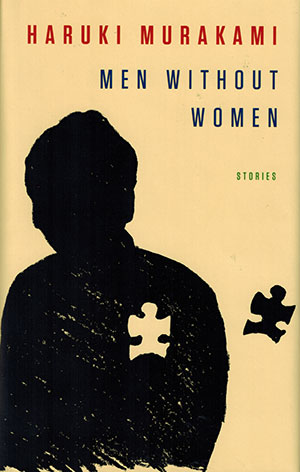

Men without Women by Haruki Murakami

New York. Knopf. 2017. 227 pages.

New York. Knopf. 2017. 227 pages.

Men without Women comprises seven short stories, four of which have appeared in other publications. All display elements of Haruki Murakami’s fiction that readers have come to expect: magical realism, the Beatles, cats and jazz, and abrupt endings without easy resolution. We come to realize this last element is entirely appropriate precisely because there is no pat answer, no comfortable place, no way to tie up loose ends for the protagonists of these tales who, as the title notes, are missing an important woman. The parameters of this lack differ, of course, and the degree to which we can sympathize will likewise vary, but the emotional complications of that lack are something most readers will understand and appreciate at a visceral level, even if the tale seems beyond comfortable comprehension.

Three of the stories are particularly effective. “Samsa in Love” is a playful reversal of Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.” Here, Gregor the cockroach wakes up to find he is human, and his first interaction is with a hunchbacked woman who is convinced he is slow and only interested in her for kinky sex. Like Gregor, we know nothing but the realities of the moment. “Scheherazade” is the most unsettling work in the collection. Here, Murakami is at his best, probing the seemingly unfathomable reasons for connection while asking of the reader a degree of indulgence and understanding of what it means to be needy and the lengths one might go to satisfy those desires. Finally, “Kino” raises far more narrative questions than it answers before sinking almost languidly into a surrealistic pool of self-questioning that also appears to offer an answer only to pull it away at the last moment. This instability powerfully conveys the force of the protagonist’s loss.

Despite the generally engaging nature of these seven vignettes, however, it was with some disappointment that I put the book down, for I could not help feeling that Murakami had been unable to go beyond his previous work. The specific contexts are new, and a different problem is the focus, but the stories feel overly familiar, as if we have read them before. Die-hard Murakami fans will welcome them, and readers new to Murakami will discover why he is internationally renowned. Those hoping for something truly fresh may very well experience a sense of emptiness . . . as do the men without women.

Erik R. Lofgren

Bucknell University