Lizards’ Colony

“Everything has a price,” but how do you put a price tag on the human condition? In Mahmoud Saeed’s unflinching story of abjection and brutality, the moral cost of war is calculated on the balance sheet of a single human life.

She opened the door of the trailer, the rising sunlight submerging her. The still air was saturated with extreme humidity, making it feel like Basra, and the temperature was close to ninety-five degrees. The heat might have been tolerable but not the humidity, which left heart, soul, and spirit filled with loathing. Besides, something somewhere was making a stench like rotten eggs—no, decaying fish. Was it the sewers or the rank smell of the sea? Was she imagining it? Was this a result of the shock of the rape that had kept her in the hospital for ten days? Who could say?

During those ten days she had consumed nothing but liquids. How could a person work in a hostile environment with everyone else lying in wait? She was raped and lacerated. She had entered a hospital the first day and had received her work there; no one cared about what had happened to her. Before she had time to heal, a load of documents had been dumped on her head, documents she had to review: dozens of tape recordings for her to hear and reconcile with the huge companion file. She started in the hospital and then finished in the small, cramped, stifling trailer. She read while the pains racking her midsection grew increasingly intense and uninvited tears came to her eyes. She speculated about the appearance of Ahmad, the able-bodied terrorist covered by this huge file and the many tapes. He was no doubt an awe-inspiring, powerful, grand giant with a muscular body. She gazed at the sky. Why did it look pale blue in the morning? Distant white clouds were threatening rain. She wished she hadn’t committed the great folly of accepting employment with them. Had she realized that she would be working in this great prison, which is what exile amounted to, burdened with humiliation? All she could think about was her innocent daughter. What good was remorse? If she had remained at home, the child would have grown up deformed before her eyes while the cancerous globe in her skull increased in size as she grew. She would have become a monster inspiring both fear and sarcasm. She would have suffered her entire life along with the rest of the family. “Everything has a price,” as General David had said. Life was like that; she had just paid the price in advance.

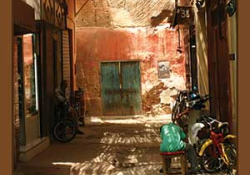

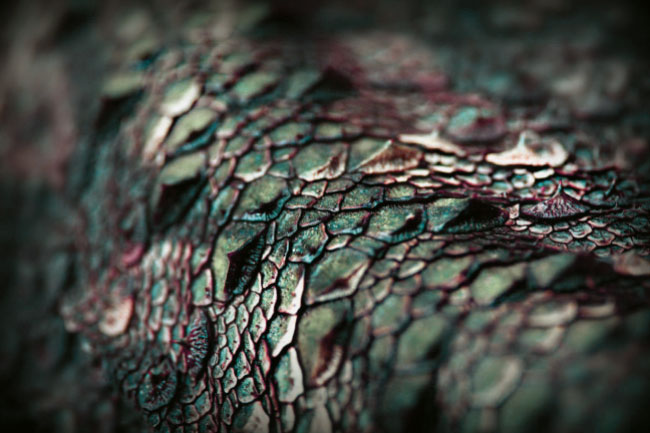

The ground before her was crawling with green lizards with iridescent green spots gleaming on their backs. She had arrived by night and been raped by night and had not seen them before.

A hot breeze rife with humidity and decay stirred; yes, this was the rank smell of the sea, but where was it? She really wished she could glimpse it. She looked north, south, and east but didn’t catch any glimpse of it. All she observed were the numerous watchtowers. These were nearby, awe-inspiring, but others extended to the far horizon, covering a distance she could not estimate, and resembled small, delicate matchsticks.

She smiled. Seagulls appeared in the distance, coming from the east, filling the sky with their mischief. The sea must lie in that direction; there wouldn’t be seagulls without a sea or at least a river. What was this? What a seagull! It was so dark it was almost black. Was everything different in this place of exile from the world? Even seagulls? Was the gull really dark, or did it just seem that way because of her disaster? She stretched as tall as she could, standing on tiptoes, and looked carefully. The sea was visible as a distant, fine, white line off toward the horizon. She reckoned that if she climbed onto the roof of the trailer she would be able to see it, but that was impossible; there weren’t any steps leading to the roof inside or out. She also figured that if she descended the trailer’s three steps she wouldn’t see it and would not even see the horizon. The high wall with its raised military towers shielded the camp from everything beautiful: the sea and its waves, ships, the coconut plantations, and the endless fields of sugarcane. She ought to ask if they would allow her to at least get a look at the sea. What a silly desire! She knew that exploring outside the prison was forbidden and actually a criminal offense punishable by law. She knew from the papers she had signed that the road linking the prison to its surroundings could only be traversed with special permission of the supreme commander. The only access was by helicopter. Anyone who attempted to leave without boarding a helicopter would be shot. Anyone entering by land would be shot. Anyone approaching the fence from inside or outside the camp would be shot too. But she had not read any clause in the contract stipulating that a man who raped a translator would be subject to the death penalty or even prosecuted. What a cruel world—a world filled with injustice—pulverizing its victims.

