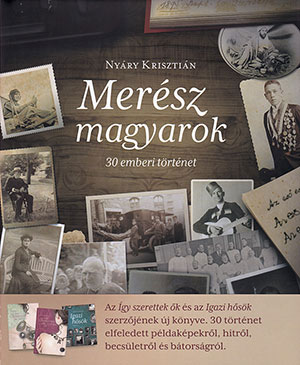

Merész magyarok, 30 emberi történet by Krisztián Nyáry

Budapest. Corvina. 2015. 278 pages.

Budapest. Corvina. 2015. 278 pages.

Merész magyarok (Bold Hungarians) is Krisztián Nyáry’s second collection of sketches and short essays within two years. It follows the very succesful Igazi hősök (True heroes) published a year earlier, and its broad theme is “boldness,” which means pioneering in one field and/or achieving something unusual in another. That includes industrialists, sportsmen, inventors, and soldiers, with the odd writer or artist thrown in for good measure. Nyáry’s time scale is also wide: he wants to save from oblivion both nineteenth- and twentieth-century personalities. The result is thirty “vignettes” of men and women, from all walks of life, some of them truly new discoveries.

The great variety of characters presented in this collection is both the virtue and perhaps the weakness of the book. While it contains elements of surprise and is full of otherwise hidden information, Igazi hősök is heterogeneous and rather eclectic. On its pages one encounters individuals fighting against great odds, becoming examples of determination and endurance. For example, the orientalist Ármin Vámbéry, a lame Jewish Hungarian scholar, feted in Victorian England, possessing unusual language skills (apparently he spoke sixteen of them) who traveled in many Asian countries dressed as a Turkish beggar—in countries earlier “closed” for most Western observers. Or one could mention the formidable twentieth-century heroine Sára Karig, who saved persecuted Jews during the German occupation of Hungary and reemerged as a staunch critic of Communist electoral manipulations in 1947, for which she paid with years of hard labor in the gulag.

Among the brave Hungarians of the twentieth century, Nyáry lists priests and ministers who defied the racial laws of the wartime years, among whom special place should be allotted to Áron Márton, a Catholic Transylvanian bishop who fought both Nazis and Communists. Others in this category include the army officer Imre Reviczky, the nun Sára Salkaházi, and the Protestant theologian Géza Soos, whose flight to the Allies in Italy in 1944 is rarely mentioned by historians. Thanks to Nyáry we learn the name of a priest who—similar to Bishop Péter Apor—died at the end of World War II for resisting marauding Soviet soldiers (Kornél Hummel) and remember the only person who in 1951 managed to escape from the notorious labor camp of Recsk (Gyula Michnay).

Of the thirty stories, eight have brave heroines. Among them Nyáry presents Rózsa Bédy-Schwimmer, the first woman pilot in Hungary, also a leader of the European movement of suffragettes who ended her life in the United States, though without American citizenship. As for its presentation, the book is more of an album than just an anthology, with excellent photographs and illustrations. In the appendix, a brief bibliography broadens the mind of those readers who wish to know more about these men and women of the past whose names are well worth remembering.

George Gömöri

London