Olivia Elias: The Rooting of the Poem

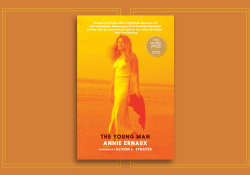

Olivia Elias’s singular voice has not gone unnoticed in the Palestinian poetic landscape. A French-speaking poet and child of the Nakba, her work, published only since 2015, has already been picked up by numerous magazines and translated into several languages. Chaos, Crossing (World Poetry Books, 2022), the bilingual, expanded edition of her latest collection translated into English by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, offers a glimpse of the blend of anger and tenderness that forms the bedrock of her poetic universe: an exercise in poetic rootedness that transcends her condition as a Palestinian exile to invent a language capable of expressing, on a universal scale, the duty of indignation and solidarity.

Olivia Elias’s singular voice has not gone unnoticed in the Palestinian poetic landscape. A French-speaking poet and child of the Nakba, her work, published only since 2015, has already been picked up by numerous magazines and translated into several languages. Chaos, Crossing (World Poetry Books, 2022), the bilingual, expanded edition of her latest collection translated into English by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, offers a glimpse of the blend of anger and tenderness that forms the bedrock of her poetic universe: an exercise in poetic rootedness that transcends her condition as a Palestinian exile to invent a language capable of expressing, on a universal scale, the duty of indignation and solidarity.

Born in Haifa in 1944, Olivia Elias and her family fled to Lebanon in 1948. After studying economics and a teaching career in Montreal, a city she discovered at the age of sixteen, she moved to France in the 1980s. Her first collection, L’espoir pour seule protection (Hope as only protection), was published by Alfabarre in 2015, followed by Ton nom de Palestine (Al Manar, 2017), translated by Sarah Riggs and Jérémy Victor Robert as Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023), and Chaos, traversée (La Feuille de thé, 2019).

In his foreword to Chaos, Crossing, Palestinian poet Najwan Darwish describes Elias as “one of the most unexpected voices to emerge from Palestinian poetry over the past decade.” For Darwish, Elias’s relatively recent arrival on the Palestinian poetic scene is the culmination of a personal journey marked by the experience of a double exile, geographical and linguistic. Elias’s poetry is “personal yet collective, simple yet complex,” and “always astonishing.”

As with other Palestinian poets, questioning predominates in this collection. But here, more than anywhere else, the questions speak forcefully and painfully of the need to share the anguish that is at the root of being Palestinian: “Do you know the sound of an olive tree being uprooted?” or “How to solve the equation of maturing in the country of the absentees and the present-absentees a country that plays hide-and-seek with existence?” For Elias, the question doesn’t necessarily call for an answer; it’s there to hammer home a burning reality, to force the reader to look the Palestinian drama in the face.

From one poem to the next, Elias sketches the contours of a precarious Palestine, caught in “the circle of hell,” constantly struggling against the instability and fragility of its existence: “In this country, the stars were not fixed.” Some poems condense the despoiling of Palestinian land into starkly realistic images, such as “the mortal embrace of the yellow bulldozers” or “the swelling of the earth’s skin.” The continuing reality of colonization in the Palestinian territories results in an “extension of the territory of banishment.” The Nakba, Elias reminds us, is still ongoing.

The continuing reality of colonization in the Palestinian territories results in an “extension of the territory of banishment.” The Nakba, Elias reminds us, is still ongoing.

In a poem written in 2018 that resonates strongly with the painful current events in Gaza, Elias pays tribute to the “hundreds and hundreds of / thousands of imprisoned shadows” and asks premonitory questions: “how long must those in Gaza wait for the Devastation to be named? / how long must we keep the journal of grief and affliction?” It is from this feeling of powerlessness that a Palestinian temporality is woven, dominated by waiting and the absence of perspective.

From then on, the poem becomes the place to evoke the house, the olive tree, or the field that has been despoiled, with the feeling of a profound injustice that goes so far back in time as to alter the sacred place of childhood: “from the tales of my childhood only / the ogres have been reborn / busy elsewhere the fairies / watch over other cradles.” Faced with the reality of “amassed precarity,” the exiled poet is forced to carry her home on her back like a “snail shell.”