She looked at the ground for the first time. What was this? She was alarmed. The ground before her was crawling with green lizards with iridescent green spots gleaming on their backs. She had arrived by night and been raped by night and had not seen them before. Their protruding black eyes were still but glowed. Were they dead or asleep? Did they sleep with their eyes open? Or do you suppose they were awake? She was alarmed. No, she wouldn’t set foot on the ground at all. She remained standing at the door of the trailer with Ahmad’s file in one hand and the tapes and a booklet containing hundreds of words of Moroccan dialect, arranged alphabetically, in the other. A telephone call from General David Mueller had awakened her an hour ago. He had ordered her to wait for him. She wouldn’t set foot outdoors until he arrived. From where she stood at the door of her trailer, she began to estimate the number of lizards that transformed the color of the sunburned dirt to green. If there were three lizards in every square meter, how many would there be in ten thousand square meters? Thirty thousand. Wasn’t that right? But how large was the prison? Twenty thousand square meters, thirty, forty! Who knew? Could there be more than a million lizards?

She closed her eyes. She wouldn’t look at these lizards at all. She would look at the sky. They hadn’t said anything in the contract about walking among wild beasts she had never seen before, repulsive creatures like these lizards. “Let’s go.”

Hearing a voice on her left, she turned and saw the general. He called out, “Come.”

She stared at him and the lizards, and her alarm showed clearly on her face. He smiled and yelled, “Come. Don’t be afraid.”

But she stayed put; so he approached and, when he was a meter from her, said reassuringly, “Don’t be afraid of them. They won’t hurt you unless you step on them and give them a chance to bite you. In that event, they’ll leave a mark like a tattoo on your skin, and it will stay with you till you die. This is why we’ve provided you with knee boots.”

He continued, “Come on down.”

She descended the three steps and stood on the ground, looking carefully at where she set her feet. A concrete walkway a meter wide dissected the wasteland before her, leading from a group of trailers clustered behind her to the prisoners’ distant cells that spread throughout the camp before it and ended parallel to the high walls that made it impossible to view the wide sea. Before reaching the walls, it intersected with another concrete walkway that led to another group of trailers situated to the left. If she and the soldiers and officers were quartered in her set of trailers, who lived in those?

Once again she looked down at the earth. The lizards filled the concrete walkways and the court with its grass, which had been browned by the sun and reduced to thorns and yellow stubble. She wondered how she could walk through that.

She looked up dubiously at the general’s blue eyes, and her lips ventured a forced smile that did not last long; her face lapsed back into an apprehensive expression accompanied by a despairing sigh.

To spur her on, General David repeated, “Don’t stop now. Come.”

“You said they bite.”

“Only if you tread on them.”

She didn’t move, so he shouted to hurry her up, “Don’t be afraid. They have a good sense of hearing and run away. Look.”

He took a quick step in front of her, and the lizards started to flee from his footsteps in various directions. They reminded her of the Shatt al-Arab’s minnows that flee quickly in response to any motion in the water—when someone throws a stone or drops a date.

The general turned toward her and urged, “Let’s go. You’re the only one left. When you entered the hospital the night you arrived we had four translators. They were all dispatched elsewhere. There’s more than one hot spot in the world. They needed them after the invasion. Another batch of translators, men and women, will arrive today or tomorrow.”

He began to walk away agilely, and she tried to catch up with him.

Turning back toward her, he asked as he prompted her to walk, “Have you read the file?”

“Yes.”

“How about the tapes?”

“All of them?”

“How will you interview Mahamad al-Marrakishi?”

She realized that he was testing her and replied, “Ahmad al-Maghribi, not Muhammad.”

He smiled and did not say anything. A moment later he turned again. “Have you prepared questions?”

“No, there aren’t any questions.”

“But I told you to.”

“You told me to study the file.”

“Did you study it?”

“Yes.”

“No questions?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure that didn’t inspire any questions?”

“There are some murky matters.”

“Murkiness inspires questions.”

“No.”

He stopped, and she stopped. He looked at her disapprovingly and asked sharply, “What is this contradiction?”

“There’s no contradiction whatsoever.”

“What do you call it?”

“Confusion.”

He walked forward, and she walked behind him. He turned toward her. “I haven’t understood.”

“Are you asking for my opinion?”

“Yes.”

“The reports differ totally from the tapes.”

“How so?”

“In the written reports he is said to have confessed but not to have disclosed his assistants.”

“True; that’s why you must have questions.”

“No.”

She stopped, and he turned toward her. “Don’t stop. Our time is valuable. You can talk while you walk. Explain what you mean.”

“Anyone who listens to his statements on the tapes realizes that he has disclosed everything. There’s nothing else that deserves fresh interrogation.”

When she saw that he wasn’t responding to her, she guessed that he was thinking about her words. He continued walking while she followed him; both of them were silent. Then as if addressing himself, he observed, “No, he didn’t make a clean breast of it.”

“The file says that; the tapes tell a different story.”

“He’s lying. He must tell the truth.”

