origin: Saeed, saddened by the present violence and destruction in his homeland, observes in happy and peaceful Tijuana a young boy running barefoot on an errand. The sight reminds him of his own poverty-stricken childhood in a city where adherents of the three monotheistic faiths lived harmoniously together, and awakens the desire to write a book that would “serve as a living witness to a people [now] fated to walk in bitter darkness.”

The World Through the Eyes of Angels triumphantly succeeds in recapturing lost time. In a dozen interlinked short stories, sometimes incorporating meditations upon memory and the past, a sensitive and intelligent boy lives through childhood and adolescence. Although Saeed insists upon the harshness of his young alter ego’s life—he is obliged to run errands in Mosul’s searing heat and subjected to physical abuse at the hands of his elder brother—the stories’ tone, if anguished at unpredictable loss and untimely death, is still gentle, brooding, nostalgic.

The most important stories deal with the three women the protagonist loves and loses. The Muslim Selam, living penniless with her sick mother, offers the boy water. An idyllically innocent relationship ensues, which comes to an abrupt end when girl and mother disappear without warning. (In the closing paragraphs of the book, the narrator expresses grief that his younger, oblivious self took no action to save the pair: Selam must have lived, or died, wretchedly.) The opulent beauty of the Christian Madeleine teaches him about the sexual power of women; her end reveals the plight of those who lose their virginity outside marriage in a traditional society. The Jewish Somaya, never forgotten, is doomed to an early death because of bone cancer.

The narrator, in addition to lamenting his failure to help Selam, feels guilty that he did not record the irreplaceable knowledge of Mosul’s history possessed by an illiterate storyteller. Saeed, having here preserved in literary aspic the life of Mosul’s poorer sections from seventy years ago, need have no such regrets.

M. D. Allen

University of Wisconsin, Fox Valley