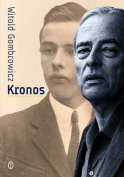

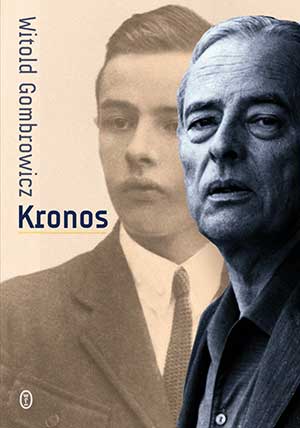

Kronos by Witold Gombrowicz

Witold Gombrowicz. Kronos. Kraków. Wydawnictwo Literackie. 2013 ISBN 9788308050781

In the view of most critics, Dzienniki (Diaries) is among the best writings of Witold Gombrowicz (1904–1969). These are highly stylized diaries that present an egocentric writer for whom independence and authenticity are the highest values. Gombrowicz is a writer who pretends to ignore history, discarding any allegiance to the humanistic or patriotic ideals upheld by many of his illustrious fellow writers. While Dzienniki entails his thoughts for public consumption, the recently published Kronos is in fact a collection of personal notes stretching from 1922 to May 1969, a few months before Gombrowicz’s death.

In the view of most critics, Dzienniki (Diaries) is among the best writings of Witold Gombrowicz (1904–1969). These are highly stylized diaries that present an egocentric writer for whom independence and authenticity are the highest values. Gombrowicz is a writer who pretends to ignore history, discarding any allegiance to the humanistic or patriotic ideals upheld by many of his illustrious fellow writers. While Dzienniki entails his thoughts for public consumption, the recently published Kronos is in fact a collection of personal notes stretching from 1922 to May 1969, a few months before Gombrowicz’s death.

In other words, Kronos provides a sketchy biographical background to the private Gombrowicz. In contrast to the elaborate and often elegant prose of the “Diaries,” it is in a “factual shorthand,” the informative value of which varies from year to year. Beginning with 1940, each year ends with a kind of “summary” of the author’s literary achievements, state of finances, general health, and sexual life. These are not harmonized; for example, during the first years in Argentina (where Gombrowicz arrived in the summer of 1939 on a Polish ocean liner), he has many homoerotic experiences while living in abject poverty; witness an entry from 1943: ”I have no overcoat. I am sleeping on the floor at Morón.” There are months when the writer ekes out a living just playing chess for money (he is an excellent chess player, managing to win several prizes). In later years, his financial situation greatly improves, but then his health becomes an everyday concern.

From Kronos it becomes clear that while Gombrowicz loathed Polish nationalism and eschewed patriotism, what saved him from destitution in Buenos Aires was his job at Banco Polaco, obtained in mid–1947. For the growth of his literary reputation, contact with the émigré journal Kultura and its legendary editor Jerzy Giedroyc was decisive. Finally, when in 1963, thanks to a grant from the Ford Foundation, Gombrowicz left South America for Paris and Berlin and became a writer appreciated all over Europe, he acquired the means to settle in Vence, in southern France. But the notes in Kronos make it clear that in the last five years of his life Gombrowicz struggled just to stay alive: when he had enough money to live in style and married a much younger French Canadian woman, he also had to prepare for slowly approaching death.

Kronos is illuminating in another respect, too. As Jerzy Jarzębski points out in his afterword, Gombrowicz’s notes make it clear that those critics who declared him “completely gay” were wrong. Gombrowicz was bisexual, and in the Polish half of his life females dominated as casual sexual partners, though mainly in the form of prostitutes and serving maids. In the Argentinian section, there are many more chicos than chicas (Gombrowicz often uses Spanish words in these diaries), but in Vence there is again a return to “straight” sex thanks to Rita, whom he finally marries. Kronos also reveals the secret that Witold Gombrowicz was treated through many years for venereal disease, though it was not eventually the cause of his death. He also had a number of women friends devoted to his charm and talent, some of whom (like “Litka,” i.e., Alicja de Barcza) even supported him financially.

Kronos sheds light on the tensions between a writer’s everyday life and his literary achievement. It is not an easy read but is full of relevant information for the literary historian or for special fans of Gombrowicz. The text is accompanied by a large number of photographs, many of them from the archives of Rita Gombrowicz.

George Gömöri

London