In this landscape marked by uprooting and instability, a few pockets of resistance appear in the poem. Here, “the conspiracy of trees / and old stones,” there “the ones who endure / the Refusers / armed with stones and kites.” Elsewhere, a child believes in the existence of a pebble more than his own, and hunger strikers make “the body that devours itself” their “last sacrifice for freedom.” Far from slogans and platitudes, resilience seems to spring from the bowels of the poem, sweetness distilled “drop by gentle / drop despite the bullets / following fault lines.” It is the poem itself, “riddled with shrapnel,” that takes it upon itself to extract “the sniper’s bullets / from its heart.”

Beyond Palestine and its torments, Elias’s poetry, as the translator notes in his afterword, “travels with ease, and sometimes in the same breath, across the whole world,” giving us to read “a poetic chronicle of the uprootedness of our times, times marked by inequality, injustice and disconnection.” Whether evoking the painful separation between an old man and a child in the hell of the Syrian war, or paying tribute to migrants, those “explorers of modern times / survivors of hellish odysseys,” Elias’s voice is always carried by the right blend of realism and empathy.

Here again, poetry is not limited to description; it challenges, questions, engages in dialogue with human spaces and experiences. Addressing the Mediterranean Sea, she observes: “The promise / of the other shore / contained in your name / grows more distant / each day,” then asks: “How could I forget / your oceanic trenches now turned into cemeteries?” On the subject of George Floyd, who died “crushed like vermin,” she asks: “Would your death be a sacrifice / the gods demanded to invite / to the banquet table those excluded / from the good life condemned to / die a second time?” By confronting her writing with the violence of the world, Elias underlines the inextricable link between poetic space and lived experience. Sometimes, just a few words are enough to say what’s essential, as in the case of the Covid pandemic: “It was a senseless time / the dead were seated at the table.”

To express the poem’s roots in personal and collective history, Elias’s writing often opts for economy and rhythmic variation. By freeing itself from articles and punctuation, it inscribes a sense of instability into the flesh of the poem: “Walking on cracked ground / that pitches like the deck of a ship.” The tightening of lines often reflects the poet’s anxiety, as when she seeks a way to express her hypothetical return to Palestine: “vocabulary dwindling dwindling / with what to replace words / impossible to pronounce,” or when she attempts to render the fracas of war: “raids lootings olive trees sawed-up / burned operations Cast Lead / Pillars of Defense/ here there.” Laconic and devastated, Elias’s poetry embodies both the accumulation of images and the lightening of structures, openness to meaning and resistance to all forms of enclosure.

A close reading of Elias’s poetry reveals that it is part of a project to reinvent poetic language, “a scientific approach” (the title of one of the poems), as it involves “circumspection,” “rubbing pebble against pebble / of language,” inventing another “sign language” with the material of juxtaposed pain and anger. The result is verse in which a simple image, like that of a crutch, becomes synonymous with the thousands of lives shattered, bodies and territories altered by occupation. In a state of permanent poetic quest, Elias stubbornly seeks ways to strengthen her resistance. In the poem “Mantra,” for example, she wonders whether she should “build a dike / with everything / I can get my hands on / words objects feelings / to recycle.” To counter uprootedness and dispersion, Elias counts on poetic energy, affirming the necessity “to do the work of an archaeologist” and to “rebuild a dwelling open / to tenderness” with “the debris of the present.”

A simple image, like that of a crutch, becomes synonymous with the thousands of lives shattered, bodies and territories altered by occupation.

At times, Elias’s poetry escapes the world’s turmoil and becomes more intimate, almost confidential. The poem then becomes a means of “floating on the surface of oneself,” of meditating on death and the encounter with “creatures / from the world below,” but also of saluting the memory of one’s grandmother, reconnecting with childhood dreams, or dreaming of a salutary reincarnation. Elias’s poetic approach always seems driven by “this cumbersome desire to do well,” by the vital need to remain “immune to defeat & desolation” and to get through trials by seeking, as Abu-Zeid notes, “the still point in the midst of chaos.”

Borrowing quotations or references from Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Baldwin, Beckett, Aragon but also Lao Tseu, Hideo Furukawa, and others, Elias opens her poetry to the world and extends her poetic roots far from her native land—she who signs one poem: “scribe-citizen of occupied Palestine and the world.” In English, Kareem James Abu-Zeid’s limpid, sensitive translation extends the geographical and poetic openness that underpins Elias’s writing and shapes its originality. Another way of putting Palestine and its diaspora back on the world map, if need be.

University of Chicago

Editorial note: This review first appeared in French in the literary magazine En Attendant Nadeau on April 16, 2024. Elias’s poem “Offering” appeared in the “Palestine Voices” issue of WLT (Summer 2021).