Translating Ch’ol: A Bridge Between Linguistics and Poetry

TO VIST THE Ch’ol poet Juana Peñate Montejo’s house in Chiapas, Mexico, requires several flights, at least three van rides, and hitching a ride on a co-op pickup truck that winds its way up an unpaved road to the town of Tumbalá. Coffee and corn fields pepper the valley below. If you ask for directions to the “poet’s house,” anyone will be able to tell you. Peñate is well known in the community and in Chiapas, since she won the Premio de Literaturas Indígenas in 2020 for her collection of Ch’ol poems, Isoñil Ja’al (Dance of the rain). Ch’ol is a living Mayan language spoken by a quarter of a million people in southern Mexico as well as diasporic communities across North America. The Mesoamerican Mayan language family, with speakers of over seven million, comprises about thirty languages, each with its own locality and cultural traditions. They are as distinct from one another as English is from German.

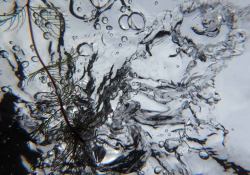

In Peñate’s poetry, the body-self is engaged with, and affected by, the landscape, the weather, and the spirits. Tones shift from declaration to plea, tentative to self-assured. The territory, internal and external, is vast. Peñate constructs and claims spaces in the world, as a poet and a woman. As translators of her poetry, we dwelled in these image-rich places and worked to re-create them in English, so more readers might do the same.

Peñate self-translates her poetry into Spanish, and her three books are printed in both languages. Our project—a collaboration between a linguist, who specializes in and speaks Ch’ol, and a poet who, when she translates, does so from Italian—was, for the first time, to translate Peñate’s poetry from the original Ch’ol. Audibly intriguing, the language’s soft m’s and ñ’s are punctuated by staccatos of k’, ch’, and ts’. It is impossible to replicate the sounds of Peñate’s poetry in English (or in Spanish), and yet we thought it possible to convey in English the lush imagery; tensions of history and modernity, Mayan and Mexican; and near prayer-like feeling of many of her poems.

Translation in any language is, of course, never a matter of simple word replacement, but, in this case, a comparable conceptual framework didn’t exist. In contrast to English, a Ch’ol word may be made up of many small parts or morphemes. For example, in “I Am the Alphabet,” the single word säkjamtyäleloñ can be broken down as säk, bright; jam, open; tyälel, indicating a process (usually marked with -ing in English); and oñ, first-person subject. The literal translation of the word is “I am the bright opening” and, in the context of the poem, “bright light of morning.”

In the Ch’ol language, a word may indicate emphasis because of additions to its root, such as ñäch’äkña in “When I Wake,” literally, “It is quiet.” The root ñäch’, “quiet,” morphs to an adjective by repeating the vowel ä and adding kña and points to an intensification that we built on in the poem. Ñäch’ appears again as ñäch’tyälel. The suffix, tyälel, animates the root word to convey a state of quiet. Our translation, “I hear nothing,” may seem a radical shift and yet not in the poem as a whole.

Frames of reference differ depending on cultural context, and our hope is that, in the translation of Peñate’s poetry, some of these are exposed and considered. In a series of poems about migrants, which includes “When I Wake,” we could not help but be aware that Peñate writes from the perspective of an Indigenous woman in southern Mexico, and that our views are shaped by our own geographies and citizenry. But riding the waves of Peñate’s shifting voice, we found ourselves suddenly gifted with a sort of kaleidoscopic vision, in which imagined experiences included those of the one writing, the one reading, and the one traveling north.

Editorial note: Read translations of three of Peñate’s poems from this same issue.