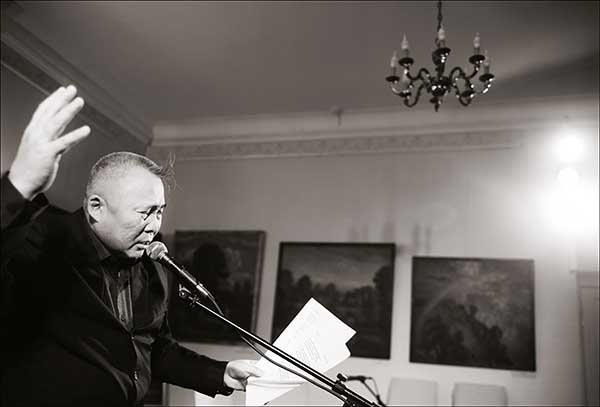

Two Poems by Amarsana Ulzytuev

Listen to videotaped recordings of both Russian originals in the following clip (4:00-10:05).

Shenhen Buryat

Out of the embittering mountains, out of faraway valleys, out of China,

Legends from “under the counter,” the hiding places, Open Sesames,

As though out of the blue the gold hoard of Kolchak’s army

Surfaced, transmitters of forgotten words, bearers of legends and fables.

Untouched by collectivization, like the Lykov family preserve,

They live and toil like an illustration out of a Buryat folktale,

Homespun-plain peasant robes, silken broad cloth-belts,

Conical points of sharp-hats topped with blood-red tassels,

Their horse-tying poles are as high as the mountains,

The hooves of their horses broader than shovel spades,

Blinding smiles out of the malachite casket of the genome,

Speak as the common people do but seem to be singing.

Before the revolution, before fratricidal war, beloved,

Remembering their ancestry to the seventh dislocated generation.

Most devout, like the Old Believers, nomads,

Exiled by the Soviet grandfather frost of the twenties. . . .

Having preserved the old Mongol vertical style script

They carry the steppe’s millennia in their souls

And so sing and love their birthplace by Lake Baikal

And in such a way that we have, probably, long ago forgotten.

Familial

The longest village street on the planet, 17km long,

is in the village of Bichura, Buryat Republic.

– Guinness Book of World Records

Whose are they, the longest village streets in the world,

Washed clean – down to the carved window staves – whose log houses?

Women’s blouses more colorful than the tsar’s own tents, horned headdresses

All done up in amber, still around from the old trade routes, from the Baltic shores.

Their menfolk neither drink nor smoke, but instead sow and till methodically,

Their fists tight around horse-drawn Polish ploughs, and Buryat horsewhips,

Digging up furrows – across the taiga, the hills – Mikula-frontiersmen out of a

fairy tale,

Wear beards – in hut hovels and hamlets – priests-Avvakums of the exiled.

With a saintly expression they arrived here clutching in hand the springs of their faith,

As though falling to their knees to imbibe from them, crossing themselves with

two fingers,

Settling on the edge of the Buryat wilderness at the foothills of the

Beyond-the-Baykal peaks,

As though Ancient Rus’ grown tired of the world gathers up here the

sacred-mountain strength.

From the Buryat learned to eat local dumplings, in return taught them to

make borscht’,

They even speak Buryat – tala, that is friend – all the time singing the old-timey songs,

On occasion intermarried with Buryat women, took local young men for grooms,

That may be why my round-faced grandma’s eyes are a color not from these parts. . . .

What character these provinces that served as place of exile to both the Tsars

and Khans,

Whether it be rotten for the Siberian frosts, or beautiful for its freedom and liberty?

One thing only remains to be done, like a Siberian cedar standing through

rapacious frosts,

To persevere and to pray – Om, Mani! Oh, Thy name, may it be a shining light!

Translations from the Russian

By Alex Cigale