The general in front of her walked so nimbly that a person looking at him from a distance would think he was in his thirties or forties though he was about sixty-five. Suddenly he turned left. She saw a blond soldier whose skin had been bronzed by the sun. Wearing a clean uniform, he was in his twenties and walked behind her, keeping his distance. Seeing her look toward him, he hurried to catch up. When he drew near, he smiled at her. Their eyes met briefly, and she felt disheartened. She was reminded of the rape that had lacerated her organs and caused her to lose more than twelve pounds in the hospital. She didn’t know why she looked at him a second time. The soldier was smiling broadly. What did that mean? Had he participated in the crime? She wasn’t able to discern anything from his smile. Was he innocent or such a skilled actor that he could flash such a neutral smile? She focused her gaze on the general’s back again and hastened her step to walk beside him. He was slim, of medium height, and the sun had turned his skin as brown as that of any native of the region. When he reached the fork in the concrete walkway, she thought he would head right, toward the prisoners’ cells, which were packed together all the way to the horizon, open to the air, sun, and winds. Instead, he ignored them and headed to the dozens of trailers that were grouped together like a small village about two hundred meters to the left.

With the same agility, he mounted the three steps to trailer number ten and opened the door so forcefully that it groaned from the thrust of his powerful, sudden push. The air in that trailer was hot, humid, and repulsive. It was almost dark. Another soldier, who was stocky and almost bald, had been gazing out the north window of the trailer toward the horizon. He seemed startled by the sudden opening of the door. He sprang to attention, drawing himself erect and fastening his eyes on the general. She entered, following the general. Then the dapper blond soldier was inside the room; he slammed the door behind them with comparable force and a similar bang.

Some seconds later she discovered the prisoner on the bare floor before her and assumed that this was Ahmad al-Maghribi, whose statements she was obliged to translate. The prisoner wore a red jumpsuit composed of two pieces. His two forearms were spread like the Messiah being crucified; one leg was fastened around the naked ankle by a chain with gleaming links that was connected to a large peg in the floor of the trailer; the other leg, from which the foot had been amputated, was covered with a white sock, and the remainder of this leg was fastened by calf and knee to another chain that was connected to a similar peg in the floor of the room. She looked at the ball that presumably was a head but observed no human features on it because a large red bandage extended from the forehead to the nostrils. A second cloth covered the mouth, and a third the ears. The only suggestion of a human being in the body before her was the nostrils, which were only visible to an observer looking directly at them. Was this a man? Perhaps it was a mannequin they had dressed in prison clothes or an inflated blow-up figure made of nylon. If this was a human being, it wasn’t any giant, and he didn’t seem to be the powerful colossus described by the reports. Who could say?

“Zaynab.”

She was amazed that the general had pronounced her name correctly, as if he were an Arab or was proficient in Arabic. Since she had emigrated she had worked as an English-language instructor but had never heard anyone pronounce her name as correctly as General Mueller. This trivial point lightened her rage and pain, and she turned toward him. She remembered the file and the tapes. He must want elucidation of specific points, and that made her feel apprehensive. She had just spent two days in the hospital and most of the day after she was released studying the file, which had driven her mad, made her dizzy, and left her feeling she couldn’t think straight. She had read everything in its more than one hundred pages packed with information and ample details, comprehensive confessions—as Egyptians say, from “Nice to see you” to “Goodbye”—the whole story. At that time, her insides had been totally ravaged by the pains of the rape. She had put white papers in the file at places she expected to provoke questions. Where was the contradiction, then? What need was there for interrogation? She didn’t know. What should she do? She didn’t know!

Her hands trembled suddenly. There wasn’t any ambiguity about the matter, but she had expected that she would ask about some points that the previous interrogators had focused on with extreme stupidity. She closed her eyes to collect her thoughts. Then she opened the file. Where should she begin? She felt bewildered.

The general did not speak to her. He was staring at the stocky soldier, who quickly opened a door on the right and then fetched a rattan chair. The general sat down behind the crown of the prisoner’s head. Then he looked again at Zaynab with concern. The blue of his eyes looked strangely translucent, as if they were pale blue glass that had been surgically implanted in his eyes, two glass globes that penetrated deep inside him. For the first time she noticed some delicate wrinkles and swellings beneath these eyes; these seemed the result of time’s persistent action. When he noticed her gazing at his eyes, he asked, pointing to the prisoner, “Why don’t you go ahead and question him? We could rot here for ten more years without accomplishing anything of importance.”

She didn’t understand what he meant. She was disturbed and fearful as he stared at her impatiently. Meanwhile she noticed a triumphal smile in the eyes of his aide. The general said to prod her, “Double-check the information in the file and the tapes.”

Her hands trembled suddenly. There wasn’t any ambiguity about the matter, but she had expected that she would ask about some points that the previous interrogators had focused on with extreme stupidity. She closed her eyes to collect her thoughts. Then she opened the file. Where should she begin? She felt bewildered. What was this test before a general who considered rape inevitable in this remote place of exile? She had made many notes about the contradictions of the interrogators, their diverse orientations, and the endless disconnects. She could have wept. More than one person had participated in the interrogation. They had asked, examined, employed devious stratagems, and left their scribbling, fingerprints, and folly, Captain John Keller, Lieutenant Welby, Captain Jim Seford—with writing in many colors: red, green, and black—on every page. Words and sentences had been highlighted in various colors, and differences of handwriting and expression were obvious here and there. Every few pages featured a novel handwriting with a new pen. There were diverse comments, but these all converged on one point: that Ahmad Attawil was dangerous, a systematic, profound thinker who devised terrorist plans of the first caliber and an extremely vicious man. There was also a full report from Husayn Jalali, an adjutant close to the betrayed leader Shah Mumdi. Since the general continued to stare at her, she decided to do something. So she squatted close to the left of the prisoner’s head where she could see both the general on one side and the prisoner on the other. Suddenly a fierce fire blazed through her wounds in her midsection, and she was afraid she would start bleeding. She bit her lip and would have liked to ask the soldier to bring her a chair but rejected this idea for fear of getting on the general’s nerves.

