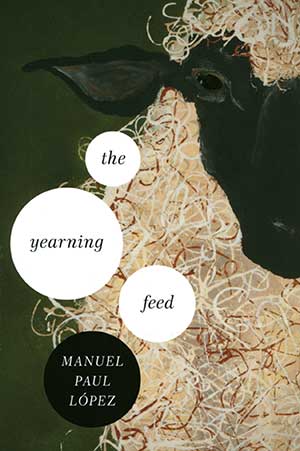

The Yearning Feed by Manuel Paul López

Notre Dame, Indiana. University of Notre Dame Press. 2013. ISBN 9780268033897

It is said that poets are the most sensitive human beings, which may explain the looming cloud of suffering and chaos in The Yearning Feed. It is enthralling and frightening to live in this book of poems: wisdom is so often derived from experience, and Manuel Paul López ladles out wisdom as if from a bottomless well.

It is said that poets are the most sensitive human beings, which may explain the looming cloud of suffering and chaos in The Yearning Feed. It is enthralling and frightening to live in this book of poems: wisdom is so often derived from experience, and Manuel Paul López ladles out wisdom as if from a bottomless well.

Even the cover art entrances and transports one to López’s unpredictable borderland, a close-up of a sheep with wiry white- and-brown wool and endless black eyes. Like Imperial Valley—the borderland where López’s poems originate—he saturates the pages with a sense of in-betweeness; however, the conversational tone and the fragmented verse are all a part of the rhythm of instability on the border.

López invites readers to be split in two: the United States and Mexico. Some readers may feel inexperienced on this subject, but López’s poems invite the reader to experience such duality. For example, in “The Desert Series,” discontentment is felt everywhere and is partially a side effect of the heat in the Imperial Valley. These poems are not only about the heat that the Imperial Valley residents labor under in order to survive but also how the heat is felt on the other side of the border. In “Banter Is All We Needed,” the speaker and friends hear that the “Border Patrol found the bodies of a young man and woman lying down locked in an eternal embrace.” These moments in the poems are quiet ones; they induce prayers, grief for strangers, and sometimes shame that “everything we had already thanked our god for” is not enough.

The struggle for survival that drives these poems comes from the treatment of Latino Americans and Latino immigrants. López’s poems reveal how US citizens distance themselves from Latin American issues yet prefer to consume their labor and goods. Spanning forty-five pages, the poems are undoubtedly López’s most profound artistic statement on the need for human-to-human relations among all the peoples on the continent of the Americas.

In his last, wistful series, “1984,” López riffs Joe Brainard’s I Remember in an astounding style that covers difficult memories in clouds of childlike nostalgia. Balancing the work, the poems in this series impress a sense of hope in light of the contentious race relations between Americans and Latinos—a hope that comes from a child, an ex-junkie, and an immigrant whose safe passage is celebrated because of all those who were not met at the border with open arms.

Marilyse Figueroa

University of Oklahoma