Soccer, Art, and Desire

An interloper in a male world, Yrsa Roca Fannberg in her Barcelona FC watercolors paints the "ordinary gestures" that the experts often ignore.

Yrsa Roca Fannberg's quixotic blog, art versus sport (artversussport.blogspot.com), is what the title promises, a site pulled in these opposite directions. Art seems to be winning the battle: in recent years, Fannberg's entries tracking the emotional highs and lows of a Barcelona fan have thinned.

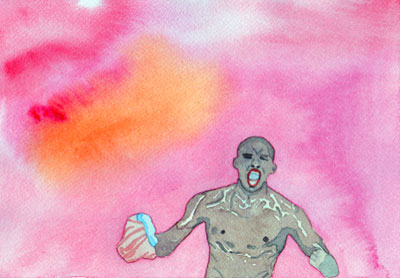

Fannberg is a documentary filmmaker and photographer—the center of her practice is the camera. She makes these gorgeous watercolors on the side, painting them in the same thoughtful spirit with which she writes—with a feel for mood, posing delicate questions of psychology and emotion, with an eye trained not only on the sublimity of the sport but on the melancholy beauty of its more ordinary gestures.

Since I became obsessed with soccer, people around me have struggled for points of entry into conversation. It is hard for me to feign interest in anything else. It's a special form of belligerence, in which you are so single-minded, so actively engaged with one topic, and so utterly passive around all others that you drag out of your interlocutor whatever they know about this one thing. This is how I learned about Fannberg's work. I was at the opening for an art show, standing against a wall holding a glass of wine and a copy of Jude the Obscure. A nice man and woman tried talking to me. Casting around for any intersection between our lines of interest, the woman (the artist Georgina Star) remembered that there had been a woman in a class she taught once who was also obsessed with soccer. She wrote her e-mail address into my copy of Jude and, after a brief exchange, she sent me Fannberg's name and a link to her blog. It wasn't long before I went to Barcelona to meet the Barça fan.

It was a joy to meet a woman similarly engaged by the sport—for those of us whose identities are primarily bound up in art and intellectual life, an absorbing passion in soccer can be quite isolating. Even though many women play and become fans, our affection for a sport that men all over the world feel is "theirs" makes us interlopers. (FC Barcelona is only now making overtures to its numerous women fans, and one might safely say that this late gesture is well in advance of most European clubs.)

Speaking for myself, when I have tried to talk soccer with men as a way to, well, talk to them, I have come away with the distinct impression that I have violated some major rule of womanly conduct. For example: one Saturday afternoon, I sat on a London-bound train with my friend Mandy Merck, an ardent (and intensely critical) Arsenal fan. She has followed the team since god knows when and is no casual expert on this subject. Arsenal had just played—and lost—a critical midseason match. It was that perennial winter game Arsenal loses in order to quash illusions built on a promising fall run.

Across the aisle were two men: a BBC sports journalist and an American tourist. They were talking football and stuck with this subject for a full two hours. They talked about relegation: a fascinating, exotic form of sport brutality for us Yanks. Relegation in soccer is the demotion of bottom-finishers at the end of a season to a lower division; it presents a crisis for club owners, who must cut expenses in anticipation of lost revenue. As it happens, I had just read National Pastime, a comparative economic analysis of major-league sports in the United States and around the world, focused in part on the relegation system and its economics. I mentioned this in a casual, conversational way. The two men (whom I had interrupted) looked at me, said nothing, and then continued talking as if I had said nothing.

Of course, this is not the best example to prove my point. Trying to enter any sports conversation by talking about an academic textbook is probably not the best idea. My relationship to the subject of sports is hopelessly dorky. My friend had not even bothered trying to talk with those guys. Why would she? She knows far more about the game than they do. She welcomed me back to our discussion with a knowing look. It sucks to be shut out of a conversation because you are a "girl"—and that sense of rejection is made worse when a guy looks at you like you are stupid. But who needs to talk to men about these things anyway?

When men talk soccer with each other—when they talk in great depth and with enormous intensity of feeling about other men—those conversations are often not really about soccer, but about their relationships to each other. It is a socially sanctioned form of conversation between men, the last arena in which they can pretend women do not exist. Women who try to take part in this sort of talk upset the delicate balance of tenderness and disavowal that allows guys to talk with and about guys without, well, thinking about guys.

Fannberg's work allows us to see what is right in front of our faces, but which sports media disavow. Most representations of soccer players are hyperheroic, hypermasculine. When she offers a visual meditation on that ecstatic postgoal moment, she literalizes this explosive joy as men coming apart in each other's arms. Sports photography tends to amplify the testosterone even in failure, when our sports heroes are made to look like fallen soldiers. Not often do we see them look like the big babies they sometimes are, on their bellies, fists pounding the grass.

A portrait of Thierry Henry makes the player look like he is weighed down by his own feet. If you have ever played ninety minutes, you might relate—I know that there are times when the ground feels attached to my shoes—like the earth itself is grabbing me by the ankles.

Fannberg's images are quite plainly made out of love. And that love is not filtered by the requirements of the macho/heroic tradition that sifts out and decides on its own sentimentality. It would be reductive to say that the artist's gender gives her permission to approach Barça with this kind of delicacy of feeling. She played in Sweden until she was fourteen (she says she was terrible), she is half-Icelandic and half-Catalan, she is an artist looking at sport. She approaches the subject of Barça and football culture with the insight of an insider and the perspective of an outsider.

When we met in Barcelona, she took me to a bar and spread her portfolio out on our table. The waiters stopped, called others over, and pointed to the portraits: "Oh, that's Messi, for sure, look at how he holds his head," and "You can't miss Thuram there." They shook their heads in maternal consternation as they identified the prodigal son and sighed, "Ronaldinho." Our faces lit up with a kind of warmth—the same warmth that animates Yrsa Roca Fannberg's images: these are members of the family, and we love them no matter what.

University of California, Riverside