Extending a finger toward the prisoner’s bandages that covered his eyes, ears, and mouth, she asked, as her pain could have killed her, in a voice that she meant to sound patently sarcastic, “Can he hear me if I speak to him?”

The general looked up at the stocky soldier, who stared at them. His hands were busy pulling out small microphones that were connected to a large black recording device like nothing she had ever seen. He began to attach the mikes to the prisoner’s chest, the general’s shirt, and Zaynab’s blouse without uttering a word. Then he squatted on the far side of the prisoner’s body and quickly began to loosen the bandages. He began with the earplugs and then removed the gag. A long sigh of relief escaped from the prisoner. His face was handsome and his complexion fair, a milky white. He opened his mouth as if trying out his lips. Then the area around his mouth, which was guarded by a delicate mustache and a coal-black beard a couple of centimeters long, relaxed; she wasn’t sure whether he was smiling or in pain, because the wide band covering his eyes reached from his forehead to his nostrils. What she could see of his features suggested he was in his rebellious twenties; perhaps if she saw his eyes and the rest of his face she would be able to deduce his age. She expected that he was no older than twenty-five in any case. Her heart pounded. She now knew three things more about him besides his name—his complexion, his clearly defined mouth, and the long cleft in his chin—and all of this reminded her of her brother, Ahmad. When she had leafed through the file, she had thought that all they had in common was their name. What further resemblances might there be? Would he have kohl-black eyes like Ahmad’s? She would have liked to see the rest of his face. She would have liked to embrace him.

How many hours would he have spent deprived of existential sensory input—no people, no world? She hesitated before addressing him. Would he be able to hear her? If he heard her, would she be able to awaken his senses so that he would respond serenely? The general’s eyes were fiery lances piercing her eyes, goading her on. She moved her mouth closer to the prisoner’s left ear and said, “Ahmad.”

He turned his head toward her without saying anything. She added, “Please listen to me. They found you heading for the border. Who gave you the explosives? To whom did you intend to deliver them? Why don’t you confess so you can rest in peace?”

The general shouted, “What did you ask him?”

She translated what she had said. He smiled and nodded his head in agreement. “Carry on.”

The prisoner did not reply; she repeated the question.

The prisoner opened his mouth and she smiled. He asked, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

The general asked her, “What did he say?”

She looked up at him. “He used Moroccan words I don’t know. I’ll look them up in the booklet.”

She searched for the booklet among the tapes, and it slipped from her hand. She leaned forward to pick it up, causing a sensation like a sharp knife stabbing her wounds. She groaned in spite of herself.

“Is it Arabic?”

Her voice quavered from pain. “I don’t know.”

“French, then.”

“No.

“Perhaps Berber.”

She didn’t know how to deal with the pains from her wounds or the general’s insistence and almost cried out in distress. Gaining control of herself, she said, “Give me a moment. Let me see.”

The general was obliged to remain silent. The prisoner laughed—to mock him, the general felt. He declared in a voice that was almost a scream, “Do you see what a rogue he is!”

The prisoner laughed again, loudly, and Zaynab deduced that he must know English and that he enjoyed playing with the general’s nerves. She looked at the general and yelled delightedly, a smile covering her face: “I found it. I found the meaning of the words. Lalla means “lady,” dirri means “child.” He asked me, ‘Lady, how many children do you have?’”

The general, still furious, roared, “Tell this motherfucker that we’re the ones asking questions—not him.”

She changed the direction of the questions, asking the general, “In the file there is something about incentives. If he confesses, how will he be compensated?”

“We’ll release him.”

The prisoner guffawed in a profoundly sarcastic way.

“Do you see? He has nerves of steel.”

“Shut up, motherfucker!” the general shouted loudly.

Ahmad, however, continued to repeat melodiously in a low but audible voice, “Oh, Iraqi lady, how many children do you have?”

She commented, “Don’t pay any attention to him. Let him say whatever he wants.”

The general lowered his voice but was still upset. “When the prisoners went on hunger strike, some prisoners broke their fast after a week, others after two weeks, three, or four; he’s the only one who held out for many weeks. He set the record. Who is tougher than him?”

She leaned down toward the prisoner again and asked in a calm voice that she hoped sounded affectionate, “Ahmad, what would you lose if you confessed? You have everything to gain: freedom, relaxation, and happiness.”

This time the general didn’t ask her to translate her question orally but gestured for her to write it down. So she wrote it out on a piece of paper and handed it to him. He nodded his head approvingly. The prisoner repeated his question in the same cold tone: “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

She opened the file and began to search for the Post-it notes she had scattered through it the previous evening to remind her of actual discrepancies between the written reports and the tapes.

