Editor’s Note

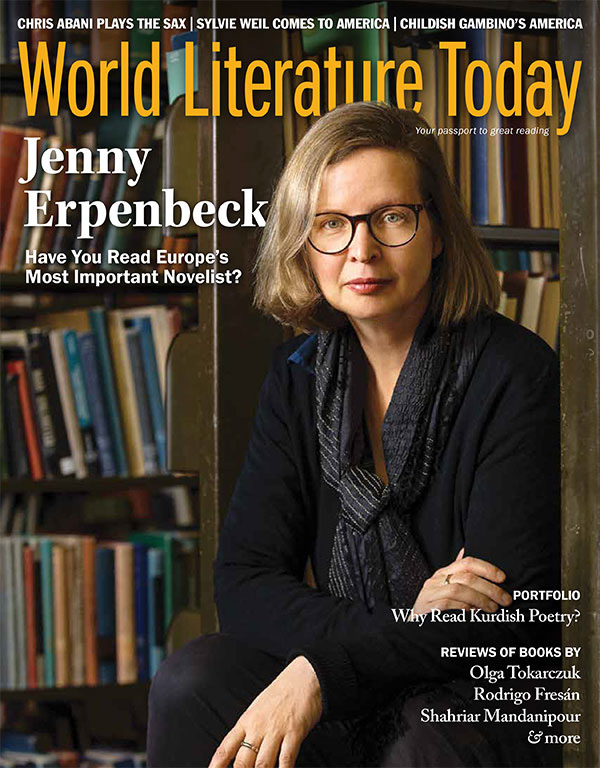

How does one become a writer? For German novelist Jenny Erpenbeck, it was less epiphany than the gradual accretion of circumstance and intention. Here is what she told Haaretz in 2011: “I turned into a writer when I played among the ruins left by the war in the heart of Berlin; when the streets where I grew up became a giant construction site; when my mother allowed me to skip school to go ice-skating; when my father took me to excavations of walled fortresses; when I went dancing; when I fell in love; when I had my hair cut; when my neighbors had too much to drink; when one of my grandmothers told me about the camps in Siberia and the other one about migrating; when I mixed bookbinders’ glue; when I read whenever I had time. After I finished my studies, I became an opera director and a baker’s assistant. That’s when I decided to write my first long text.”

The ruins of postwar Berlin that Erpenbeck played among included not only the devastations of World War II but those of Cold War–era East Berlin in the German Democratic Republic of the 1970s and ’80s (see “After the Wall Fell,” WLT, Nov. 2014). In an essay for the Paris Review, beautifully translated by Susan Bernofsky, Erpenbeck describes the infamous Berlin Wall not so much as a barrier to physical freedom as a blank slate for the imagination: “For our Sunday walks, my parents would bring me to the end of Leipziger Strasse, to the area right in front of the Wall, where it was as quiet as a village. There was smooth prewar asphalt perfect for roller-skating, and the final stop on the bus line, no through traffic beyond. This was where the world came to an end. For a child, what could be better than growing up at the end of the world?”

Erpenbeck’s spirited inhabitation of that seeming dead end on Leipziger Strasse morphed into a fascination with theater and music in college, eventually leading to those key apprenticeships: bookbinder, baker’s assistant, opera director. Whether it was mixing glue, kneading dough, or staging arias that precipitated the shift, one day the writer’s imagination clicked in her mind. Inheriting her parents’ and grandparents’ own love of the written word as embodied in their lifework as publishers, scientists, philosophers, poets, and translators, Erpenbeck began writing a novella and the stories that helped her burst onto the German literary scene in the early 2000s, followed by the major novels and countless literary prizes that eventually led the Guardian to describe her in 2017 as “Europe’s outstanding literary seer.”

Amidst all the fame surrounding her work, Erpenbeck remains interested in “the silence of things and spaces” and—shuttling between the personal and the historical, the visible and the invisible, chance and destiny—often thinks about “how time is tied up in objects and places” (Aēsop). In that same Paris Review essay, she writes: “For me, an empty space did not bear witness to a lack. It was a place that had been either abandoned or declared off-limits by the grown-ups, and therefore, in my imagination, it was a place that belonged entirely to me. . . . An empty space is a place for questions, not answers. What we don’t know is infinite.”

Even as the world came to an end at the foot of the Berlin Wall, a young girl walking with her parents imagined time and space untethered from the dead ends of history and the mere coordinates of geography. As readers, how fortunate we are to accompany writers into such imagined worlds.

Daniel Simon

Special thanks to Dr. Kelvin Droegemeier, OU’s Vice President for Research, for sponsoring a grant from the Norman Campus Research Council Faculty Investment Program in support of the 2018 Puterbaugh Festival.