Landmarks and Mines

There are maps of “Points of Interest” or landmarks tourists visit every summer dotted across the prairies of Sioux country. Landmarks on maps detail where Custer “won” a battle or the site where Laura Ingalls Wilder’s sod home sat. Well-worn tracks of covered wagons are preserved reminders of foreign people crisscrossing our lands. The Massacre at Wounded Knee has a sign neatly condensing an American horror into a few paragraphs where people smile and take photos in front of it, wildly unaware or unwilling to take in the gravity of history repeating itself in perpetuity. To us, the sites are more like land mines. Rife with pain and sorrow, anger, and chaos, each lies in wait, ready to cause destruction and trauma generation after generation, without remorse. If I were to make a Kerouac-esque butcher-paper scroll or map of landmarks and -mines, sans the long-fabled recreational substances, these would be mine, the -marks and -mines of my mother and hers before her.

The 1950s Korean conflict and the 1960s and ’70s Vietnam War’s ramifications echoed World War II holding hostage generations of psychologically damaged soldiers, families, and society, in general. Here are two land mines. The effects of the challenges of gender roles and expectations and race relations carried on in new iterations in a postwar America.

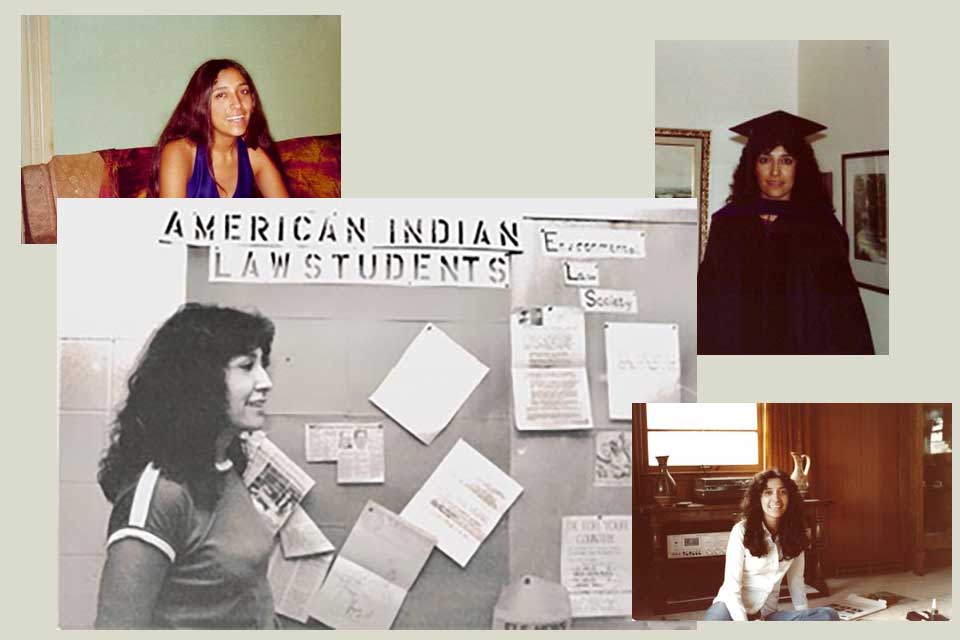

In the US, Native Americans are a minuscule proportion of the overall population yet are one of the highest concentrations of minorities within the military. On top of service, many Native families were systematically separated, moved to unfamiliar urban settings, or boarding schools. Without those bonds, each separation distorted who we were and who we became. During the same era, a substantial number of women, of all backgrounds, became educated and business savvy while soldiers were away. From World War II in the 1930s and 1940s, young couples became parents. Baby Boomers, who birthed Gen Y, Millennials, and Gen Z, each carried a distorted version of roles and expectations to the next. Hanoi Jane aka Jane Fonda received massive backlash for her views against the Vietnam War, negative environmental effects, and promoting women and minority issues; she paid for her commentary in the years following. My mother, Diane Zephier, fought her own battle for equality. Her own Desolation Peak. A -mark and -mine all in one.

Two years after the official end of the Vietnam War, it was 1975 and a striking young woman sat down with her boss, the dean of Arts and Sciences at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion campus. She wanted her salary and benefits to reflect her education and experience in the same way that her colleagues were measured. Her sharp mind and quick wit were rarely acknowledged ahead of her model-like features. Tall, unblemished, golden-brown skin, a mane of long, dark, pin-straight hair cascaded over her shoulder in a chic cut, and a perfect smile distracted from the firecracker within. “After you’re forty, your words will hold more weight than the way you look. It’s just the way it is,” a fact my mother often reminds me.

Her boss quietly sat behind his desk. “I want you to know, it wasn’t intentional. My hands were tied.”

After an injustice is righted, it is impossible to go back to the earlier work relationship. Just as in gambling, the house always wins; when it doesn’t, there’s hell to pay.

You see, my mother, Diane Zephier, was in her first job after finishing her master’s program in social work at USD. She worked with a new, rather WASP-y male colleague, an undergraduate, with less experience. His salary and benefits were significantly greater than hers. Always one to discuss a work-related issue professionally, she met with the dean to remedy the disparity and was at once rebuffed. Though he had negotiated both their salaries, he claimed to be powerless.

Following a consult with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), she was trial-ready, but the dean and university submitted before word of their transgressions spread further across campus. Until then, they had held on to the usual false naïveté and chain-of-command refrain we still hear today.

That day was different. A young woman, a force to be reckoned with, won. For once, a woman won. A woman of color won. Cash in hand, she bought a pretty sports car and drove off to Wisconsin. To law school. Another mark along the way.

The lesson she’d learned was an important one she passed on to me. It doesn’t matter if you have the glory or the name recognition, it is the justice that extends out to others stuck in the same position in the future. It was an era of change in America. Women found their voices both professionally and socially. Though the names in the papers like Banks, Pelletier, and Trudell were well known and brought Native issues to light, her refrain remained: “Any step we can make forward must be attempted.”

It is a thought I keep with me. My mother’s tenacity and drive may not be as well documented as others. She doesn’t want it that way. She is humble and hardworking in the background of so many issues that affect Natives today and in the future. Her work spans actual landmines—the US military’s use of the Badlands as their bombing range, FEMA aid when tornados hit Oglala, and helping veterans who need VA care for an array of issues. These are her landmarks. Most aren’t physical spaces to plant flags but in people who need them now and in the future.

I like to remind her of the time she took on the US government and won. It’s one she doesn’t see as a big deal. She’s humble. Annoyingly so.

Rapid City, South Dakota

Author note: I would like to thank my mother, Diane, who gives me strength, support, and unending patience, as well as World Literature Today, Daniel Simon, and Allison Hedge Coke for including my work among so many great writers and artists.