The main features of his short life were clearly recorded by many different hands in the file. His father was a famous carpet dealer in Casablanca and frequently sent him to Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan. On his last trip he had fallen in love with a beautiful young woman, who was studying in Islamabad and had not returned home. He had married her and remained in Pakistan because her family stipulated that. He stopped working for his father and moved to Peshawar, which is near Afghanistan. There he could obtain cheap, excellent carpets from Pakistani and Afghan villages. So he began to supply carpets directly to shops in Morocco, Spain, and France.

On September 15, 2001, he went to deliver a pickup of carpets donated by wealthy people in Peshawar in order to supply some mosques in poor villages near the city of Gardez, Afghanistan. These had been rebuilt following an air raid by foreign air forces that had totally destroyed them. The donors had asked him to deliver the carpets to the religious scholar Hamidullah Kabiri in a region at the border between the two countries. He was going to send Muzaffar, his brother-in-law, and Rawi, a friend who worked with him, but Muzaffar had convinced him to come along, saying, “You’ve never watched snowflakes caress your face, seen snow cover all the natural world, plains, boulders, valleys, hills, and mountains. That’s the most beautiful sight you’ll ever witness. You’ll remember it as long as you live. It won’t take us more than a day and will make for a good trip and good business.”

They climbed into his small, new, white Nissan sedan. They made it to within a hundred meters of the curving, twisting pass, which coils around on itself like a viper from the beginning of the Hindu Kush Mountains to the Afghan border. The pass only allows for one vehicle to traverse it at a time. Vehicles need to stop beside the mountain if the driver sees another vehicle coming, otherwise one of them will fall into a deep abyss from which there is no escape. Just then they heard the loud honking of a large truck moving at top speed. The driver wanted to traverse the pass before them. The major error occurred at this juncture: they made room for it to pass. The cab of the truck was blue, but the remainder of its frame was a dark rust color. But it missed its chance to enter the pass, and the carpet pickup got into the pass before the other truck. So that truck was forced to follow it. Thus Ahmad’s vehicle was separated from that of the carpet pickup, through no fault of their own. Then what? The pass would end shortly, where the Nissan would catch up to the carpet pickup, and they would travel on together. When the rusty truck was only ten meters from the pass, though, helicopters attacked it, raining down bombs. The truck, which was in front of them, exploded, becoming a giant fireball that seemed to want to engulf all of existence. It appeared to have been filled with explosives that shredded the truck’s metal, casting shrapnel in every direction, sowing fire and death directly in front of them. The tongues of fire and plumes of smoke reached to the stars, setting space itself ablaze.

The next thing Ahmad knew he was alone in a hospital. Where was Muzaffar? Where was Rawi? Where was the carpet pickup? Where was his Nissan sedan? He had no idea. No one spoke to him; there was a heavily armed guard at the door of his room. No one would answer his questions. No one reported his condition to his wife, her father, her brothers, her sisters, or his family. He was cut off from the whole world. Armed men came and arrested him before he had recovered. One band of men received him and then handed him over to another. Then it was a third, then a fourth, then, then, then, until he ended up here with thousands of other prisoners and the interrogations, which had yet to end, commenced.

The prisoner’s mouth opened, and he repeated in a lovely, sweet voice, as if from another world, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

He remembered everything that had happened to him before the attacks of the helicopters and after his departure from the hospital. He remembered everything and described it with the accuracy of a fine camera, even the colors of his series of prison uniforms, which had been blue, then gray, then khaki, and finally red before it was spotted, before it was blue again, then, then, then, and so on. He remembered the food, the hunger, the torture, beatings, and curses. He remembered his companions in all the prison cells. He hadn’t forgotten a single one of them, having registered all of them in the whorls of his brain. In his many statements he mentioned how many planes he had boarded with hands, feet, eyes, ears, and mouth bound, swathed, and gagged. He even estimated how many hours he had flown! He described how he had been cuffed, kicked, and tortured. This cinematic sequence began with the explosions of the truck and ended with his landing at the penal colony of the green lizards. From his statements and his answers, he appeared to be one of the smartest individuals she had ever encountered, if not by far the smartest. He anticipated that, thanks to his intelligence, he would realize all his objectives in life. Over a period of sixteen months his statement had been repeated dozens of times. The content remained the same and the words were virtually unchanged. Why all this stupidity: the interrogation, examination, and questioning? The case was clear as daylight.

Imagining that he was her brother, Zaynab asked him calmly, “Ahmad, why does it matter to you how many children I have?”

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal dirri ma‘ak?”

The general asked, “What did he say?”

“The same sentence without any change: ‘Iraqi woman, how many children do you have?’”

“Does he know you’re Iraqi?”

“Yes, from the first word I spoke.”

“How?”

“From my accent.”

The general became furious and shouted, “I told you he’s vicious. This Ahmad has exhausted us. Beat him. Motherfucker, shit! Beat him. He deserves to die; he won’t cooperate.”

She could have wept. She said in almost a moan, “I can’t strike him. Why don’t you?”

The general yelled with the same insanity that had seized hold of him, “Look at him. He’s very weak, perhaps only eighty pounds; he weighs no more than a child—less than ninety pounds. If I hit him a single time, he’ll die at once, and I’ll be accused of killing a man. But he’s nothing but vermin, an animal. You’re a woman. You don’t hit as hard.”

