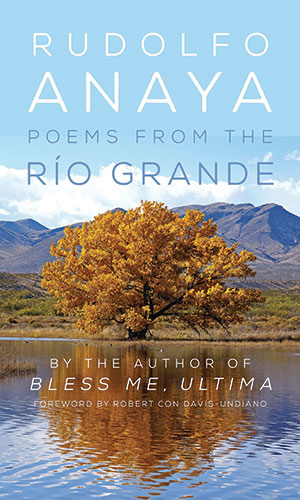

Poems from the Río Grande by Rudolfo Anaya

Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 2015. 103 pages.

Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 2015. 103 pages.

There is nothing like it in Chicano literature. Rudolfo Anaya’s writing, distinct and unusual since the publication of Bless Me, Última (1972), has been an exalted reflection on his regional history and its layered settlements and conflict-ridden peoples: Native American, Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American. Poems from the Río Grande is the first collection of poems by a revered Chicano writer who writes for la gente (the people) but who has also been acclaimed by literary critics around the world for his lyrical prose. In compelling stories, Anaya’s characters achieve fleeting moments of peace and spiritual unity in a land historically fecund with sporadic strife ignited by men hurled from distant shores by hubris and the spirit of conquest.

In the book’s preface (“Poetry as ritual”), Anaya comments on his poetics and lifelong artistic attempts to transport himself to an Absolute from his everyday world, taking him—as a Nuevomexicano—to a heritage woven with threads from different world cultures (“Poetry unites. Poetry connects,” Anaya affirms). Words such as “sacred,” “soul,” and “the Absolute” appear in Anaya’s preface and poems as tacit challenges for the reader to rethink and reconceptualize—from one’s secularized and unbelieving vantage point—the possibilities and experiences latent in a language of transcendence we have all but forgotten.

Originally titled “Songs of the Río Grande” and written over more than two decades, the collected twenty-eight poems stream like the days of a lunar cycle, fateful and varying in themes and moods from a wistful meditation on the poet’s epitaph (“Last Wish”) and a humorous but cautionary fable against drugs (“Beware the ChupaCabra”) to travels with his late wife, Patricia. Other poems refer to legends, myths, and poetic traditions from Egypt, Japan, and Mesoamerica; one poem is a parody of Western classics (Virgil’s Aeneid), sung with Nuevomexicano humor; another in particular, “Elegy on the Death of César Chávez,” mourns the death of the Chicano union organizer. The poems also allude to one of Anaya’s early novels, Tortuga (1979), in which the eponymous main character inherits Crispín’s guitar and accepts from Salomόn his destiny as a guitarrero, a singer of corridos (ballads).

As the elderly version of Tortuga, Anaya strums and sings about righteous heroes, village storytellers, communal food, and the flow of water in fragrant orchards. These poems portray a world that young Mexican Americans, for the most part, have not seen, known, or tasted. Cultural identity and a sense of self can never be the result of a willful confinement, nor of a break from one’s past and a frontier’s new beginning, Anaya seems to say. Poems from the Río Grande consists of poetry that sings of an other America, one that instead of seeking safety in isolation discovers in all rivers of the world—the Nile, the Ganges, the Río Grande—the natural setting for the rise and innovative vitality of a civilization. Mexican American cultural history surges and whirls underground in Anaya’s poetry and narrative, and it is to this all-encompassing river that one must periodically return to drink.

Roberto Cantú

California State University, Los Angeles