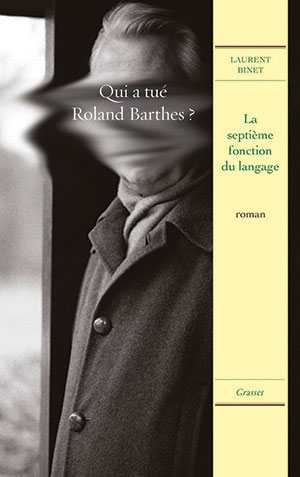

La septième fonction du langage by Laurent Binet

Paris. Grasset. 2015. 494 pages.

Paris. Grasset. 2015. 494 pages.

In 2010 Laurent Binet published a very promising first novel, HHhH, which recounted the 1942 assassination of Nazi general Reinhard Heydrich by Czech resistance fighters. While Binet’s new novel is very different in terms of content and tone, it also reflects the author’s preoccupation with the interaction between narrative fiction and historical events. A learned exercise in satire, the “Seventh Function of Language” turns Roland Barthes’s accidental death in 1980 into a mind-boggling murder investigation that uncovers a vast conspiracy, set against the backdrop of Parisian literary life, during the heyday of what came to be known in the United States as “French Theory.”

Since the seasoned detective assigned to the case is less than familiar with postmodernist jargon, he recruits a young professor to guide him through a maze of literary as well as investigative riddles. In the course of their investigation (which is overseen by the highest levels of the French government), the cynical middle-aged cop and the hesitant young researcher encounter a long list of (in)famous characters, such as Louis Althusser, Hélène Cixous, Gilles Deleuze, Umberto Eco, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, Jacques Lacan, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Philippe Sollers, Tzvetan Todorov, and Roman Jakobson (whose “six communication functions” provide the motive for murder and the basis for the novel’s title). It seems that whoever has access to the mysterious seventh function can wield power over others and potentially change the course of history—hence the utter ruthlessness of intelligence agencies from France and abroad, vying to obtain the document that unlocks the language function’s secret.

Binet sends his investigators to Italy, where they barely escape being blown up in the terrorist bombing of Central Station at Bologna, and to the United States, where they attend a conference on the “linguistic turn” at Cornell University. Along the way there are not only familiar detective-fiction plot twists (bombs, killer dogs, car chases, deaths by shooting, poison, or strangulation) but also elaborate rhetorical duels, with grisly consequences, staged by a shadowy organization that appears to be run by world-class scholars.

The author manages to hold the reader’s interest for nearly five hundred pages by deftly intermingling tantalizing investigative clues and snippets of dialogue among the literary glitterati that are often hilarious and always reflect an in-depth knowledge of each writer’s works. The tone of the satirical portraits ranges from affectionate to pitiless. In particular, the depiction of Sollers’s “histrionic dandyism,” “pathological boasting,” and intellectual vacuity is devastating. However, Binet’s wide-ranging cast of characters is diverse enough to deliver pith as well as mirth. Overall, this quest for the putative seventh function of language is as intellectually sophisticated as it is humorous.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University