The prisoner’s mouth opened, and he repeated in a lovely, sweet voice, as if from another world, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

The general yelled as he looked at the stocky soldier, “Get the gizmo. Let him taste the reward for his reckless behavior.”

He disappeared quickly into one of the rooms. Suddenly she felt the temperature in the trailer increase till it became hard to breathe. More than one sweat stain appeared on the prisoner’s shirt, and its red color acquired maroon spots. Then she was stunned to find sweat pouring from her face and her clothes sticking to her body, especially beneath her armpits and at her waist. She felt perspiration inflaming the wounds between her thighs. She cast a glance at the general and called anxiously, “Isn’t there any air-conditioning here?”

The general turned to his aide and shouted, “Turn on the air-conditioning.”

A chilly breeze circulated through the room, and she felt refreshed. Meanwhile the soldier returned with a short, thick, black stick, a small box with a red cross on it, and a spongelike gadget with a cord that he plugged into a wall outlet. Near the prisoner’s belly, he sat on his butt and brought his knees to his chest. This stocky soldier’s clothes revealed his bulging muscles. His skin was ruddy, and his hair black, although he was almost bald. His eyes bulged out till they were practically on the same plane with his eyebrows, and his nose was short and flat. After placing the stick and the first aid kit on the floor, he tried to raise Ahmad’s head. The prisoner, however, tensed his body to prevent him. All the same, the soldier had no difficulty in lifting the prisoner’s head. Then he wrapped it, leaving only his nostrils visible. The soldier next pulled up his shirt, revealing a milk-white belly as skinny and concave as the midriff of a child of ten. The shallow belly button reminded Zaynab of her brother’s, and she was close to tears. Gaining control of herself, she riveted her eyes on the soldier.

The soldier untied the waistband of the prisoner’s red uniform pants, drew them down, letting the long white underclothes show, and placed both hands around the prisoner’s hips, raising him a little. Then he put his right hand under the prisoner’s buttocks and pulled his underpants down with his left hand while the prisoner jerked futilely right and left. The upper portion of his hairy thighs was visible as well as part of his left buttock. Then the soldier dropped Ahmad’s butt back on the floor in its original position.

The prisoner’s movements became increasingly agitated and nervous as the soldier pulled all his clothing, from each side, down to his knees. The prisoner released a muffled sound like a hiss, and all eyes were drawn to the thick, black pubic hair rising a few centimeters from pure brown skin, filling the void. The soldier’s thick fingers reached down and pulled up the prisoner’s penis, which began to tremble and shake involuntarily. Zaynab wondered whether he had been subjected to this treatment before. Grasping the penis between his thumb and just two fingers, the soldier yanked it up so forcefully that the prisoner moaned, but the fabric swaddling his face made his voice sound dry and choked. His penis resembled a flimsy rope stretched fifteen centimeters long. The soldier took the sponge machine, opened the sides, which were like clamps that were hollowed out in the middle, and attached it to the penis as the prisoner began shaking again. The soldier wrapped the machine with a black elastic strip fastened to it and dropped it onto the patch of thick, coal-black pubic hair. Then he pressed the switch on the electric cord, which was plugged into the wall. The apparatus began to move, emitting a loud whistling sound. It rose and fell and moved right and left. Ahmad’s body shook along with it, trembling as if he were part of the gadget. His saliva-soaked gag emerged from his mouth along with a sound that was hoarse, strangled, and like a rattle. It resembled a scratchy gasp from a deep pit. Meanwhile the soldier was watching as the hands of the clock attached to the apparatus marched resolutely toward the left.

Zaynab rose. The world was revolving around her. Her head had doubled in size and internal pressure. Her eyes were bulging out, involuntarily. Suddenly sensing she was about to throw up, she quickly retreated behind the general. Her stomach backed up, and she vomited some liquid on the floor with an audible explosion. She spat and closed her eyes. My God! Where have I landed myself? Noticing a chair beside the door, she dropped onto it and put her head in her hands as tears streamed out. She felt the dapper blond soldier touch her shoulder. He handed her a water bottle, and she took a sip. Then she poured some water in her right hand and washed her face. She sighed deeply and regained control of herself. The general looked at her and motioned for her to come back. She returned to her original position. The prisoner was still going crazy from the vibration of the powerful apparatus and perhaps from atrocious pain. How long do you suppose he will hold out?

When the hand of the clock reached zero, the general shouted, “That’s enough. Begin.”

The soldier opened the machine’s two wings and grasped the penis again to test it. It had become a little firmer and was the thickness of his thumb; the color had changed from white to a blackish red. The prisoner was still shaking violently. The soldier seized the glans of his penis with the fingers of his left hand and pulled it up again. With his right hand he grasped the short, black stick. Then, in the wink of an eye, he struck a lightning blow to the penis, causing it to swing from right to left while blood flowed from the place the blow had landed. The prisoner was shaking and trembling wildly, while huffing and puffing like a freshly slaughtered bull. His gag was soaked with saliva. The soldier hit again numerous times until blood gushed from the penis in more than one location. Actually, blood splattered in various spots with some drops landing on the bald soldier’s face and others staining his trousers. The blood drops formed an ellipse on the prisoner’s body and the floor. Zaynab groaned and closed her eyes. Once more, her tears betrayed her.

