Reinventing and Reimagining the World: A Tribute to Marilyn Nelson

Hayan Charara, a poet, editor, essayist, and children’s book author, nominated Marilyn Nelson for the 2017 NSK Prize. The following text is adapted and abridged from his nominating statement.

In 2012 Marilyn Nelson, currently a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, received one of the most distinguished honors conferred on an American poet, the Frost Medal, the highest award presented by the Poetry Society of America. Previous recipients include Wallace Stevens, Allen Ginsberg, Marianne Moore, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery, Sonia Sanchez, Galway Kinnell, and Lucille Clifton. To be in such company is impressive, to say the least. But to quote Marilyn Nelson’s Frost Medal acceptance speech: “Our achievement can’t be determined by book sales or awards; what we achieve now won’t be recognized until later.” She is right, of course. So what does achievement look like, then? Again, I refer to Nelson’s own words:

Will people be able to look back and say that our poems helped halt the degradation of the language? Will they say our poems helped undo some of the desecration of ideas, values, and institutions once held universally sacred? Did our poems remind people to value truth, faith, each other, themselves, and the planet? Did they teach Americans to be wiser stewards? Did they help Americans rediscover America’s best hope for itself?

The long and distinguished list of Frost Medal recipients contains one poet after another whose poems have indeed accomplished some or most of the above. And, without a doubt—though she may not herself admit it—so, too, has Marilyn Nelson’s work. Written simultaneously for children and adults, her poems aim to change lives, ideas, and language for the better and for the long run.

I point out Nelson’s distinguished reputation because the work for which she has many times been recognized as a significant voice in American poetics happens also to be work categorized as either young-adult literature or children’s literature. Nelson is the “rare bird”—the poet accessible to adults (an unusual feat over the past century or more) and to younger readers. Perhaps more significantly, she often reaches both audiences with the same set of poems. While her work has for a long time (decades now) made itself available both to young and adult readers, Nelson made the decision to publish almost exclusively for younger readers a decade ago. Mind you, adults still read her work; her poems still appear in prestigious and hard-to-publish-in literary journals, but she prefers the YA designation, or some version of it, when publishing her books, and for good reason. More than ever American poetry needs voices that pull readers in and open up imaginations instead of pushing those readers away and shutting their imaginations down.

Nelson understands that, in America at least, every year, fewer and fewer people read poetry. To any poet, this is a fact astounding and sobering. For Nelson—and she is not alone in this assessment—something must have gone wrong with American poetry. Why, she wonders, aren’t poems knocking the heads off more and more readers? Every poet has a story about such an experience. Usually, it occurs at a young age. With Nelson, it was as a teen, and with James Dickey’s poem “The Sheep Child.” The point is: Nelson wants to create poems that do this for younger readers because she understands, from experience, from stories others have been telling generation after generation, that poems, and creative works in general, carry with them the capacity to change lives, to create in readers unforgettable experiences and emotions, and to set down the foundation for a lifetime of such experiences. She wants her readers, at a young age, to fall in love, deeply in love, with the written word, so that this love (which will transform into other emotions and other impulses) will remain with them into adulthood and throughout the rest of their lives.

The decision to publish her so-called adult poems for young readers began with Carver: A Life in Poems, a Newbery Honor Book, Coretta Scott King Honor Book, Boston Globe–Horn Book Award winner, Flora Stieglitz Straus Award winner, and a finalist for the National Book Award. The poems create a rich, revealing, and dynamic portrait of George Washington Carver, the famous African American inventor (and botanist, painter, musician, and teacher). The language she uses is simple but not simplistic. The ideas and experiences can be complex and weighty, but—as with her other works—Nelson handles them with care and deliberateness, not lessening or lightening the depth of her subjects but transforming them so that they rise to the occasion. And the occasion, so often in her books: writing about difficult histories, and difficult subjects, like race, identity, struggle, sorrow, and loss, both individual and collective, in such a way as to make them understandable, enjoyable, and memorable. An example—one of many—is the poem “Friends in the Klan,” which is about Carver, now a doctor at a new “Negroes only” hospital in Tuskegee, recognizing the handwriting of a fellow doctor (a white man) on a note left by the KKK protesting the new hospital.

If you want to stay alive

be away Tuesday. Unsigned. But a

familiar hand.

The Professor stayed. And he prayed

for his friend in the Klan.

Beneath the poem is a photograph of three KKK members, with the caption “Parade of the KKK” and a note: “1923. Carver receives the Spingarn Medal for Distinguished Service, the first of many such honors.”

What Nelson does here, she does elsewhere and often: she does not write what some call “activist” or “political” poetry, labels often used to denote “bad,” propagandist poetry or else apologist poems for injustice; rather, the poem operates in the space where the personal and universal come together, where dignity is given prominence, and where both the victim and victimizer are attended to with humanity—neither is stripped of what makes them human, regardless of their faults. In this case, the KKK doctor, who is also a friend, is the focus of sympathy, perhaps even empathy. While the poem may represent historical fact rendered into poetry, the poem itself enacts that which “the Professor” embodies: the poem praises and condemns (actions, but not people) while also being unafraid—in the case of Carver and so many African Americans, unafraid to stand against racism and threats of violence; in the case of the poem, unafraid to teach this history, to treat it not with anger, resentment, or righteousness but with dignity and humanity. And while the poems in the book address events nearly a century old, they are certainly relevant today. Threats and acts of violence continue to plague American life, especially the lives of African Americans, especially the young.

Nelson’s poems aim to change lives, ideas, and language for the better and for the long run.