She did not know when the beating ended, but the prisoner’s body was still moving, rising and falling, and his groan had become shriller. His head jerked right and left. From beneath the gag, the soft chattering of his teeth was audible.

The soldier turned to ask the general, “Should we attack again?”

Gazing at the blood that soaked the prisoner’s white underwear, red pants, and the floor, the general replied, “No, that’s enough.”

So the soldier reached for the first aid box and sprinkled on the penis—from a bottle like a perfume flask—a blushy white liquid that covered it from every side. This seemed to hurt the prisoner, and he began to groan loudly. Then the soldier wrapped the penis with white gauze, which soon developed red blossoms. When he finished, he carefully wiped the blood from the prisoner’s belly button, brown skin, pubic hair, and groin area. Then he sprinkled that entire region with a green liquid from another bottle. He continued wiping up the blood until the body was clean. Then he pulled the bloodstained underwear back up and retied the waistband of the red pants. The prisoner’s groans and huffing were so powerful that he seemed to want to die. She hoped in her heart of hearts that he would not, anticipating that it would take him an entire day to regain a normal state of consciousness. The soldier, however, removed the gag. From the drops of blood on the prisoner’s lower lip, she deduced that he must have bit his lip because of his intense pain. The soldier was engrossed in his work, which he undertook deliberately and with professional skill. Taking out a yellow bottle, he held it close to Ahmad’s face. When he pressed the top, a thick drizzle came out, emitting a strong, sour smell that made Ahmad move his head right and left before it fell back into its original position. He began breathing normally again after about a minute.

Zaynab turned her face to the left to wipe away her tears and then looked at the prisoner. She herself had been sexually violated in a similar way after drugs had rendered her unconscious to what they were doing to her. The first day she arrived here, the women soldiers had invited her to go to the bar. When she told them she didn’t drink, one asked, “Not even orange juice?”

She laughed and said, “No, I do drink that.”

“So come with us.”

At the bar, which was drenched with light, cigarette smoke, loud, ear-popping music, and wild dance moves, she didn’t find any orange juice, but the Coca-Cola seemed delicious. The next day she found herself in the hospital and didn’t know what had happened to her. Her body wouldn’t obey her; she couldn’t lean forward. She couldn’t stand on her own two feet. Her underwear was torn, and her insides felt torn up too. Fire burned her wounds when she urinated, and she bled when she tried to defecate; the pain was unbearable.

She did not understand the nurse’s knowing glances, silent mouth, and enigmatic smile. Her eyes had been the most eloquent. Some female companions who had flown with her from Detroit on the same cargo plane each spent a few minutes with her, weeping feverishly. Why? She didn’t know. They left. She asked each of them, “Has anything like this happened to you?” But there was no reply. Just tears. Had what happened to her happened to other women? She did not understand. Perhaps she never would.

The next afternoon, General David had visited her himself. When she complained about what had happened to her, he took a picture from his pocket. She stared at it. A huge officer she had never seen was carrying her in his arms like a child, without any objection from her, and her eyes were closed. The general asked, “Is this you in the picture? No one could carry you in his arms without your consent. Who could doubt that?”

So everything was anticipated, and calculable. That was a conclusion she had never imagined. Her tears started to flow, and she remained silent.

It was a photo of her. All she could remember was chatting with her female companions and drinking Coca-Cola. That was all her brain could offer. So when had this giant arrived? How had the picture been staged?

The general surprised her by asking, “What is your annual salary according to your contract?”

She assumed he wanted to change the topic, and tears came to her eyes. He glared at her, and she replied, “Two hundred ten thousand dollars.”

“A high school teacher doesn’t make more than thirty-five thousand dollars a year. Your salary is six times more than a teacher’s. Everything has a price. Isn’t that so?”

So everything was anticipated, and calculable. That was a conclusion she had never imagined. Her tears started to flow, and she remained silent.

The general added, “In your papers you mention that your daughter needs an important bone operation.”

She nodded her head in confirmation.

“She will have it, thanks to your sacrifice.”

Her calamity was too great to be washed away with tears. She was a tasty morsel that had landed between a leopard’s claws. What could she do? If they had taken this photo of her, no doubt they had taken other pictures of her in much more compromising positions. She remembered what the general had said about the lizards. They seemed to have allowed the lizards to roam freely to serve as a realistic symbol for everyone working there. Their bite left a tattoo-like mark that would last a lifetime.

“Question him.”

The general’s command roused her from her misfortunes. When she looked at the prisoner, she noticed that tears were flowing from his eyes, which were covered by a damp band. She conjectured that these were involuntary tears, because he appeared in control of his nerves as he was previously.

She called to him as gently as if speaking to her brother. “Ahmad? Do you feel better now?”

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

The general asked, “Did he repeat that same sentence?”

“Yes.”

“What a rogue!”

She turned to face the general. “Why shouldn’t I answer him? What’s wrong with that? Let him grow accustomed to me.”

The general yelled forcefully, “No, no, no! We’re questioning him, not the other way round. What does he amount to? He’s shit. Shit!” He paused for a moment and then said, “Give this motherfucker a choice. He confesses now or we put his prick back in the machine till it’s destroyed and he becomes a eunuch.”

She drew closer to his ear. “Darling Ahmad, you know English, don’t you? You heard the general. You know what he intends to do. He’ll kill you. What do you say?”

As if he hadn’t just undergone this ordeal and had never heard the general or listened to her, he repeated as resolutely and calmly as before, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

“Ahmad, don’t be a fool. You’re smart. Think of your future. You’re young. They will kill you.”

She imagined that he smiled.

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

He sang this sentence again in a beautiful, powerful voice. She totally lost control of herself and began to weep loudly. She screamed, “They’ll kill you! You’ll be done for. They’ll rob you of your manhood. Wake up, Dummy!”

When he wouldn’t keep still, she hit his chest with both hands as she screamed, “That’s enough!”

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

“Enough!”

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

“Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough. Enough.”

“Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

Her hands fell on the left side of his chest. She screamed and beat him time after time with increasing violence. The pains in her midriff tore into her savagely as their flame seared her. She was weeping even more wildly, and the pitch of her voice rose with the increasing fury of the movement of her hand, which was accompanied by her sobs. Not realizing what she was doing, she continued beating him as she repeated loudly, “Enough!”

He punctuated her yells with the refrain, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

Eventually his voice died away and he was silent. His lips stopped moving and nothing emerged from his mouth. Only her screaming and the drumming of her hands on his chest continued. “Enough! Enough! Enough!” Then she realized that she was the sole player left on the field. She stopped and stared at him. He wasn’t moving or breathing. What a frail body! She put her ear to his chest as her tears streamed onto his red clothing. She couldn’t hear any heartbeat. It was a still body, as quiet as a stone. She began to weep loudly. The general tugged on her right shoulder. “It’s not your fault. Don’t weep. This is the end he deserves.”

He looked at his aide. “Call the doctor to take a look at him.”

The general left and she followed. Her footsteps were tentative and feeble. She barely avoided stepping on the lizards, even though these green reptiles moved to make room for them. She was sobbing and trembling. Her mind and senses were with the rigid prisoner back inside, and she could still hear him repeat, “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?” Deep in her heart of hearts she refused to believe that he had died. What possible reason could he have had for insisting on learning how many children she had? It was lunchtime, but she had no appetite and stayed in her little office, where she sat rigidly at the computer, her thoughts scattered.

Soon afterward the general summoned her and placed some papers before her to sign. These declared that the prisoner Ahmad Attawil had killed himself by refusing food. “Known for his rebelliousness and arrogance, he refused to eat dozens of times. He is the only prisoner who continued his hunger strike for eight weeks. He was so stubborn that he chose to kill himself to embarrass the camp’s management, despite the excellent treatment that he and the other detainees have been accorded in keeping with international standards of human rights and responsible legal conduct.”

Pointing to a pile of stuff in front of him, the general said, “This is everything he had. You are a witness.”

She gazed at the pile: a fine man’s watch with a silver band, a gold ring, an insurance policy issued by a Pakistani firm for a Nissan Sunny sedan, and a photo of Ahmad. Her heart pounded, and she remembered that she had yearned to see his features. Here was his photo. She had not seen him alive; so let her stare at his picture now that he was dead. Oh, how handsome he was! More handsome than her brother—a broad forehead topped by an arch of coal-black hair, dark but as handsome as the moon. Beside him was a very beautiful bride, no older than eighteen. She wore a splendid white wedding gown ornamented with Pakistani finery. Finally, there was a Pakistani driver’s license with his picture in color. She wasn’t able to look at the photo any longer and turned her head away. Perhaps he would come back to life and criticize her again. His echoing words pierced their way through existence: “Aaa, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

Here was another photo, this one of a six-month-old girl who resembled her mother. Her wide, sparkling eyes sent the viewer a bright, expressive look. The general looked at his blond aide and said, “Come sign.”

The soldier signed and departed. Zaynab was about to sign when the telephone rang and the general turned to answer it. She reached out her hand and picked up the picture of the beautiful child. What ravishing eyes she has! She must be two by now. That was how old her daughter, Niran, was. Was this why he had asked, “Lady, how many children do you have?” Why had he insisted on adding the word “Iraqi” to the question? Why had he repeated the question?

By the time the general had finished talking, she had signed. Then the general resumed putting Ahmad’s personal effects in a nylon sack. On a piece of paper he wrote, “Ahmad Attawil al-Maghribi. Deliver the contents of this bag to anyone deemed by judicial authorities to be his heir.”

He signed beside the signatures of the two witnesses and then printed his name and the day’s date: May 4, 2003.

The general put the bag in the drawer of a gray metal cabinet to his right. Then he looked at Zaynab and said calmly, “I’ll send for you after lunch and we’ll question another prisoner.”

As she departed, the child’s glances shot fiery arrows that set her ablaze in the confines of a room where echoes of her father’s voice collided with each other as he sang, “Aaa Lalla, Lalla al-Iraqiya, ashhal min dirri ma‘ak?”

Translation from the Arabic

By William M. Hutchins

This piece is one of WLT's 2012 Pushcart Prize nominations.