Through the use of metaphor, line breaks, unusual and unexpected juxtapositions, and an insistence on making the ordinary extraordinary, poetry participates, perhaps more than any other genre, in reinventing and reimagining the world. I mean to say, on one hand, something quite simple: that a person can look at a poem and know it immediately to be so; the same can’t necessarily be said of a prose piece—it may be an essay, or a short story, a memoir, a letter, and so on; and in poetry, the usual conventions of grammar and style do not apply; the strange and unusual, the entirely new, and the not-entirely-understood (but perhaps only sensed or felt) are acceptable, even praised—not so for most other genres. All of which is to say, on the other hand, that poetry participates in something quite complicated and difficult to nail down. The power of poetry is in its nature, its conventions: it seeks to unsettle what we may think to be settled; it disrupts the usual order or expectations of things; it forces us to see the world—rendered into words and images—in ways that we never thought the world existed, or else we simply overlooked. Again and again, for more than thirty years, Marilyn Nelson’s poems keep doing these things. With lyrical or narrative poetry, a novel in verse, or a picture book, her writings awaken us to the possibilities of language, especially in its capacity to shape our understanding of history, of the places we call home, the people we call friends, family, and even enemy, and maybe most importantly, her poems make evident the capacity for poetry to bring everything to a stop. Anyone who has ever heard a great poet read knows this experience: the poem ends, and there is dead silence, but the room is filled with a palpable energy or tension. If only for a moment—and sometimes, that is all we need—everything comes to a halt, and we stand face to face with what matters most, or what we did not realize, or what we knew all along but needed someone else to bring up.

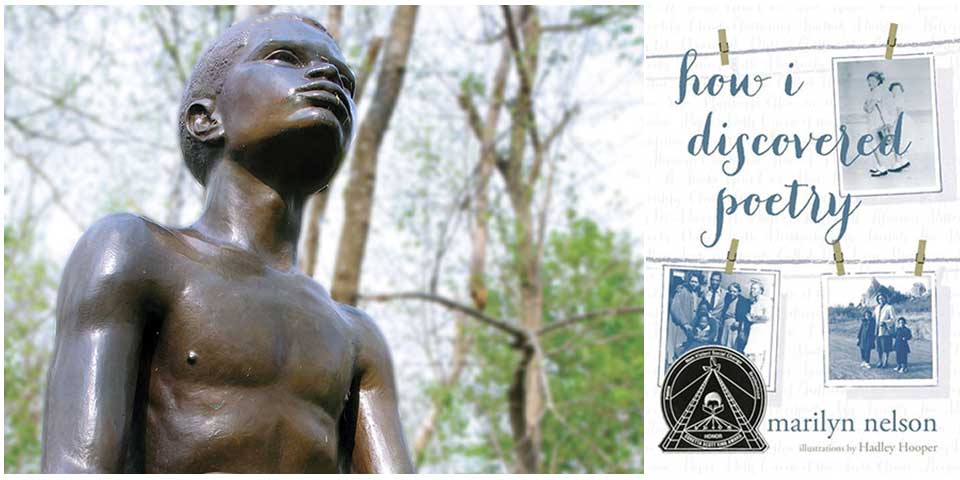

One of Nelson’s most beloved books is How I Discovered Poetry, and the title poem brings back to life such an experience, presumably one the poet herself had as a young reader. In the poem, a teacher, Mrs. Purdy, reads to a “white class,” and all the students zone out, looking forward to the 3:15 bell that will send them home and end the boredom of someone reading to them—all except for the young Nelson, the only black child in the classroom.

Mrs. Purdy and I wandered lonely as clouds borne

by a breeze off Mount Parnassus. She must have seen

the darkest eyes in the room brim: The next day

she gave me a poem she’d chosen especially for me

to read to the all-except-for-me white class.

She smiled when she told me to read it, smiled harder,

said oh yes I could. She smiled harder and harder

until I stood and opened my mouth to banjo-playing

darkies, pickaninnies, disses and dats. When I finished,

my classmates stared at the floor. We walked silent

to the buses, awed by the power of words.

How does a person handle such devastation, betrayal, and humiliation? It is impossible for the irony of this life-altering experience to be lost on anyone—certainly not the students in the class, who looked at the floor in embarrassment or shame, and obviously not on the child, whose awe of poetry, of words and reading, could have had the effect of wrecking and ruining her love of language and learning. Instead, she recognizes that, like gods and nature, words are awesome—impressive, daunting, inspiring great fear and great admiration—and for the rest of her life, up to the present, she invites young readers to share in the awe, so their lives may be altered ultimately for the better. She also imparts another message worth holding onto for a lifetime: “the power of words” can destroy as much as it can create. In this way, the poet acknowledges the responsibility of the poet to the reader; it is a responsibility not very different from a teacher to a student. It goes without saying, some poets—and some teachers—are better than others.

Through the use of metaphor, line breaks, unusual and unexpected juxtapositions, and an insistence on making the ordinary extraordinary, poetry participates, perhaps more than any other genre, in reinventing and reimagining the world.

In the long run—fifty, seventy-five years from now, longer—the awards and honors Marilyn Nelson has received will not necessarily determine what she has accomplished. But I can say this: I knew and read her poems long before I realized the awards given to them, and when I finally realized just how honored the work had been, it was no surprise at all. What will triumph ultimately is not this or that award, or a shiny gold or silver sticker on the cover of a book. Instead, the power of language will last; its ability to endure and to overcome will outlast us all, and I am certain that Nelson’s work will also make its way there.

University of Houston